Art, architecture: ‘Useless if you don’t know how to laugh’

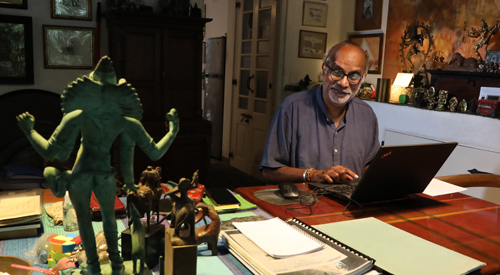

Art everywhere you look: Anjalendran at work surrounded by paintings and objets d’art and (below) his preferred mode of transport

Open the faded periwinkle blue and lemon yellow doors to No 60/8, Shanthi Lane, Battaramulla, and you enter a realm where art is omnipresent. Art claims every minute space on the walls including the bathrooms and storerooms and the whole place is just crawling with objets d’art – from Laki Senanayake’s owls to Italian antiques, Natarajs and baskets of batik Easter eggs- all blending harmoniously.

Here, in sarong, reigns C. Anjalendran- the maverick architect who owns a three-wheeler, is probably one of the few people alive to have known Geoffrey Bawa intimately and himself a master whose work Bawa drank in with sheer enjoyment probably because ‘Anjel’ (as the near and dear call him) dared to use colour and clutter, and much more ethnic detail than the circumspect Bawa did. When Ena de Silva wanted to know what colours she should use for the Triton Hotel batiks, Bawa’s answer was “any colour as long as it’s black, white or gray”.

Turning 70 this year, Anjalendran comes from an old Jaffna family. His grandfather C. Suntharalingam was Minister of Trade in the first Ceylonese government. Having schooled at Royal, Anjalendran was the first student from the first batch to graduate from Katubedde University’s brand new Department of Architecture.

Turning 70 this year, Anjalendran comes from an old Jaffna family. His grandfather C. Suntharalingam was Minister of Trade in the first Ceylonese government. Having schooled at Royal, Anjalendran was the first student from the first batch to graduate from Katubedde University’s brand new Department of Architecture.

After a research Master’s at the University of London, Anjalendran came home to practise. For ten years, he worked for Bawa as an apprentice – unpaid- 40 to 50 hours a week. It was at Bawa’s side and mixing with that coterie which included Ena de Silva, Barbara Sansoni and Laki Senanayake that Anjalendran really imbibed the craft.

“I lived in a time of giants,” says Anjalendran. That he blossomed in their shade he readily admits. While teaching was not one of Bawa’s gifts, weekends at Lunuganga and being in Colombo where Bawa tackled head-on the daily problems on site and at the desk at Alfred House Road, imparted almost all that was crucial.

Early on, Barbara Sansoni with her inveterate love for old buildings got Anjalendran to help with the book Architecture of an Island, which he worked on for nearly ten years. He also worked with Ena on all her buildings save the batik shed at Aluvihare and it was from him that she acquired the Hindu accents- including the Ganeshas or Aiyanaike she would often weave into her batiks.

Anjalendran is doubtful about the modern ‘cult’ celebrating and perpetuating Bawa:“a lot of vulgarity and over-decoration” where the pretence is to ‘follow the footsteps’ of the master. “One word Bawa always used was ‘restraint’,” he says, pointing out that Lunuganga though artificial looks completely natural as if demi-god Pan himself had planned it.

Having helped the estate at Bentota take its voluptuous shape over all those weekends as apprentice, Anjalendran naturally loves Lunuganga.

“In fact I have this new theory. Now you know it was Lunuganga that made Bawa get into architecture. When he was doing his English Tripos at Cambridge his colleagues took him to see English gardens and houses. I think he really does gardening using building material because it’s only in gardens you get vistas and promenades… the best example for this would be the University of Ruhuna.”

Anjalendran himself, in contrast to Bawa, has ‘never signed a design contract’ in his life and hardly ever did any commercial buildings. Remarkable in his portfolio are the SOS children’s home in Galle- considered the most beautiful in Asia which was coloured by Barbara Sansoni and the Mount Cinnamon Villa in Mirissa with giant sculptures depicting a strange bestiary and dramatic views of the ocean. Currently, he is designing a new Guru-gedara for the Chitrasena Kalayathanaya and an open ward cancer hospital in Ragama.

An inside view: Anjalendran’s Battaramulla house. Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Anjalendran’s buildings tend to be logical when compared with Bawa’s. Like his own house, everything is functional while it’s the end result with all those serried armies of paintings, antiques and bibelots that is aesthetic. Whereas Bawa, as in Kandalama, focused on an aesthetic experience and would add functions to it “as he went along.”

Anjalendran has always maintained he has no style. There just happens to be a bunch of ‘constants’ in his buildings. “All of my rooms have cross-ventilation; most of my works have a promenade; and in most the structure is not decorated,” though he admits that compared to Bawa, an eclectic, he may betray some style.

It was Bawa again who passed on the travel bug to Anjalendran. Owing his own eclectic genius more to inveterate and insatiable travelling than to classroom education, Bawa encouraged him to be vagrant and ‘collect’ buildings across the world.

“Geoffrey always said if you have money you should travel and you should travel in Rajasthan and Tuscany, and that, given the choice, he would choose Rajasthan.”

Now Anjalendran can say he has travelled extensively thanks to his best friend Dharmavasan who has lived in Holland and Rome, David Robson who was a former tutor and his client Miles Young who sponsors sorties to faraway and often little-known places.

Teaching history of architecture, an auxiliary pleasure has been that in class he would discover places “I haven’t seen and what I ought to go and see.” Amongst the buildings he loves are the temples and palaces of Rajasthan, and the Amir Palace of Jaipur with its many levels and gardens and the Castelvecchio museum in Verona by Carlo Scarpa rather like a medieval monastery (the austere lines of which take you to the Lunuganga houses).

But it was at home he found Arcadia. The Kaludiya Pokuna monastery secluded from the pilgrim throng of Mihintale with boulders and dry zone flora reflected by the serene pond was a magical revelation. “The boulder gardens,” he reminds, “are uniquely Sri Lankan; you don’t get them in other parts of the world except at Hampi (of the Vijayanagar empire).”

Low cost: The house he built for Kumar

Equally impressive was Sesseruwa Rajamaha Vihara with its giant rock Buddha statue and small Kandyan outhouses.

The porous line between archaeology and architecture submerges when Anjalendran says he wrote the most authoritative work on Sinhalese gardens. “It’s a realm where man has left over and nature has taken over, just like at Kaludiya Pokuna. You never know where one ends and the other starts.”

But probably the biggest love of his life is art, his houses brimming with paintings – George Keyts to Sybil Wettasinghes.

“I always believed, when I started earning, that I will give half of my money to artists,” he says. “In this house there’s a lot of art that no one bought.”

Anjalendran’s first Richard Gabriel was bought for 300 rupees from the Sapumal Foundation.

“Harry Pieris, who ran Sapumal, would tell me, ‘Mr. Anjalendran, you buy this- it’s 450 rupees. You pay me over six months’. And that was ok- because Geoffrey only paid 300 rupees!” Anjalendran guffaws.

“The truth is, once one became hooked on art, one went around and those days it wasn’t all that expensive. You could buy a huge Laki for only 2000 rupees.”

“But one thing is I spent a lot of time with artists. I encourage my clients to buy art. I think artists have a right to live which most people don’t think they have. I enjoy art.”

Anjalendran regrets that in Sri Lanka, architecture is “based on the rich house and the hotel”, and has nothing to do with the rest.

The house he built for his factotum Kumar and his wife Savithri, completed just before the pandemic, is thus an act of open rebellion. It is a low-cost two-storeyed house but with art, antiques, old cupboards and salvaged kovil peacocks in wood- all jazzed up with colourful modern furniture.

The supreme irony remains that while Bawa and his accomplices brewed a revolution, all they meant to do was ‘just enjoy themselves’. No lofty ideals eddied their horizon. Anjalendran’s favourite quotation is -‘I don’t want to change the world, I want to make a few people around me happy.’

Though in retrospect it has all been celebratory, they didn’t revel in the glory. Donald Friend, who in many ways was an inspiration to the set, once said “like all young men, I set out to be a genius. Laughter, mercifully, intervened.”

Anjalendran backs the line with the emphasis of finality. “At the end of the day, architecture and all are fine, but if you don’t know how to laugh – useless!”