News

Alarm over return of leprosy: Rising cases among children

An increase in the number of young children reporting with leprosy in the country in the past 10 years has prompted the World Health Organisation (WHO) to declare Sri Lanka as a highly endemic country in the region.

The WHO has determined that the high proportion of children among new cases reported in Sri Lanka in 2019 proved the disease, which is curable, be actively being transmitted.

According to the Anti-Leprosy Campaign (ALC) statistics, 181 children under 15 years have reported positive in 2019 amounting to 10.9 % of the total cases reported for the year. The number of afflictions among children has been fluctuating in the past 20 years (2000 and 2019) within a margin of ten percent.

The figures indicate that the Western Province has the most number of child patients with 81 reporting with symptoms. This is followed by the Eastern Province with 36 cases, the Southern Province with 17 cases, the North Central Province with seven cases and the Uva province with six cases.

Among the new cases in the Western Province last year, the Gampaha district reported the most number of afflictions among children with 36 cases, including 12 deformities. The Colombo reported 26 cases with 14 deformities.

In total, 93 cases of leprosy related deformities were reported around the country. The ALC attributes the trend to lack of awareness, delays in diagnosis due to inaccessibility to health services and economic constraints.

ALC Director Champa Aluthweera said health workers in some areas did not have the skills and training to identify the cases at their early stage and this also had contributed to the increase in cases.

The total number of patients afflicted with leprosy last year was 1,749 including 43 relapse cases and 44 defaulters.

Statistics also show about 455 patients presented themselves late for treatment, six months after the appearance of the first symptom.

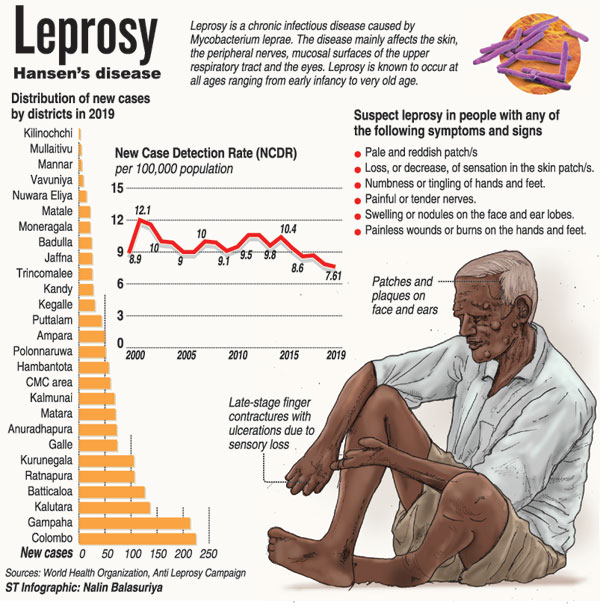

The ALC said New Case Detection Rate (NCDR) in 2019 had been 7 to 12 cases per 100,000 patients or some 2000 new cases every year for the last 20 years.

Cases with deformity ranged between 6 and 8 until 2015, then increased to 10 in 2016 but are gradually decreasing in the last three years.

Last year, the highest number of 224 new cases was reported from the Colombo district, followed by 213 cases in the Gampaha district, 136 in the Kalutara district and 16 in the Ratnapura district.

The Batticoloa district’s 126 new cases and the Ampara district’s 50 new cases last year were the highest for the two districts in the past 20 years.

These shocking figures have underscored the need to strengthen the process to detect unreported cases in the two districts, Dr. Aluthweera said.

The ALC has intensified its screening facilities in untouched pockets. Last year 5,004 contacts of patients were identified and screened. Of this, 108 turned out to be positive.

The increased prevalence of the disease among young children and females has made the health authorities focus on pockets among factory workers and in schools.

Special medical inspections are being carried out in schools by public health inspectors.

In Katunayake and Biyagama, the ALC, through its mobile service, is conducting tests, going house-to-house checking for early diagnosis among the BOI and free trade zone women.

Also it has introduced 19 satellite clinics around the country. Last year, 15,559 people among slum dwellers and crowded populations were screened, leading to the detection of 47 new cases, including two cases with serious deformities.

In various untouched pockets, ALC’s awareness programmes have brought in positive results, with patients voluntarily seeking treatment.

Private doctors also has been contributing in a great way referring patients to dermatological units in state hospitals.

Sri Lanka eliminated leprosy as a public health problem in 1995 when it reported less than one patient in 10,000 people. But in 2013 leprosy was declared as a notifiable disease.

Between 2016 and 2020, Sri Lanka joined the global drive towards a leprosy-free world by initiating action, ensuring accountability and promoting inclusiveness in its leprosy eradication task.

But 25 years after eliminating the disease, the country is once again faced with the task of containing it. It is argued that the low priority given for leprosy control after 1995 has contributed to the present hike.

Health experts said it is important to keep leprosy in the agenda of regional district health services and epidemiology units for effective eradication.

Now they have set a 2030 target to eradicate leprosy completely.

The health sector is also lobbying lawmakers to repeal the Lepers Ordinance 4 of 1901 introduced by the British under which patients with leprosy were segregated and treated.

With the introduction of the mutli-drug therapy, leprosy patients are now treated in their home settings.

This has rendered admission to leprosy hospitals in Hendala, 6 km from Colombo, and at Manthivu in Batticoloa redundant.

Early detection of symptoms and seeking treatment immediately rescue patients from damage to peripheral nerves that can result in deformities, experts say.