Sunday Times 2

When Sri Lankan envoys walk slippery tightropes

UNITED NATIONS, (IPS) — Sri Lanka’s diplomatic debacle at the UN Human Rights Council meeting in Geneva— best reflected in a blow-by-blow account in the Sunday Times political columns – harks back to a bygone era when a senior career diplomat was offered a new posting as our Ambassador to the United States. But he gracefully declined the offer.

In a private conversation, “strictly off-the-record and not-for-attribution”, he told me: “Being a Sri Lankan ambassador in Washington DC -–or for that matter in Geneva— is like walking a slippery tightrope with the bucket of s—t on your head.”

In a private conversation, “strictly off-the-record and not-for-attribution”, he told me: “Being a Sri Lankan ambassador in Washington DC -–or for that matter in Geneva— is like walking a slippery tightrope with the bucket of s—t on your head.”

Perhaps, he was right because the Government at that time was virtually “blacklisted” by the US, as it battled charges of human rights violations and civilian killings in northern Sri Lanka. The task ahead for any envoy was not only to deny these killings but also justify the atrocities — if any.

As Americans would say: that’s diplomacy 101, defined as a complex and often challenging practice of fostering relationships in order to resolve issues — and advance a country’s national interest even under the most trying circumstances.

Meanwhile, over the years, governments of all political hues, sustained a longstanding tradition of appointing retired and ageing former military chiefs — including Generals, Air Marshals and Brigadiers– as ambassadors and high commissioners overseas.

A former career diplomat once posed what seemed like a logical reverse equation: “if former army chiefs can be appointed ambassadors”, he asked, “Why shouldn’t former ambassadors be appointed army chiefs?”

At a farewell dinner for Major General Shavendra Silva, Deputy Permanent Representative to the UN with Ambassadorial rank (2010-2015), and currently General and Commander of the Armed Forces, I predicted that Shavendra will be the first Sri Lankan ambassador in history who will be appointed Army Chief. And I was right, proving the argument that former envoys could well be appointed army chiefs.?

Like most foreign services worldwide, Sri Lanka has two categories of diplomats: career diplomats and political appointees. When career diplomats reach the age of 55 (optional) and 60 (mandatory), they go into retirement. But there are no such age limits on political appointees, mostly in their late 60s, 70s or even 80s.

Perhaps by accident or by design, some of our ageing political envoys were accredited to Egypt and died while in office — prompting an Egyptian Foreign Ministry official to tell a visiting Sri Lankan diplomat: “The only thing older than your ambassadors are our pyramids”.

Which reminds me: When Mrs Sirimavo Bandaranaike, the world’s first woman Prime Minister (who served three terms: 1960-1965, 1970-1977 and 1994-2000), addressed a summit meeting of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in Belgrade in 1961, she reportedly made a newsworthy speech with a riveting opening para: “As a mother and a Prime Minister.” And years later she was due to address another NAM meeting, this time in the Egyptian capital of Cairo in 1964.

As the delegates holed up in a hotel, overlooking the pyramids, were racking their brains for another catchy opening line, Felix Dias Bandaranaike, then a cabinet minister and a member of the Sri Lanka delegation, jokingly suggested the lead para for the speech: “As a mummy and as a Prime Minister”.

Mrs Bandaranaike apparently wasn’t amused — and what saved Felix from losing his Cabinet portfolio or being reprimanded was that he was a close relative.

Meanwhile, some of our political appointees were also not very savvy – either politically or diplomatically. A Sri Lankan UNICEF official based in the Bangladeshi capital of Dhaka told me about a visiting Sri Lankan official from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Rome.

As the usual gesture among Sri Lankans posted overseas, the UNICEF official arranged for a meeting between the Sri Lankan Ambassador, a political appointee, and the visiting FAO official.

At the meeting in the envoy’s office, the UNICEF official discovered the ambassador obviously had not done his homework: he was not only ignorant of what the FAO was all about but, worst of all, he did not even know what the acronym FAO stood for. During the course of the conversation, the envoy asked the FAO official what his area of specialisation was.

Told he was in charge of a division overseeing fisheries, the envoy’s eyes lit up, this time with a personal request: “I say, can you get me some Maldive fish?” Perhaps transmitted via the UN diplomatic pouch from FAO to Dhaka.

In the Sri Lankan diplomatic service there is never a dull moment. Or so it seems. There was the hilarious story of a newly-appointed ambassador, accredited to an Asian country. He downgraded his brother-in-law to the rank of a cook, in order to include him as a member of his staff so that the Foreign Ministry can pick up the tab for his travel and upkeep.

And then there was the widespread story of another envoy who took his mistress under the guise of a maid to a European capital — with the foreign ministry paying for her services, as she was on the embassy payroll.

But there were also exceptions to the sordid stories emerging from world capitals.

As one of Sri Lanka’s hot-shot criminal lawyers, Ambassador Daya Perera was not only gifted with oratorical skills but also a razor-sharp sense of humour. At the United Nations, where he had a post-legal career as Sri Lanka’s Permanent Representative (1988-1991), he had a field day unleashing both his skills with the force of a double-barreled shotgun.

Since journalists and diplomats are perpetually looking for inside stories, political gossip and breaking news, I built a strong working relationship with Daya during his tenure as Ambassador. When I was in his office one day, he dropped a file marked “Confidential” before me.

At first glance, it looked like a journalist’s dream because the file was expected to contain, not only Sri Lanka’s official stance on some of the politically sensitive issues, but also letters detailing the running battle he had with the then Foreign Secretary in Colombo.

Just when I thought I may have a series of journalistic scoops, he remarked in characteristic Sri Lankan idiom: “You bugger, you can read, but you cannot write”.

“Daya” I told him, “you are treating me like a eunuch in a Middle Eastern harem. I can see all what’s going on, but I cannot do anything myself.”

He laughed at that wise crack, and for a moment, felt i had upstaged him.

But in tempting me with the “Confidential” file, he was not only making a gesture symbolising our friendship but also refusing to betray the trust his government had placed on him as a senior high-ranking diplomat at the UN.

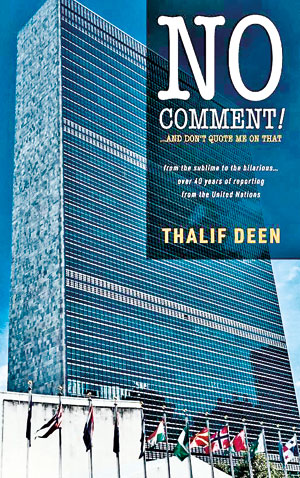

(The article is based on a recently-released book on the United Nations titled “No Comment and Don’t Quote Me on That”. Authored by Thalif Deen, a former UN staffer, a onetime Sri Lankan diplomat, and a veteran UN correspondent, the book is available on Amazon, and at the Vijitha Yapa bookshop. The link to Amazon USA via the author’s website follows: https://www.rodericgrigson.com/no-comment-by-thalif-deen/)