News

Experts warn outright ban on fertilisers would cripple farmers and harvest

Norochcholai: A farmer using fertiliser sparingly on his crops. Pix by Hiran Priyankara

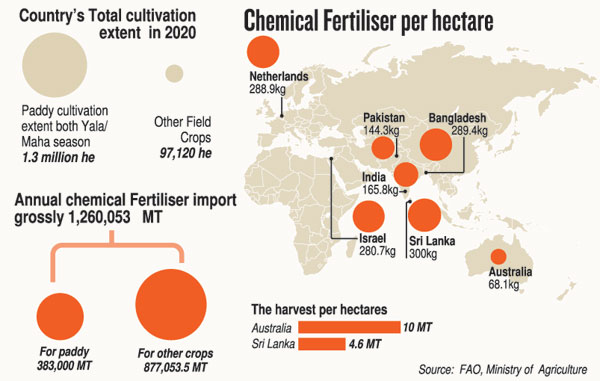

Rice production could drop by almost half in the next Maha season due to the outright ban on agrochemicals, a former top industry expert warned, as debt-ridden farmers pleaded for a phased cessation of fertiliser and agrochemical use.

Vegetable prices will increase towards the end of the year and the country’s rice production would be decreased by 30-50 per cent in the coming Maha season early next year leading to higher rice prices if the government imposed a total ban on fertiliser and pesticide imports, former Ceylon Chamber of Commerce Chairman Samantha Ranatunga, said.

Announcing a complete ban on agrochemicals on April 22, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa defended the move on grounds of adverse effects to human health through increasing toxicity of chemical-polluted groundwater and other water sources. “Lives are more valuable to me than a high yield,” a statement from his office said.

Mr. Ranatunga, who has three decades of experience in agriculture, pointed out that the price of rice had increased despite the bumper harvest of the last Maha season and excellent weather early this year.

“We had excellent weather, fertiliser, everything was good, but prices of paddy remained high,” he said. Assuming similar conditions and without the aid of chemical fertiliser, he predicted yield would be reduced by 30-50 per cent.

The government would have to pay for imports to fill he shortfall on top of paying farmers for the loss of yield from switching to organic fertiliser, Mr. Ranatunga said.

A farmers’ leader said most farmers have outstanding loan payments from various financial institutions and are frightened that higher costs and lower yields would push them further into the abyss.

They are calling for a relaxed phasing-out of chemical fertilisers and agrochemicals with guidance and state oversight.

“If farmers are to cultivate crops without fertiliser the yield is sure to be lower and farmers would be compelled to move out of farming,” W.P.D. Somaratne, a seasoned farmer in Saliyawewa, Kahatagasdigiliya, complained.

“We all know chemicals are bad. Yet, farmers don’t know how to use them. they do what agrochemical traders ask them to do and traders are in turn, advised by chemical companies,” he said, claiming that government agricultural officers had not advised farmers how to use chemicals.

“Most of the time, farmers overuse fertiliser and other chemicals. They use it right before the harvesting of vegetables. There is nobody to regulate or monitor the use of chemicals,” Mr. Somaratne said.

A farmers’ leader said most farmers have outstanding loan payments from various financial institutions and are frightened that higher costs and lower yields would push them further into the abyss. Pic by Jayaratne Wickramaarachchi

While speaking out against the ban on farm chemicals, Mr. Somaratne seemed to acknowledge the harm believed to be linked to extensive use of the substances.

“Whatever they do, farmers lose. Everybody will become ill with cancers or kidney diseases,” he said.

He stressed that ad hoc transition from chemical to organic cultivation could be disastrous and suggested a gradual shift, with intensive guidance by officials on how to control pests and on methods of making manure.

He also stressed the importance of introducing high-yielding indigenous seeds.

“Organic farming is arduous,” he explained. It made cultivation harder at every stage, from preparing soil to the harvest. Using chemical fertiliser was easier.

Organic farming meant more planning: “All adjoining fields should be cultivated simultaneously”, he said. Using nets to control pests was costly.

Young farmer Mohamed Arshad said there was a dearth of fertiliser in Nuwara Eliya, the heart of the country’s temperate vegetable-growing region, following the announcement of a total ban on fertiliser imports.

“Farmers here are already helpless without fertiliser,” he said. “The hybrid varieties of vegetables need fertiliser: without it, you can’t get a good harvest.”

He claimed the organic fertiliser available in the market was substandard and called upon the government to grant subsidies to buy manure in large quantities.

Potato farmer W.A. Meththananda said imported hybrid seed varieties of vegetables need more nutrients than organic fertiliser could provide. The country does not produce any hybrid seeds, “nor do we have any alternatives”, said Mr. Meththananda, who is head of the Community Seed Potato Farmers Association.

Like Mr. Arshad, he said fertiliser and other agrochemicals were out of stock in Nuwara Eliya, attributing this to hoarding by large-scale farmers.

“We can’t meet farmers’ demand,” agrochemical trader Mohan Pinnduwa of Agarapatana said. He and another agrochemical trader in Nuwara Eliya, W.M. Dhammika Rajapaksha, complained of empty shelves in their shops because of rush buying.

When the government announced the ban of chemical fertiliser, well-to-do-farmers bought sackloads, leaving nothing for ordinary farmers, Mr. Rajapaksha said.

“Those small-scale farmers need pesticides to start new cultivation of leeks, carrots and beetroot in a few weeks as snails would not leave any small vegetable plants unharmed,” he said. The snails could not be manually controlled, he asserted.

Mr. Pinnduwa said farmers in Nuwara Eliya depend on agrochemicals as the district received more rain than the dry zone,

The District Director of Agriculture in Nuwara Eliya, T.M.A.K.D. Tennakoon, while speaking of problems in moving to organic fertiliser, spoke plainly about the effect of decades of chemical spraying on soil.

“The soil here is dead due to use of excessive fertiliser and chemicals,” he said. “We need to revive it with organic fertiliser.”

He said low levels of nitrogen in organic fertiliser had to be addressed and pointed out that considerable labour was needed to produce this fertiliser in the quantities required by tea plantations in the area.

The climate of Nuwara Eliya was unsuitable for the processing of organic fertiliser noted the director.

Former Chamber of Commerce chairman Ranatunga said President Rajapaksa’s total ban was impractical. “Free fertiliser to no fertiliser at all is contradictory,” he said.

“Bring in the advanced organic farming methods now available in the world,’ he advocated, and claimed “we use the crudest form of fertiliser where there much more efficient and less harmful forms are available”.

His advice is: “Go for total organic in five years, 50 per cent in two years, with a structured and phased approach”.

He warned the government would face huge costs in implementing an immediate ban with paying farmers compensation for reduced yields and also for rice imports to fill shortfalls next year.

“The government is paying for the farmers for what is not produced instead of paying of what is produced and also for import to address a 30-50 per cent decrease in harvest,” he said.

He calculated this would amount to more than the fertiliser subsidy of Rs. 50 billion. The cost implication at a time of pandemic and balance of payment problems would amount to “policy failure”.

A ministry spokesman said Agricultural Ministry Secretary Rohana Pushpakumra was not in a position to comment.

Additional reporting by Shelton Hettiarachchi in Nuwara Eliya and Jayaratne Wickremaarachchi in Karuawalagaswewa