News

20 more occupations to be off limits for children

More new laws are being drafted to protect underaged children from potential abuse following the death of a 16-year-old domestic helper who had worked at former minister Rishad Bathiudeen’s Colombo residence.

More new laws are being drafted to protect underaged children from potential abuse following the death of a 16-year-old domestic helper who had worked at former minister Rishad Bathiudeen’s Colombo residence.

Last week, the Commissioner General of Labour, said that an amendment to the labour law of 1956 would be introduced to add 20 more occupations to the list of work considered hazardous to children.

The government in 1956 ratified the International Labor Organisation Convention categorising 51 work areas as hazardous for children.

The department said new laws would be introduced in the next two weeks.

Commissioner Prabath Chandrakeerthi said employment of children between the ages of 16 and 18 years as domestic helpers would be prohibited.

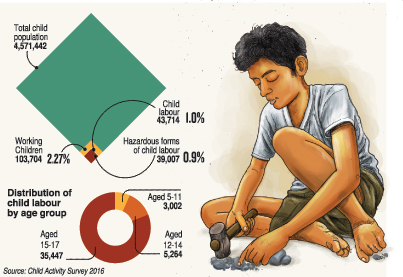

The Census and Statistics department (C&SD) in a survey in 2016, found 103,704 children were in paid and unpaid jobs, helping parents in cultivation and family business.

Among them, 59,990 children worked in paid jobs while 39,000 are in hazardous forms of child labour. Also 4,700 children are in involved in non-hazardous jobs.

A 1999 survey found 926,037 children were working. Ten years later, a 2008/09 survey showed the number had dropped to 557,599.

However, surprisingly 80% of working children had attended school in 2008/09 compared with 39 percent in 2016.

The drop in schooling was attributed to the long wait for ordinary level exam results during which time children find jobs and lose interest in further studies.

In January this year, the legal age a child can work was increased from 14 years to 16 years.

This had reduced the number of children working to 45,500 the Labour Department said.

Mr Chandrakeerthi said that mandatory education up to year 13 in schools has also contributed to the drop in the number of children working.

The survey also showed that 85% of children at work are from rural areas including from the districts of Colombo, Gampaha, Moneragala, Kurunegala and Batticaloa and work in the service sector operating plants and machinery in industries, tourism, transport, in construction and manufacturing businesses.

Most children were found to be making a little money for their parents who had little or no education and earned a pittance.

Ironically, this year has been declared as ‘Elimination of Child Labour 2021’ by the United Nations General Assembly.

Sri Lanka, which is working towards ‘zero tolerance’ with the aim to eliminate child labour by 2022 is a participant of ’8.7 Global Alliance’ .

The 8.7 Global Alliance is a forum of around 200 countries striving for a world where children only work for their dreams for a brighter future.

It advocates that ‘children work on their dreams and not in the fields’.

However, the incessant lockdowns imposed in the last two years because of the coronavirus disease pandemic has impoverished families, which have turned to their children to add to their family income, pushing children to give up on education.

An amendment to the labour law of 1956 would be introduced to add 20 more occupations to the list of work considered hazardous to children. Pic by Hiran Priyankara

Also the non-accessibility of online classes and lack of data coverage in many parts of rural Sri Lanka has frustrated children, who then give up on education.

Mr Chandrakeerthi refuted the claim that the young girl Ishalini’s death would be a damper on efforts to eliminate child labour.

He said it was a one off incident and will not damage government efforts.

Sri Lanka is a pathfinder to the ’8.7 Global Alliance’ and has set up a national steering committee of representatives from all stakeholders including the Education Ministry, the National Child Protection Authority, the Child Probation Department, the UNICEF and the ILO.

The committee, which last met last July, appointed a technical committee that was tasked with evaluating child labour in the country.

Meanwhile C&SD has agreed to begin a fresh survey on children in work in 2022. This, the Labour Department said will help update the data.

As a pilot project, the Labour Department is talking to the fisheries sector in the Gampaha district where several children have joined the trade.

Also it is working closely with Samurdhi officers who visit households to fill up forms of beneficiaries to gather information on working children.