News

Elephants kill more farmers in fightback for land

A humble abode damaged by an elephant (file pic)

Pemadasa, a farmer in Gongangara, Buttala, was on his way to stand guard over his plot on Wednesday evening when he was suddenly attacked by a wild elephant on the Waguruwela Temple road.

The father of three was rushed to the local hospital and then to the Moneragala District General Hospital but died of his injuries the following morning.

Some two weeks earlier, 61-year-old Anura Gunaratne and a fellow farmer were trying to chase an elephant away from a night-time incursion into a chena farm near Okkampitiya in Moneragala when the animal struck back, killing him on the spot.

About 100 elephants have been killed since the start of this year

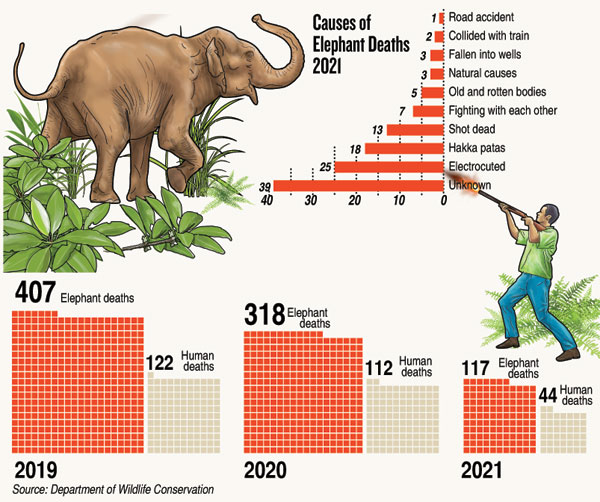

The two incidents bring to 44 the number of human lives lost in the unending conflict with elephants since the start of this year – and the cost to elephants is much greater, with possibly 100 killed by humans, partly due to an alarming increase in illegal cultivation in forests.

“This week’s news could be mundane to many of us who have been so conditioned to such deaths over decades but for rural villagers who live close to the jungles it is a living death,” conservationist Hemantha Vithanage said.

He mourned the loss of elephant life in the daily struggle for access to food and water as humans encroach into wilderness.

“The number of elephant deaths this year is sure to hit record levels as a result of illegal land-grabbing and habitat destruction,” Mr. Vithanage predicted.

“Decades of illegal clearing of thousands of acres of forest land, and erecting fences to deter elephants from using their age-old routes, has culminated in the human-elephant conflict the country sees today,” he observed.

Mr. Vithanage believes 60,000-80,000 hectares of forest have been razed for chena cultivation in the Monaragala District alone since the 1980s.

The extent of electrified fences in illegally-acquired forest lands had caused wild elephants seek alternative routes to migrate between Gal Oya, Yala, Kumana, Udawalawa and Lunugamwehera National Parks.

“Politicians encouraged poor farmers to live closer to the jungle. Some built houses for them inside reserves without any proper assessment of the suitability for such purpose, endangering both human and animal lives,” Mr. Vithanage said.

According to the Wildlife and Forest Conservation Ministry Secretary Somaratne Vidanapathirana, there have been 117 wild elephant deaths so far this year, only three of them natural deaths and seven others due to fighting between elephants.

Of the remaining 107 deaths, 39 are being investigated to determine causes but the rest – the bulk – were due to crimes by humans.

“The majority of the deaths are caused by human activities: shooting, electrocuting and ‘hakkapatas’ or explosive baits that blow up inside elephants’ mouths,” Mr. Vidanapathirana said.

Most of the elephant deaths were reported from the Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa districts and the Eastern Province.

“The main reason for the conflict is the limited amount of land for agriculture and consequent encroachment into elephant habitat,” Mr. Vidanapathirana noted.

“We have an action plan, with priority given to construction for electric fences around villages that are highly vulnerable to elephant attacks.”

The work involved reconstruction of about 1.500km of existing permanent fences. “We have had some setbacks due to the pandemic but will complete it before next year,” Mr. Vidanapathirana said confidently.

He said the ministry had implemented alternative projects such as planting of thorn-bushes around settlements and encouraging farmers to take up less invasive projects such as bee-keeping but these did not show a successful result as quickly as building electric fences did. “That is why the villagers are happy with these fences,” he said.

Conservationist Vithanage contends electric fences are the least effective mitigator of conflict as they are not based on scientific observations of elephant movement.

“There are virtually hundreds of kilometers of ad hoc electric fences erected by private individuals, sans any study, right across paths trod by elephants in the middle of jungles. These are illegal and aggravates the conflict,” he pointed out.

“In the Somawathiya and flood plains national parks there are a large number of enclosures, some for cattle.”

He said there was an alarming increase in illegal squatting inside national parks, sanctuaries and reservations, with the clear backing of politicians.

“Traditional elephant habitats are clearly disturbed, compelling these animals to come out into villages and into open conflict with farmers more often, even in broad daylight,” Mr. Vithanage pointed out.

“The villages inside parks should be removed and the people should be settled elsewhere if a lasting solution to be found,” he emphasised.

He also called for more wildlife officers to be recruited, saying the need to deploy large numbers on elephant management caused the neglect of other wildlife needs.

In 2019, 405 elephants were killed in Sri Lanka – the world’s highest toll that year – while 121 people were killed by elephants that year – the second-highest toll in the world.