Chitrasena’s Mudra Natya: Embodying the form

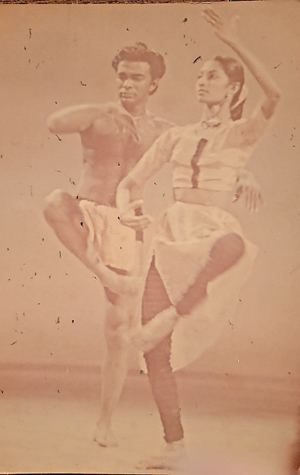

1957: Chitrasena and Vajira in Sama Vijaya

January 26th, 2021 marks the 100th birth anniversary of the traditional dance maestro Chitrasena. While he had a far-reaching cultural impact, including in representing the tri-traditional dance forms viewed as indigenous to the island (Kandyan, Low Country and Sabaragamuwa) on stage, this article focuses on one element, the mudra natya also referred to as the Sinhala ballet.

In 1957, Chitrasena was invited to perform at the World Festival of Youth and Students, held from July 28th to August 11th in Moscow. This was his first international tour. Chitrasena and other Sri Lankan dancers were to perform the mudra natya Sama Vijaya or Triumph of Peace. The production was commissioned by the Ceylon Peace Council, an affiliate of the World Peace Council, which was a global peace movement backed by the Soviet Government. Prior to its presentation in Moscow, the ballet premiered at the Ladies’ College Hall in Colombo on June 13th that same year. A local review of the production in a newspaper of the time, The Tribune, drew attention to the novelty of the choreography:

“It was a show which was different from anything I had seen before in Ceylon. The dance technique was Kandyan moulded by the influence of Santiniketan, but that was not the most important thing about the show. It was not an exposition of dance forms. The Kandyan dance forms and the reapers dance from Sinhalese folk art were utilised with great artistic restraint to fit into the theme.”

A brief, three-minute segment of the performance in Moscow remains publicly accessible, providing us with a snapshot of the production. As captured in the video, Chitrasena and Vajira – his partner in dance and life -portray mankind in a duet of contrasting styles. Chitrasena’s undulating and expressive hand gestures stand out, while he approximates the overall movement of the step yet gives weight to the dance. Vajira draws attention to the full line of each step and is more delicate in how she traces the movement.

The short ballet was a collaboration with other leading artists including Vasanthakumar and Panibharatha, who portrayed the elements. In addition to the Kandyan drum, vocals and violin were used to provide an emotive soundtrack for the tragic ballet. The overall narrative for the short piece had been conceived by Teja Gunawardena, who worked with Chitrasena to develop the plot of the ballet. Sama Vijaya was an overtly political piece portraying a nuclear Armageddon and was an indictment of the nuclear arms race. That this protest piece was showcased in Moscow at that time is remarkable. It was the height of the Cold War and the two superpowers – the USSR and USA – were pitted against each other in various parts of the globe and in space, as they flexed their muscles and triggered a series of crises resulting from actions such as the declaration of the Eisenhower Doctrine and the launching of Sputnik, thereby intensifying the nuclear arms race.

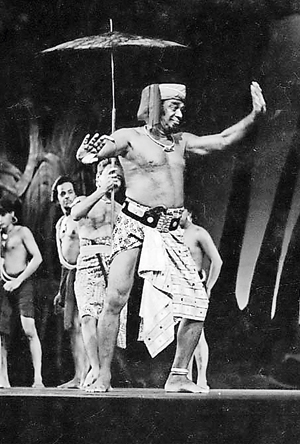

Chitrasena as Mandadi Raala in ‘Karadiya’

The confidence with which Chitrasena presented this and other ballets, or mudra natya as they are referred to in Sinhala, and the positive response with which they were received in the USSR and other centres of classical dance, demonstrated how successful he was in creating productions in a format that was still novel to the Sri Lankan stage. Chitrasena played an influential role in the emergence of the Sinhala ballet in the period around independence. While the identity of the first mudra natya is contested, Chitrasena was clearly at the helm of a set of leading performing artists, who were experimenting with this medium.

Its precursor was the dance drama that relied on a variety of narrative tools and proved popular among theatre practitioners and audiences in the pre-independence era. The distinct feature of mudra natya was the use of dance as a primary narrative tool. As the tri-traditional dance forms of the island, despite the emotions they could evoke, had limited narrative scope, this set of artists developed a new movement language. In the case of Chitrasena, while drawing elements from both Western and Eastern (primarily Indian) narrative dance productions, such as to devise scenes, he used Kandyan and Low Country dance forms as the foundation for the movement. It is important to note that in the different productions staged by the Chitrasena Dance Company, he explicitly sought to make a distinction between his mudra natya and his work that was devoted to representing and celebrating the tri-traditional dance forms.

Although a relatively recent phenomenon, the Sinhala ballet or mudra natya is viewed as a key component of modern Sri Lankan art and culture. It represents two inter-linked strands critical to the revival of culture around independence. While there was a concerted effort to ‘re-discover’ desheeya (indigenous) art forms, there was also a desire to innovate and respond to the contemporary world, thereby asserting the distinct voice and identity of a decolonised and independent culture, people(s) and state. It is in this highly-charged context that Chitrasena created and performed. In highlighting the contribution that Chitrasena made, the Sinhala paper Peramuna (1949) talks of Nala Damayanthi giving national culture a new lease of life. Chitrasena’s work was thus absorbed into the narrative that sought to present mudra natya and the tri-traditional dances as integral components of Sri Lankan culture during the decades following independence, which saw tremendous activity and growth in the fields of visual arts, music, literature, theatre, film and dance.

Beyond his role in the development of this genre of dance theatre, Chitrasena’s full length ballets are considered to be the embodiment of the mudra natya. As the cultural commentator and critic Neville Weereratne (2003) noted: “When Chitrasena opened the doors of the Lionel Wendt Theatre in 1961 with Karadiya, he did something quite wonderful. He created a dance-theatre unique to the traditions of Sri Lanka, and indeed, to the experience of many parts of the world… Karadiya was the first complete ballet, combining elements of the dance as known and recognisably Sri Lankan in character and a highly articulate language of mime and gesture, wrought and subject to the needs of the narrative.”

Even while some of his contemporaries also experimented with the form and staged their own productions, Chitrasena’s productions had a singular and distinctive impact on audiences. As Dr. Marianne Nurnberger’s documents in her publication, Dance is the Language of the Gods (1998) the press reviews of the ballet festival organised by the Arts Council of Ceylon in 1961 singled out Chitrasena’s production as the only one fit for praise and thought to fit the definition of a ballet, while the pieces presented by others were slated. His ability to conceive and present masterpieces that successfully melded different elements and entranced audiences presented unique theatre experiences for audiences. Despite premiering more than four decades ago, his three full-length ballets, Karadiya, Nala Damayanthi and Kinkini Kolama, retain their status as the most renowned mudra natya.

A classical ballet can be broken down into four major building blocks: plot, choreography, music and design. It is through the successful marriage of these four elements that ballets are elevated to a masterpiece and enter the realm of the classical. In its most complete form, a ballet can become a gesamtkunstwerk or a comprehensive artwork resulting from uniting multiple art forms. The process of creation usually involves collaborations between master-craftsmen/craftswomen from each of these four areas. In the process of creating these productions and their staging, Chitrasena was able to bring together leading artists from different fields, including Amaradeva, Somabandu, Ananda Samarakoon, Edwin Samaradiwakara, Lionel Algama, Somadasa Elvitagala and many more, in addition to several generations of dancers who were members of his dance company, ranging from the ritual dance practioners, the gurunnanses, to stage dancers.

Chitrasena’s impact on his collaborators is most clearly seen with Vajira: she would not only emerge as the principal female lead but took on the role of choreographer, in addition to devising a series of children’s ballets with the younger students at the Kalayathanaya.

However, there is a fifth element: the creator-director, who provides the vision, drives the collaboration and ensures a complete, final product. Each dance tradition has its own pioneering genius who is generally credited, not necessarily for producing the first ballet of each tradition, but for creating productions that are widely seen as epitomising it: Marius Petipa for the three-act classical ballet, Tagore for pre-independence Indian dance dramas, Rukmini Devi for Bharata natyam dance dramas and Chitrasena for mudra natya. Even his staunchest critics who contest Chitrasena’s contribution to bringing the Sri Lankan traditional dances from ritual to stage and setting the standard for dance theatre, concede his role in the development of mudra natya. For others such as Ravibandu, he is seen as playing a crucial role in both areas, including as “father of Sri Lankan ballet”:

“This epithet was given to him not because he was the first, but because he set the standards, creating Sri Lanka ballets in a more artistic and sophisticated manner. Many professionals, amateurs and school-level teachers all followed the form that he showed. That is why he is called the Father of Sri Lankan ballet.”

Investigating the process through which these ballets were crafted and staged, highlights the unique underlying collaborations, but also draws attention to the highly distinctive influence that Chitrasena had in conceptualising and executing these masterpieces.

(Mirak Raheem is a researcher currently working on a soon to be

published book about Chitrasena)