News

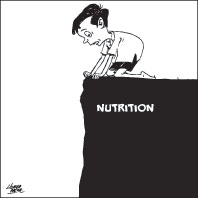

Rising obesity rates catch children, women

Child obesity has risen since COVID shutdowns began, adding to a nutritional triple burden of under-nutrition, high levels of obesity and vitamin and mineral deficiencies, studies show.

While malnutrition is decreasing, obesity is taking its place in the nutrition crisis, the President of the Sri Lanka Medical Nutrition Association, Dr. Renuka Jayatissa, said.

The level of obesity among children under the age of five has increased when compared with pre-COVID data.

Dr. Jayatissa attributes this to the confinement of children to homes, saying, “Children are not as active as usual and tend to eat more junk food when they’re at home”. She noted that childhood obesity leads to diseases in adulthood.

Women are also becoming more obese, which carries especial problems when they are pregnant. According to statistics obtained by the health ministry’s Nutrition Division, 45 per cent of women of reproductive age are obese.

“The continued consumption of unhealthy food, which might be the only option available to certain parts of the population, is causing increased obesity in women,” Dr. Jayatissa said.

Conversely, a 2017 study carried out by the Ministry of Health in collaboration with the World Food Programme and the United Nations Children’s Fund showed a third of pregnant women were anaemic while 22 per cent were iron-deficient.

“Extremely sugary biscuits and drinks, which people tend to consume more of when they’re at home, is a concern,” Dr. Jayatissa said, adding that there were not many options of no-sugar food in Sri Lanka.

“Usually people should only take six teaspoons of sugar, but under these conditions, people are taking twice and thrice the amount.”

More than a million primary school children depend on the government’s school meal program for one of their meals every school day, the health ministry said.

“Some children come to school for the meal,” admitted Dr. Lakmini Magodaratne, the Director of the ministry’s Nutrition Division.

The government allocates Rs. 28 for each meal, and a meal makes up one-third pf daily nutritional requirements.

Dr. Magodaratne noted that the COVID-induced school closure period cut children off from this resource but said dry rations were distributed during this time to ensure that children still had access to nutrition.

Some 60-65 per cent of primary schools are in the meal programme, selected on the basis of nutrition vulnerability. While only primary schools are currently involved, in schools with fewer than 100 students, the programme feeds the whole school.

The health ministry has also initiated weekly iron supplement programmes for all primary school children through their schools.

Dr. Magodaratne said the availability and affordability of nutritious food was a significant challenge. “Behavioral changes in the society are a must,” she said.

She said anaemia, one of the conditions caused by deficiencies in vitamins and minerals, is decreasing across the nation but the rate was uneven depending on location.

In children under the age of five years, anaemia has decreased from 52 per cent in 1970 to 15 per cent in 2012. District disparities were noticed as Vanni accounted for 27 per cent of the population of anaemic children while Kegalle only had 5 per cent.

Anaemia is present across all socio-economic groups: 13 per cent of those found to be anaemic was found in the wealthiest quintile of people while 18 per cent was found in the poorest quintile, the health ministry’s statistics show.

Calcium deficiency is another problem, with the ministry’s 2017 study showing nearly half of children aged from six months to five years suffered in this way. Levels were highest in previously war-torn areas that experienced a lack of food security.

Dr. Jayatissa warned the COVID shutdowns could see a rise in diseases caused by vitamin D deficiencies – already a concern – due to reduced access to the morning sun.

A cross-section study by Dr. Jayatissa in Gampaha revealed rates of anaemia, iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anaemia in children aged 5-10 years in that district was 22.7 per cent, 22.1 per cent and 13.5 per cent respectively.

Iron deficiency in urban children was significantly higher than that among rural children, said the study, published in 2020 by Micronutrient Initiatives India.

Anaemia was significantly associated with children consuming tubers daily and eating fish only once a week.

Anaemia was significantly associated with children consuming tubers daily and eating fish only once a week.

Households with piped water had a higher prevalence of iron deficiency.

There was a correlation, although limited, between iron deficiency and children who were stunted

and wasted.

Wasting – severe weight loss that occurs due to a lack of adequate quality and quantity of food – affects 15 per cent of the population, one of the highest rates in the world according to 2016 figures from the health ministry.