Columns

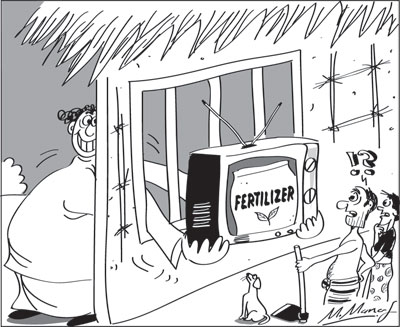

Fertiliser shift: when Haste makes more than waste

View(s):The current controversy over the ban on chemical fertiliser and pesticides and the consequences of this policy move remind me of the days long gone by when I used to write on agriculture for the Daily News.

This was way back in the second half of the 1960s when the then Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake would tour the country, promoting his passion — agriculture and irrigation — and I was not too far behind.

Later I used to accompany Hector Kobbekaduwa who was Agriculture Minister in the Sirima Bandaranaike government.

Later I used to accompany Hector Kobbekaduwa who was Agriculture Minister in the Sirima Bandaranaike government.

I wrote a weekly column on agriculture/development and relevant issues for a page the Daily News started once a week and for a monthly supplement. It inevitably led to criticisms of government policies and bureaucratic bungling.

One particular clash with the Ministry of Irrigation after a visit I made to Rajangana in Anuradhapura came to mind when I read of the government’s decision for a prompt ban on chemical fertilisers and wondered which of the masterminds that pass off as “intellectuals” was responsible for this.

What came to mind was a four-liner from the past:

“If little drops of water

And little drops of rain

Can fertilise an acre

Why not a bureaucrat’s brain”

In the course of the current controversy, somebody claimed that it was the self-proclaimed intellectuals of that group called “Viyathmaga” who promoted this ban. I have no idea whether this is true or not.

In the course of the current controversy, somebody claimed that it was the self-proclaimed intellectuals of that group called “Viyathmaga” who promoted this ban. I have no idea whether this is true or not.

If it is, then it is not too far from Viyathmaga to atharamaga as the months ahead will surely show when paddy yields drop, vegetables wither in chenas, tea plants struggle to survive, coconuts have to be imported and our rubber ceases to bounce like a deflated balloon and this country like no other will prove the blurb writer’s dream that this is indeed a country like no other.

Let one be clear on this. The policy decision to move away from chemical fertiliser to the organic, doubtless, has its merits, especially if one is expecting to produce a greener environment and contribute to sustaining the existing ecological system that is being increasingly destroyed by haphazard and unlawful deforestation, Illegal clearing of wetlands by avaricious man concerned not with improving our environment but with self-aggrandizement.

While conceding that turning to the use of organic fertiliser has its advantages, one does not rush into such policy changes with the indiscretion of bulls in China shops however much Chinese ware and the Yuan might be the flavour of the times.

Admittedly one learnt much about agriculture and irrigation and related issues from covering the district visits of Prime Minister Senanayake. But I already had practical knowledge from my school days at S. Thomas College, Gurutalawa where the college was located in some 50-odd acres of orchards, vegetable gardens and grazing fields for cattle and sheep in the salubrious hill country surrounded by undulating acres of pastureland and forests.

It was also a bird sanctuary for local and migratory birds. As bird watchers we were able to spot 54 varieties and identify them.

When agriculture was first introduced as a subject in the early 1950s for the then SSC examination, only a handful of students from S. Thomas, Royal College and Trinity College which also had farms but not as extensive as at Gurutalawa, sat for that subject.

As students following the agriculture course, we had to wake up 6am in the cold to wash the cattle and milk the cows which, believe me, was not an easy task in the early days with milk squirting our faces.

We had our individual vegetable plots that were attended to during school hours or whenever time was available. Those plots formed part of the practical exam for the SSC and were evaluated by external examiners. We also learnt to make butter, fruit cordials and jam from produce of the college farm.

Having seen the gathering interest in potato cultivation in the Welimada and Boralanda areas of the “hill country” and the few acres devoted to growing big onions which stood as proof that both could be grown here, I asked Premier Dudley Senanayake and Agriculture Minister MD Banda why we should not ban the import of potatoes and onions.

Prime Minister Senanayake was reluctant to do so fearing that if there was a crop failure or something untoward happened there would be a public uproar. Mr Banda was equally cautious wondering whether we would be able to meet the local demand saying that such a decision could not be rushed without considering the consequences.

That is the vital issue. Time is of the essence, which is one of the factors so well-articulated by my Thomian college-mate, good friend, a qualified agricultural economist and more Dr Nimal Sanderatne in his regular column in the Sunday Times two weeks back.

Space restrictions do not permit a recounting of the pertinent arguments against this sudden transmogrification from chemical to organic fertiliser not only in agriculture but also commercial crops as set out by Dr Sanderatne and my continued campaign with Minister Banda to ban the import of potatoes and onions in which I eventually succeeded, must await another occasion.

Those who claim to work for the upliftment of the peasantry and our poor might find it edifying if they read Dr Sanderatne’s column and the memorandum of the Sri Lanka Agricultural Economics Association (SAEA) that was forwarded to President Rajapaksa.

It carries an implied message especially to those who have entre’ to political power. If you do not know, learn, don’t mislead.

(Neville de Silva is a veteran

Sri Lankan journalist who was Assistant Editor of the Hong Kong Standard and worked for Gemini News Service in London. Later he was Deputy Chief-of-Mission in Bangkok and Deputy High Commissioner in London.)

Leave a Reply

Post Comment