News

COVID-19 and quarantine rules are keeping Lankan workers from going back abroad

The COVID situation in host countries is the main reason for the drop in the SLBFE registration of Sri Lankans going for foreign jobs

Sri Lankan migrant workers are reluctant to go back to work abroad. With rising COVID-19 rates and extreme quarantine requirements in destination countries the number of people registering with the Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment is low.

The registered migrant employment worker rate in Sri Lanka dropped from over two-hundred thousand people in 2019 to a little over fifty-thousand people by the end of 2020.

“The SLBFE needs to organise some motivational programmes or even propaganda to encourage more to take up the job opportunities,” said Arshad Ibrahim, Secretary of the Association of Licensed Foreign Employment Agencies.

At the same time Sri Lanka’s spike in COVID-19 patients and deaths which earned it its red list status among many countries is also a concern that is looming in the minds of industry stakeholders.

Saudi Arabia and Qatar are the only Gulf countries that are currently allowing Sri Lankan migrant workers to enter their local labor force. “The third wave has been quite tough on us,” said Mr. Ibrahim. While the demand for Sri Lankan labour had been untouched during the first wave, the current COVID-19 response strategy was under heavy scrutiny.

He noted that the spike in demand for local workers that happened during the country’s first wave, which was “well-handled”, was still existent to a certain extent. As the competitor markets like Bangladesh, Pakistan and India were shut down at the onset of the pandemic the demand for Sri Lankan workers was still high notwithstanding the countries that had red-listed Sri Lanka. “To date Saudi Arabia has hired about 35,000 more workers and Qatar has hired about 25,000 workers,” the secretary said. While the third wave may put a dent in things, job opportunities are still sufficient to absorb the Sri Lankan migrant worker base.

“We’re hoping that the vaccination programme will also be a boost right now,” he said pointing to the Labor Ministry’s recent vaccination programme announcement as their ray of hope.

Earlier this week the Labour Ministry confirmed the approval of the Pfizer vaccination of about 8000 migrant workers who were expecting to leave for 15 countries. Mass vaccinations for all the people who would be leaving were to be started in the first week of August according to Deputy General Manager and Spokesperson of the Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment, Mangala Randeniya. Migrant workers will also be given the specific vaccine approved by their destination country. Workers can register for their vaccine via a link on the SLBFE website and come on the designated day for their shot. 1000 of the vaccines were already prepared for use.

Mr. Randeniya also noted that online training programmes for migrant workers had started. To maintain the quality of Sri Lankan labour, the SLBFE had adopted virtual training techniques and assessment systems. The competency and performance of potential workers are done by assessors through videos or live sessions between them and the worker.

At present, about 300 people are being trained for housekeeping jobs while about 150 more people are getting training to become caregivers. The SLBFE is also planning on resuming their practical assessments with the workers through their centers islandwide. “We have about 17 centers all across Sri Lanka and soon we will be opening them under strict conditions to facilitate our practical training sessions,” he said.

At present, about 300 people are being trained for housekeeping jobs while about 150 more people are getting training to become caregivers. The SLBFE is also planning on resuming their practical assessments with the workers through their centers islandwide. “We have about 17 centers all across Sri Lanka and soon we will be opening them under strict conditions to facilitate our practical training sessions,” he said.

He also noted that the traditional markets of the Sri Lankan migrant labour remained open for them. Even though some were temporarily closed due to the current situation, once things settled the demand for local workers is expected to go back to normal. A new market had recently opened up in Japan for young people who sat for their Advanced Level (passing was unnecessary) and had an N4 level Japanese language qualification. The opening was for healthcare workers and professionals.

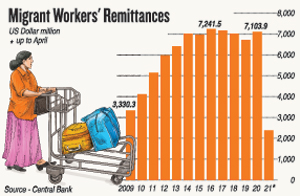

| Increase in migrant worker remittances through formal channels | |

| Incoming remittances from migrant workers were higher in 2020 than in 2019 due to an increased use of the traditional remitting processes.According to the Central Bank, migrant worker’s remittances rose from USD 6,717.2 million to USD 7,103.9 million from 2019 to 2020 despite marked reductions in migrant worker registrations and a significant number of returnees due to Covid-19. “People sent more money than usual home in general since families were having a hard time here and people also used the more formal methods for their transfers,” said Deputy General Manager and Spokesperson of the Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment, Mangala Randeniya. While recognised banking systems for the transfer of remittances from migrant workers to their families in Sri Lanka existed, a lot of workers used informal methods to get the money to their families. According to the spokesperson, this was partly because some workers did not have the necessary documentation and were employed abroad illegally. The main reason, however, was a lack of faith in the banking system, arising out of a lack of knowledge. “This is problematic to Sri Lanka since it results in us missing out on a lot of foreign exchange.” However, when the pandemic-hit economy struggled people’s faith in these informal routes took a hit. “So the people that could, began to rely on the formal banking channels to get their much needed money to their loved ones,” said Mr. Randeniya. Nonetheless Mr. Randeniya acknowledged that banks and the SLBFE had a duty to familiarise certain demographics of people with the banking systems and popularise its use. “We need grassroots level awareness and trust enhancing mechanisms.” The most common informal modes of remittance transferring are through ‘money brokers’ in the Hawala and Hundi system. The general concept is that the party taking the migrant worker’s earnings from the country of work coordinates with a partner here in Sri Lanka to give the equivalent Lankan Rupee value to the worker’s family at home. Hundi is an unconditional order in writing made by a person directing another to pay a certain sum of money to a person named in the order. The Hawala system, however, consists of a network of hawala brokers who transfer money without actually moving it which is where the system gets its name, hawala – “money transfer without money movement”. This system is handled by large operators and small business owners who engage in the system as a side hustle or moonlighting operation. However, a source that wished to remain anonymous, told the Sunday Times that as the economy worsens and people get more desperate for an extra buck, people’s trust in these informal methods deplete. Since the process is not completely legitimate workers can hardly pursue legal action in the event that the ‘money broker’ fails to hold up their end of the bargain. “It isn’t illegal for an individual to get money from someone and invest abroad, so it isn’t exactly illegal,” the spokesperson of the SLBFE clarified to the Sunday Times. It was more the exploiting of a loophole but an extremely unreliable method that could go very wrong. The SLBFE refers to these funds as ‘stagnated exchange’ and has difficulties quantifying the exchange lost to these routes since there’s rarely an official trail. The spokesperson also refrained from mentioning assumptions of the figure to avoid encouraging people into the informal transfer method. As for the undocumented migrant workers, what usually happens is that people go to work legally but fail to extend their contracts and renew their documentation. “We estimate that about 100,000 workers are currently working in the Middle East illegally, and 10,000 are in Lebanon without their documentation” he said. This often hinders the Bureau’s ability to troubleshoot even where the remittance of incompatible currencies is concerned. |