Two journeys and a book

In 2014, Ameena Hussein was at a Silk Routes Conference in the Maldives organized by the University of Iowa. She had been a 2005 Fellow of the University’s International Writing Programme. This six-day conference brought together writers, teachers, literary organizers and cultural entrepreneurs from different countries. In between discussions, a name kept cropping up: Ibn Battuta.

In 2014, Ameena Hussein was at a Silk Routes Conference in the Maldives organized by the University of Iowa. She had been a 2005 Fellow of the University’s International Writing Programme. This six-day conference brought together writers, teachers, literary organizers and cultural entrepreneurs from different countries. In between discussions, a name kept cropping up: Ibn Battuta.

The 14th century traveller-scholar had long fascinated Ameena. Though the Muslim Moroccan scholar and explorer’s name was referred to in passing he was a figure that lingered.

Ameena and her husband Sam Perera balance time between homes in Colombo and Puttalam. In 2015, Sam returned from a trip to the Puttalam town with a surprise – a photograph of an unusual street name: Ibn Battuta Street. Seeing the sign kindled an idea. Could she retrace his journey in Sri Lanka? “It was a mad idea,” reflects Ameena, laughing. But she set to work.

Ibn Battuta’s chapter detailing his experiences in Sri Lanka is easily accessible but a physical copy of The Rihla, his book on his voyages, took time to source. Ameena read and researched widely around Battuta, Sri Lankan history, colonial writings around Sri Lanka, academic work – anything and everything that she thought would be useful to put together a portrait of the man and vignettes of 14th century Sri Lanka. The research around the book was “a good form of Pandora’s box,” she says.

Ameena Hussein: A fascination with Battuta

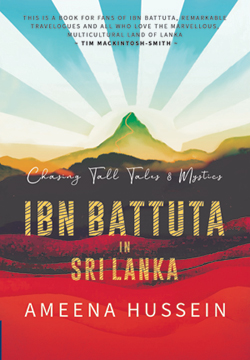

“What is most interesting for me as a Lankan is that he provides an insight into the hazy 14th century history of this country, before white colonialism made its entry in the 16th century…” writes Ameena in ‘Chasing Tall Tales & Mystics: Ibn Battuta in Sri Lanka’. Published in mid-October 2020, the book is the outcome of diving into this Pandora’s Box to parse a historical traveller from Sri Lankan cultural memory – memory that has accrued and shifted, or at times been erased according to the vagaries of geography and time.

Ameena writes that Battuta had a dramatic arrival to Sri Lanka. From the Maldives, where he had resided for nine months, he wanted to head to South India and then travel to Sri Lanka (Serendib) later. But inclement weather and a captain ill-equipped to navigate the wind and turbulent seas, saw his three-day journey stretched into nine and he tumbled into Sri Lanka instead.

The book states that Ibn Battuta probably came to Sri Lanka in early September, leaving in November. It weaves the past with the present, interspersing passages from The Rihla, historical anecdotes, chats with Sri Lankans about Battuta as well as Ameena’s own personal history – which proves to be a calling card within the Muslim community paving the way for candid conversations about the traveller. It also contains commentary around her experiences trying to retrace Battuta’s journey in Sri Lanka, including a pilgrimage to Adam’s Peak, and visits to certain towns.

To chart his route and stay on the island, Ameena bought multiple one-inch maps of specific areas from the Survey Department (her visits earned her the nickname ‘Sithiyama Miss’). She covered her living room with these maps, poring over them. For five years, Ibn Battuta dominated her life.

She quips that for five years, she was with two men – Sam and The Rihla placed by her pillow. “I was obsessed with the man. I would talk incessantly about him. My parents and Sam were the poor victims. They would time how long it took for me to say Ibn Battuta during conversations,” she laughs.

“I was fascinated by him, but he was also extremely flawed and I wanted to portray this in my book. He was a social climber, he meddled in politics, he wasn’t this likeable man all the time and he was very strict as a Muslim jurist,” she explains. “He was a contradiction in himself but he was observant – this, I would put to his training as an Islamic jurist. He was a complex man like all human beings.”

A challenge while researching was a lack of continuity, as names of places in Sri Lanka changed over time, and a dearth of translations across source material in English, Sinhala or Tamil prevents a deeper cross-pollination of resources. In the book, some of the gaps are offered to the reader through abstract possibilities which Ameena contextualizes and argues locating these among existing narratives and records. Battuta’s own accounts are sometimes scant on detail – a highlight of Battuta’s journey in Sri Lanka was the climbing of Adam’s Peak but we are told he is sparse in emotion in his descriptions of the experience.

A reluctance to be interviewed – the sight of a notebook and pen would clog free-flowing conversation – and navigating red tape bureaucracy while visiting certain sites were also small hurdles. But what Ameena remembers most is the generosity of people – many were generous in lending books and articles, sharing their time and knowledge and critiquing initial drafts of chapters. The travelling, writing and research took three years and she worked with Michael Meyler to edit the book over two years. The book is also slated to be translated into Sinhala soon.

Known as one-half of the duo behind the Perera Hussein Publishing House, not many would know she is an introvert, Ameena says – an admission that seems at odds with her exuberant public persona. “There are times when I need to retreat and that’s when I go to Puttalam. I don’t talk to anyone, I don’t see anyone. I can go for hours without talking. I can be quiet with Sam – so the three hours that we travel to Puttalam in the car, we don’t exchange a word. We just listen to music – loud music,” she says, simply.

Although well-known in Sri Lankan English writing circles, she remains hesitant to refer to herself as a writer. “I’m most comfortable as ‘Ameena Hussein – Publisher’ because that’s a defined job. I’m on sure ground as a publisher,” she reflects. “People can say you’re not a writer or they can say you’re a crappy writer or ….. all sorts of things. And I feel kind of shy to say I’m a writer because I feel I can always be better. A writer is a work in progress. With each book, I want to be better.”

For Ameena, writing is a compulsion and stories take time to ferment. “I write because I have things to say and I have stories in my head. And it’s when a story becomes too big to stay in my head that it gets onto the page,” she says. The idea for her novel Moon in the Water followed her for years and in Chasing Tall Tales & Mystics: Ibn Battuta in Sri Lankawe see a similar trajectory. The story of a Moroccan scholar and explorer clambers out of Ameena’s imagination, is fleshed out through his own narratives and historical and academic records and spills over onto paper, woven with the writer’s own personal history and travels around Sri Lanka.