News

Finance Ministry admits Rs. 15.9 billion “foregone revenue” on sugar imports

The Finance Ministry has admitted that the Government’s decision to drastically cut the tax on sugar in October last year had caused a “foregone revenue” of Rs 15.951bn while not achieving the desired effect of reducing retail prices.

Treasury Secretary S.R. Attygalle insisted that his office did not term this as a “loss”. Rather, it was foregone earnings — the difference between earnings actually achieved and earnings that could have been achieved by way of tax — arising from a policy decision taken by the Government.

This is also emphasised in the Finance Ministry’s report to the Parliamentary Committee on Public Finance. It states that a revenue loss is incurred when a tax is charged and collected on a reduced tax base by under-invoicing or under-valuation; on a wrong tax rate or misclassification of goods; or when the tax on taxable goods is not charged or collected. None of these was relevant to the present case.

This is also emphasised in the Finance Ministry’s report to the Parliamentary Committee on Public Finance. It states that a revenue loss is incurred when a tax is charged and collected on a reduced tax base by under-invoicing or under-valuation; on a wrong tax rate or misclassification of goods; or when the tax on taxable goods is not charged or collected. None of these was relevant to the present case.

But Opposition parties say the Ministry is just splitting hairs and that there is not only a massive loss but a “scam” to favour political henchmen. Additionally, a massive inflow of sugar imports prompted by the next-to-nothing tax has also led to large foreign exchange outflows.

They reiterate that a company named Pyramid Wilmar (Ltd) struck rich from the tax revision and rapidly became market leader, wielding huge sway.

The Finance Ministry has said it only was carrying out instructions from the President’s office as conveyed by Presidential Secretary P B Jayasundera. But industry players ask why the decision had not been backed by solid analysis.

They cited multiple sources as saying the President had been “misled” by a former senior Lanka Sathosa official who had maintained that cutting the sugar tax would have the ripple effect of reducing the price of multiple other items—including the poor man’s cup of plain tea. This did not happen. What did occur was a profusion of sugar imports, chiefly from India.

“This is worse than the floodgates being opened,” a sugar importer said this week. “No, the floodgates were completely demolished and a river of sugar turned towards Sri Lanka. And it keeps coming, and coming and coming.”

In general, between 550,000 and 650,000MT of sugar is brought in annually. In 2019, the monthly average imported was 46,346MT. After the tax revision, however, a total of 320,627MT was imported between October 14 and February 20 alone—a monthly average of 80,156MT.

On October 13 last year, the Government cut the special commodity levy (SCL) on sugar overnight from Rs 50 per kilo to 25 cents per kilo. On November 10, it hastily imposed a maximum retail price (MRP) of Rs 90 for a kilo of packed white sugar, Rs 85 for a kilo of bulk white sugar and Rs 80 for a kilo of sugar on the wholesale market. The objective, ostensibly, was to make sugar cheaper for the public.

On October 13 last year, the Government cut the special commodity levy (SCL) on sugar overnight from Rs 50 per kilo to 25 cents per kilo. On November 10, it hastily imposed a maximum retail price (MRP) of Rs 90 for a kilo of packed white sugar, Rs 85 for a kilo of bulk white sugar and Rs 80 for a kilo of sugar on the wholesale market. The objective, ostensibly, was to make sugar cheaper for the public.

This did not work as anticipated, the Finance Ministry has now admitted. The Government’s attempt to limit sugar inflows by introducing a system of import control licences–and then withholding permits from October 29 to November 20–also flopped. So did the MRP strategy.

Between October 14 last year and February 20 this year, sugar was sold at between Rs 125.04 and Rs 118.13 (monthly average price). The lowest it went to was between December 1 and 15, when the average was Rs 111.64. The State-owned Lanka Sathosa Ltd did sell sugar at the MRP (maximum retail price) but made losses by buying sugar at higher prices from the wholesale market.

The Finance Ministry report observed that the average retail market price of sugar did not drop below Rs 100 a kilogramme during the period under review. It also stated that it was possible six major sugar importers in Sri Lanka’s oligopoly market structure “earned a kind of additional profits”.

But sugar importers say only two categories did well: Those who had no stocks of sugar when the tax revision occurred and could therefore buy fresh consignments at the new duty; and Pyramid Wilmar, which had 8,237 metric tonnes (MT) in a bonded warehouse and this stock could now be cleared at 25 cents per kilo. (In the case of bonded warehouses, the tax is paid on goods at the time of leaving the facility and not at the port, as it is for other importers).

Other sugar importers had 90,000MT in stock for which they had already paid Rs 50 per kilo as levy. “We made hefty losses on those,” the importer said. A strong industry lobby forced the Government to promise it would raise the special commodity levy (SCL) to Rs 40 per kilo in February. This was not done. Instead, the 25-cent levy was extended.

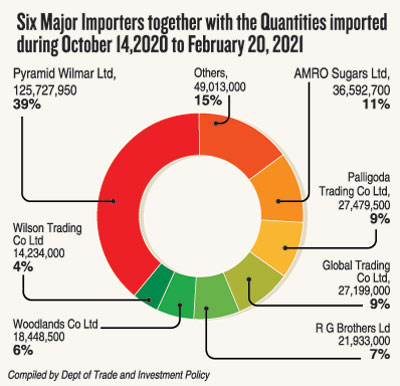

Pyramid Wilmar, being a global force in the sugar trade, flooded the market with its own imports at short notice. The Finance Ministry’s data shows that Pyramid Wilmar imported nearly 40 percent of the 320,627MT of sugar that came into the country between October 14 and February 20. The rest was shared among six importers and “others”.

On November 3, just days after the SCL was slashed, the largest sugar ship to arrive in Sri Lanka in 30 years docked in Colombo — a vessel with 26,000MT in 1,000 containers for Pyramid Wilmar Ltd. It had been destined for another market but was diverted to Colombo mid-sea for Pyramid Wilmar ti gain immediate advantage of the tariff change.

The slashing of the SCL on sugar contravened the Government’s own policy of May 2020, when it raised the same tax from Rs 33 to Rs 50 to discourage imports and save foreign exchange, promote local production and to control the spread of diabetes, obesity and other ailments.

Sajad Mowzoon, director of Pyramid Wilmar, did not respond to text messages seeking a comment.