Chugging down memory track to ‘Summit Tunnel’, Pattipola

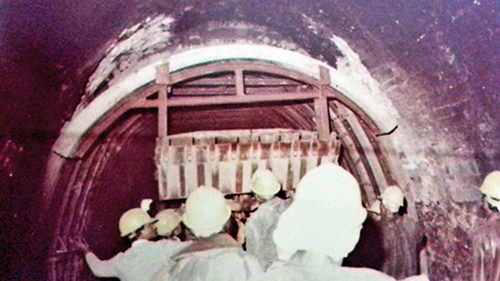

Crown concrete panel launched into position

Tunnel No 18 or the ‘Summit Tunnel’ is 220km from Colombo on the upcountry railway line, around one kilometre from the highest point of the railway summit (1898.1m above mean sea level). It separates the Nuwara Eliya District from the Badulla District and is also a boundary demarcation of the Central and Uva provinces.

The tunnel was exposed to varying climatic conditions. At times, there is rain on the Colombo end of the tunnel mouth and bright sunshine on the Badulla end. This may have contributed to the tunnel’s rock strata weathering and fissuring.

The tunnel first collapsed in 1951, when a small charge was instituted to remove a boulder which was about to hinder the passage of trains. Earth with mud came down in such huge quantities through a cavity in the crown area that the Colombo end was flooded.

The Railway called on one its most senior engineers from the Colombo head office, Edwin Black, assisted by District Engineer N.A. Vaitialingam and his assistant J.Paul Senaratne. They initially erected two sleeper cribs on each side of the debris and spanned the collapsed area from beneath with steel beams, driving them from one side to the other. Then they slid on beams, steel arches made of rails, and hoisted them into position to form a steel shell across the collapsed area.

The crevices between the tunnel wall and the arches were packed with sleeper planks. Once it was in position, they were able to clear the earth.

Services resumed, but there were shortcomings. The arches were intruding on to the standard required clearance for safe passage of trains. Thus, trains were required to stop before entering the tunnel, mainly to inform passengers to keep their heads and hands inside as they may knock on the arches.

There were fatal accidents, particularly during the Sri Pada pilgrimage. Despite the warning, some hit their heads on the arches. With time, the rail arches were fast corroding owing to moisture and sleeper planks were perishing. By 1967, the tunnel was again the centre of discussion.

Around the mid-60s, local and foreign consultants were consulted about permanent repairs. One suggestion was to cut open the tunnel up to the affected area but this would have been costly with earth disposal an exercise by itself. An ADB team suggested making an open cut excavation up to the cavity, and drilling into it as well as concreting the cavity from the top.

J. Paul Senaratne, then Chief Engineer Railway Way &Works, suggested that reinforced concrete cylinders be sunk up to a certain distance above the cavity; steel shutters with windows be driven from there up to the cavity; the cavity be filled up with rubble through the windows; and, the affected area re-lined without disrupting the train service.

But this was time-consuming and, again, required significant earth disposal. Further, if the steel shutters did not move due to boulders interrupting their passage, such rock would require blasting. There were fears such action would give rise to a similar situation as in 1951. The idea was dropped.

I passed out as a civil engineer in 1973 from the University of Moratuwa, joined the Mahaweli Development Board (MDB), and was assigned to the Bowatenna Project. I worked in the Bowatenna Irrigation tunnel and gained sufficient experience in tunnel excavation as well as remedial measures to collapsed sections in this tunnel.

In 1975, as a new employee at the Railways, I was assigned with planning and providing a design for resurrection of the Pattipola tunnel due to my prior experience in the Bowatenna project. The railway had certain data on soil borings from the Geological Survey Department which revealed that the cavity extended 25ft above the crown and had an overburden of 100ft at this point.

Soil samples revealed that the rock was fractured quarzitic gneiss with weathered feldspar. Having studied the soil conditions, I immediately consulted Specialist Engineer Geology of MDB, P.M. Siththamparapillai who recommended that loose earth be consolidated by pressure grouting before any attempt was made to remove the corroded rail arches.

Hence, on two occasions, 1976 and 1979, the Irrigation Department did pressure grouting under my direction. But removing rail arches remained tricky because sleeper planks of nine feet in length were supported by many rail arches. To carry out an in situ lining, a large area had to be exposed without any support.

Prof. Dayantha S. Wijeyesekera of Moratuwa University and my father, L.S. de Silva (Retired General Manager Technical, Railway), then working at Moratuwa University advised me to adopt precast concrete panels in arches for permanent repairs. I considered the weight of each panel and flexibility of handling these inside the tunnel and then designed two-foot, reinforced concrete panels, dividing each arch to five segments (i.e., two bases, two haunches and a single arch type panel for the crown).

In February 1981, under my guidance, a team went to Pattipola for permanent repairs. Implementation we knew, would be challenging and I was also mindful of staff health and safety. I requested the railway to provide me with one of the five motor vehicles the Way & Works sub-department had. This was declined. I started work using a trainload of materials and equipment.

On the very first day, the Chief Engineer visited the site. While workmen were pulling the sleeper planks, one rolled over and hit one of them. He was rushed to the Nuwara Eliya hospital in the Chief Engineer’s vehicle, prompting him to allocate the vehicle I had wanted. The workmen thought this injury a bad omen and insisted that we invoke the blessings of God Saman before starting again.

Oxygen and acetylene cylinders required to cut the rail arches came by train from Colombo to Nanu Oya, were collected from the station by a motor trolley. Worker rations were sent from Nanu Oya because Pattipola, a small town with no electricity was covered in thick mist by 5 p.m., and had just one small tea boutique with a few daily needs.

The repairs were carried out in a sequence. Rail arches on either side of the actual collapsed area were removed. Seven steel plates were driven to cover the actual collapsed area (cavity) which was estimated to be 14ft by 8ft. Steel plates were rock bolted at the ends.

The 29 rail arches that were directly under the cavity were gradually removed, while supporting the steel plates with temporary rail arches made out of light rails. Concrete footing was built on either side for a length of 40ft. Base-and-haunch concrete panels were placed using a device innovated at site. Light rail was fixed to the underside of panels. The base-and-haunches were launched to position, propped by Acrow prop.

The crown concrete panel was placed by means of a front-end loader, with bucket modified. The idea of utilizing the front-end loader was from a student from Dharmaraja College Kandy whose father, D.N. Munesinghe, was the Inspector of Tunnels.

The underside light rail of all panels was welded to each other and the crevices between panels and tunnel wall concreted.

Eighteen concrete arches were fixed in this manner to cover the area that had steel rail arches earlier. Train service then resumed at restricted speed. After curing the concrete for 14 days (as there was no rapid hardening compound), the props and the underside light rails of panels were removed. Service resumed at normal speed.

I wish to emphasize how work can be done with limited resources when engineers are creative and innovative. With such vision, they can limit foreign involvement and, thus, expenditure. This repair was done with meticulous planning despite limited technical resources, machinery and equipment–with staff who worked determinedly in adverse climatic conditions for six weeks from February to March 1981.

(Eng. Priyal de Silva is Retired General Manager Sri Lanka Railways, Past President, Institution of Engineers Sri Lanka and

Past Chairman, Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport Sri Lanka)