Playing a pivotal role in the ‘petition in the shoe’

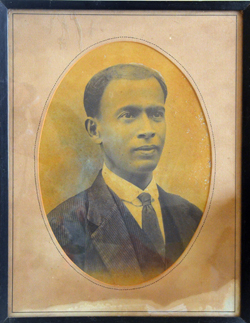

J.E. Gunasekera (extreme right and below): Call to serve the country came in 1915

“The petition in the shoe” is a legendary part of the struggle leading to our Independence from the British. Yet few know the full cloak-and-dagger story of this memorandum which disproves the idea that Ceylon got its Independence on a concessionary platter- as a minor repercussion of the British Raj collapsing.

Few recall the name of James Edward (JE) Gunasekara today. Yet he was as pivotal to the petition and its aftermath as E.W. Perera and F.R. Senanayake.

It was JE who, with the petition sewn into his shoe heel, travelled to Madras- to atpass it on to E.W. Perera on the next leg to London and to the British Colonial Secretary where it was to become a cause célèbre- exposing the brutalities of the colonial government of Ceylon following the 1915 riots shocking everyone from King George V to the poorest miner. Many British broadsheets denounced their actions and consequently a strict order was given to the British administrators to stop inhuman treatment of Ceylonese.

JE’s grandson Dhammika Gunasekara is one who still remembers the passed-down tales. He has many a family portrait, among them one of JE at a grand dinner in London in the 1920s.

JE, born in 1885 and having left S. Thomas’ College, then at Mutwal, was a teacher at Ananda College and later principal at Mahabodhi Vidyalaya, Maradana, founded by the Anagarika Dharmapala who was his guru-mentor.

JE, born in 1885 and having left S. Thomas’ College, then at Mutwal, was a teacher at Ananda College and later principal at Mahabodhi Vidyalaya, Maradana, founded by the Anagarika Dharmapala who was his guru-mentor.

His call to serve the country came in the calamitous year of 1915 when clashes between a Buddhist perahera and a mosque triggered the Sinhala-Muslim riots. Beginning in Kandy in the tail end of May, the riots spread across the country and by June 2, British Governor Robert Chalmers declared Martial Law.

Scarier than the riots were the measures taken against the rioters. The Army Commander H.H.L. Malcolm asked his men to shoot “through the heart any Sinhalese that may be found on the streets”. Many were killed and many prominent Sinhalese were arrested- among them F.R. Senanayake, D.S. Senanayake, D.B. Jayatilaka, W.A. de Silva, F.R. Dias Bandaranaike and E.T. de Silva. Most were members of the Lanka Mahajana Sabha, the prototype of the UNP, of which JE was also a member.

IGP Herbert Dowbiggin is painted for posterity in the vilest black due to the way he dealt with the rioters. He sentenced the Anagarika’s brother Edmund Hewavitarane to life in penal servitude at Jaffna Prison, where he died due to insanitary conditions and purposeful lack of medical care.

Dhammika Gunasekera: Still remembers passed-down tales

One of the most shocking executions was that of the 26-year-old Captain Henry Pedris. The bloodstained chair in which he was executed was shown to other riot leaders- an image that for many Ceylonese was the end of any delusions about the regime. The Havelock Town statue of young Pedris, today, stands near the Isipathanaraamaya, built in his name by his family.

It was against this backdrop, says Dhammika Gunasekara, that F.R. Senanayake dictated the petition, drafted by Dhammika’s grandfather. FR got a cobbler from Kurunegala to insert the petition into the heel of a shoe, and JE was sent over to Madras in the guise of a student from Talaimannar in a ship. The cobbler was kept within FR’s house till the letter- through E.W. Perera was due to reach the Secretary of the Colonies in London, Bonar Law later Prime Minister.

The reverberations of the petition so perilously delivered may today seem somewhat vague, after all harsh action was not taken against the Governor or the IGP but it remains the first clarion call for Independence which stirred the middle-class Ceylonese into prompt action.

Also instrumental to the release of the Sinhalese leaders, and the transfer of Chalmers and his Head of Military, was the mission to London of Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan. After his triumphal return the Sinhalese leaders took turns to draw the horse carriage in which Sir Ramanathan sat, all the way to his Ward Place house.

After coming back from Madras, JE, not being an overly prominent activist was not imprisoned, and continued to host at his house the clandestine meetings of the Lanka Mahajana Sabha.

In 1920 he married a girl from Musaeus College where he taught. Four years later he would be sent to Oxford on a scholarship by F.R. Senanayake, to return and continue as headmaster of Mahabodhi Vidyalaya.

London 1927: J.E. Gunasekera, amongst the members of the Association of Ceylon students in Great Britain and Ireland attending their annual dinner

In 1931, when his fifth child who was Dhammika’s father was hardly two years, JE passed away aged 46. His young widow was much harassed by the minions of the British government, who would search their house for any secret documents (even rifling through the pillows, says Dhammika) so she left for her ancestral home in Matale with the children.

It was years later, in 1966, that part of Kynsey Road near Maradana was named J.E. Gunasekara Mawatha, near two schools where he had served. With his siblings, Dhammika today is sifting through the family’s hoard of memories to unearth more of the patriot’s life and his work with the Anagarika and the Lanka Mahajana Sabha.