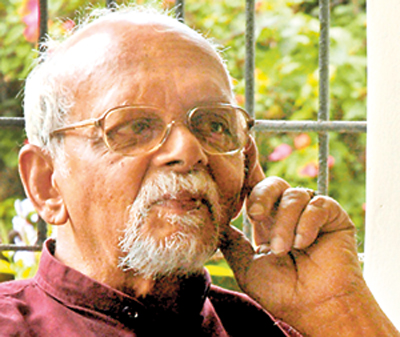

Learning from my father, five years after his passing

I was mingling with the audience at a poetry reading in Toronto, where I had been reading some of my new poems, when I was approached by an audience member. He asked me a question that I’ve encountered before in some form or another throughout my entire artistic and professional career… “Excuse me, are you by any chance related to Professor Ashley Halpé?” When I answered that I was his youngest daughter, the gentleman proceeded to tell me this story.

In 1970, he was a young student at Peradeniya, and had been in a literature course taught by my father. He had no intention of studying literature seriously, and when my father asked his students to memorize poems, he found the exercise tedious. One day, he brought this up with my father, asking him what earthly use a poem could ever have in the real world. My father answered that once a poem was folded into one’s deep memory, it could never be taken away. Our memory is always our freedom; it cannot be stolen by governments, nor ideologues. It is the last bastion of the self in circumstances when one is forced into otherness, robbed of will and agency.

In 1970, he was a young student at Peradeniya, and had been in a literature course taught by my father. He had no intention of studying literature seriously, and when my father asked his students to memorize poems, he found the exercise tedious. One day, he brought this up with my father, asking him what earthly use a poem could ever have in the real world. My father answered that once a poem was folded into one’s deep memory, it could never be taken away. Our memory is always our freedom; it cannot be stolen by governments, nor ideologues. It is the last bastion of the self in circumstances when one is forced into otherness, robbed of will and agency.

This young student would remember those words as the insurgency unfolded, and his friends disappeared into jail cells; he would remember them again as a young Tamil refugee, when he was forced to abandon his home and live in exile in Europe and then Canada. He had travelled an hour to come to my poetry reading to tell me this story, to remind me that, for my father, poetry was a quiet and yet wholly radical form of resistance that could never be stripped away.

I believe that my father found his politics in poetry. Not the kind of politics that toes party lines, but the kind of politics that persistently fights for social justice (before it was even called that). My father’s politics made him determined to give his students the access and power of the word, even when governments and systems would deny them that, even when he was forced to give his lectures in a “takarang” shed. It’s not surprising that among the many generations of his students, those who made it through the reorganization of the 70s became the fiercest intellectuals and activists, making their mark all over the world as scholars of literature, as artists and writers, as poets in their own right.

And even if his legacy is associated with the “kaduwa,” and the privilege that the English language affords the educated middle class, he was able to provoke and probe the hegemonies of his time through this colonizer’s language, whether it was through supporting writers like Lakdhas Wikkramasinha or Carl Muller as they emerged, or through staging subversive theatre productions that ended with him and his students being detained by censorship authorities. Perhaps as important to me, was his unflagging commitment to the “Wala” festival at Peradeniya, which brought luminaries like Sarachchandra and Henry Jayasena to an audience of thousands of hungry youngsters, who were as ready to hoot as they were to brave the rain and the leeches to sit in rapt silence as a child was pulled between two mothers in “Hunu Wataye Kathawa.” I was eight years old when I saw that production, and even as a child, I understood the difference between the force of greed and the radical, sacrificial power of love. This was my father’s legacy: one that was intimately tied to a time and a place, and to the kind of human being he strived to be.

As I pen these words in the midst of a pandemic that has shut down our world and forced us to pace the length and breadth of our homes like caged animals, I linger over the poems that are folded into my memory like a well-loved aerogramme from a father to a daughter. His voice returns to me:

[...]

I am knit into your tala, make

My words supple as Suramba’s bones,

Forged in a hunger for exactitude,

Bright as hill water, still as your lake,

Full in the mouth as ela-rounded stones,

Intense as sages in beatitude

—Ashley Halpé, from “Fall Poem, Looking Homeward” Homing and Other Poems (1993)