Congenital Hypothyroidism: A heel prick in time ensures a life that is fine

Aravinda was frowning when Anupama came out of the bathroom and asked anxiously, “What happened?”

“The call came from the hospital,” he said. “Our baby will need a second blood test.”

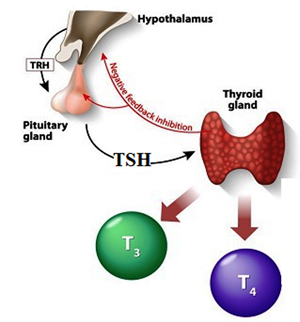

Figure 1

Two days earlier, they had come home from the hospital, with Tharaka, their newborn. Prior to discharge from the hospital, the baby had been given a heel prick for a blood sample collected on to a special paper (called a dried blood spot) and the results had just arrived. The test was for thyrotrophin or thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) assessment. If the TSH level is higher than expected, doctors have a suspicion regarding a condition called Congenital Hypothyroidism (CH).

Congenital Hypothyroidism (CH)

“Congenital means present at birth; hypothyroidism is a condition in which the person does not make enough thyroid hormone,” says Professor Manjula Hettiarachchi from the Nuclear Medicine Unit (NMU) at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Ruhuna.

A normal thyroid gland receives TSH from the pituitary gland, and in turn produces the thyroxine hormone T4 and the triiodothyronine hormone T3, as shown in Figure 1. In a few cases (typically 1 in 1500 or so) this thyroid hormone production process is impaired. The reasons could be an absent or misplaced thyroid gland, a hereditary cause – maternal iodine deficiency or maternal thyroid condition. This causes a build-up of TSH, which is the indicator used to test for CH. If left untreated, CH may slow down a baby’s physical development and cause intellectual disability leading to mental retardation due to irreversible neural damage in the brain.

The good news however, is that if a health screening is carried out in the early days of a baby’s life, it can be treated fully with thyroxine replacement therapy, avoiding serious health conditions in the future, or significantly mitigating such conditions.

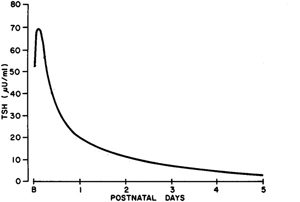

Figure 2

A baby’s TSH levels are invariably high in the first 24 hours (Figure 2). This makes it difficult to know whether high TSH levels are due to a (normal) thyroid surge or to an abnormally functioning thyroid gland. If the TSH level is checked on days 3 to 5, normal TSH level variation is less, and setting a critical cut-off value for it is easier. In Sri Lanka however, while almost all deliveries are performed in hospitals, a large number of newborns are discharged within 24 hours; hence over 70% of TSH samples are collected within 12-24 hours of life.

A research study at the University of Ruhuna involved a survey to establish some of the above parameters for a Sri Lankan population. A significant part of the early research was to establish the cut-off level of TSH that would account for the time variation of TSH shown in Figure 2. If the cut-off is set too high, a case of CH may be missed (i.e. a false negative result). If it is set too low, there will be many false positives, causing parental anxiety and additional testing burdens on the health system. Today however, the technology employed in the testing is able to compensate for the timing effect.

All babies get a heel prick

The Newborn Screening Programme for Congenital Hypothyroidism of the Nuclear Medicine Unit (NMU), Faculty of Medicine, University of Ruhuna, started on September 21, 2010 in the presence of Sri Lanka’s Minister of Health. This was the culmination of a series of studies carried out by the NMU since 2006 with the assistance from the Perinatal Society of Sri Lanka, Family Health Bureau & Medical Supplies Division of the Ministry of Health, and a research grant from the National Research Council (NRC). The newborn screening programme has been taken up by the Ministry of Health and now covers virtually all newborns. This kind of coverage is possible because of Sri Lanka’s universal health coverage, and also because virtually all births take place in hospitals where testing is possible, rather than in homes (as in some parts of the world).

The laboratory in the Faculty of Medicine at Galle performs what is called a “time-resolved fluroimmunoassay”, which involves the measurement of photons (or light) when the extracted blood from the paper is treated with reagents. This is why a Nuclear Medicine Unit is required for such screening. If the heel prick test reveals high thyrotrophin levels (i.e. screening positive), a second test, for serum thyrotrophin levels will be performed immediately, using a sample obtained from a vein. The parents are kept informed via telephone (or SMS) contact, or through the primary health care team comprising the Medical Officer in Maternal and Child Health (MO/MCH) in each district, Medical Officer of Health (MOH) and the Public Health Midwives (PHM) who handled post-natal care at the field/family level.

Figure 3

The National Research Council of Sri Lanka supported this programme not only with initial funding for equipment in 2008, but also in 2011 to develop a health education programme based on the Health Belief Model (HBM) on mothers’ participation. The proposed educational programme was very effective in changing certain aspects of mothers’ behaviour and several leaflets in Sinhala and Tamil language were prepared for distribution. Further, an online platform (http://www.nsisd.ruh.ac.lk) was created for dissemination of results and more information on newborn screening for CH in Sri Lanka (Figure 3).

The treatment for CH is simple but it should be started within four weeks of a baby’s birth. Until then, the baby is protected by its mother’s thyroxine through breastfeeding. Replenishment of the baby’s thyroid hormone will start soon after a baby is diagnosed. The thyroxine tablets (which can be crushed and administered with a sip of water or dissolved in water) contain L-thyroxine, a synthetic form of thyroid hormone, but with a chemical structure identical to that produced by the normal thyroid gland.

The costs and benefits

The National Research Council, together with Professor Hettiarachchi, has recently tried to calculate the benefit/cost ratio for the screening programme. This is a rare instance of research benefits being actually quantified. The heel prick test would cost a few hundred rupees per baby; while the costs for follow up and medication for those testing positive (but averaged over all babies tested), would double this. The benefits would be savings in health care for individuals who would otherwise have developed physical and mental impairment as a result of CH not being detected. The calculation is based on total costs to the programme in a given year with the projection of upcoming costs in the follow up for an assumed lifespan of 75 years. The details are included in a forthcoming scientific publication, but the benefits are such that every rupee the government is spending will yield a nearly four rupee benefit to society.

Given that there are around 300,000 births per year in Sri Lanka, the country would be saving a few hundred million rupees per year as a result of these heel pricks. The actual research costs themselves, essential for conducting the surveys and procuring equipment, would pale into insignificance in the light of these health sector savings.

This work, which has spanned many years, was commenced at the University of Ruhuna by Professor Manjula Hettiarachchi (manjulah@med.ruh.ac.lk; 0706325425), Emeritus Professor Chandrani Liyanage and Professor Sujeewa Amarasena, from whom more information can be obtained. The research was funded by the National Research Council under grants IDG 08-08 and IDG 11-160.

Asitha Jayawardena was commissioned to write this article as part of the science publicity programme of the National Academy of

Sciences of Sri Lanka.