News

Crushing pressure to excel drives kids to exit school in despair

Children from families working in the plantation sector are dropping out of school at an increasing rate to seek work due to crushing pressure to perform extraordinarily well at national exams.

Children from families working in the plantation sector are dropping out of school at an increasing rate to seek work due to crushing pressure to perform extraordinarily well at national exams.

These students are being pushed by teachers, principals, education zone and provincial directors to show good results at national exams so that these functionaries could earn pay increments and promotions, The Sunday Times has learned from a top teacher unionist sternly pointing the finger at his own profession.

The pressure in turn comes from the top – the Education Department.

In 2018, 20 children from Haputale went before the Human Rights Commission in Colombo claiming they had faced discrimination by not having been allowed to sit the Ordinary Level (O/L) national exams.

As well, 35 students from Broomfield Tamil Vidyalayam in Hatton were denied admission to sit the O/L exam the same year.

The teachers had deferred their exams for a year, referring them as weak students and demanding they sit the exam privately.

In many other instances children from hill country estate worker families were denied passage from primary to secondary school because they could not afford the funds demanded by school authorities for school development.

Although the push has eased following the Human Rights Commission’s ruling in favour of the students, the culture persists and is being enforced in subtle ways, the Ceylon Teachers Union (CTU) claims.

Other reasons for the dropout rate include children becoming disinterested in education, an unfavourable family environment to continue studies, parents divorced or separated, financial difficulties, chronic illnesses and disability.

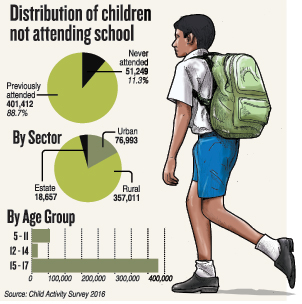

According to the Census Department’s Child Activity Survey 2016, an alarming 18,569 children between the ages of five to 17 in the estate sector had dropped out of school for one reason or other.

The monster of microfinancing that has entered the plantation sector in recent times has exacerbated the situation.

The CTU said many families who had taken loans under this scheme have been unable to repay the money and are turning to their children to salvage their fortunes.

Nuwara Eliya District CTU Secretary V. Indraselvan said many children in the hill country have given up education in search of employment to pay back family debts.

“The job brokers sneak in, enticing children with highly-paid jobs in Colombo during this time,” he said.

The children are taken to Colombo and employed in factories construction sites and as domestic maids for poor wages.

The domestic workers undergo untold hardship in households, being treated like slaves and subject to cruelty and sexual abuse.

The brokers are paid Rs. 5,000-10,000 per person. In order to earn more broker fees, they often shuffle the workers from one house to another.

The maid who died of burn injuries at former minister Rishard Bathiudeen’s residence was one such victim.

The COVID-19 pandemic has compounded the problem. Incessant school closures over 15 months and the absence of academic activities have caused many students to lose interest in education; they are now out looking for jobs.

“When children perform well, teachers and principals are celebrated for the excellent results. But what about those weak students who are not coached enough and eventually lose their education? Don’t they deserve better?” Mr. Indraselvan demanded.

“’The 15,000 teachers serving in the state schools in the plantation sector are answerable for their plight,” the teachers union leader charged.

On Thursday, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, at a discussion with the National Child Protection Authority (NCPA), the Labour Department and other stakeholders, directed grama sevaka niladharis to take a pivotal role in monitoring children in families in the estate sector.

They were asked to visit families with underage children and ascertain their whereabouts and schooling situation.

In January, the government raised the minimum age of compulsory schooling from 14 years to 16 years. For the purpose of employment, the definition of “young persons” was amended to be a person to have attained the age of 16 years but be under 18 years.

The NCPA said it was plain that its existing system of monitoring child labour was inadequate and it would examine alternate, accelerated programmes to prevent young children dropping out of school to find work.

The authority said it would execute a nationwide sustainable programne that would draw in officials working at grassroot levels with families with children under the age of 16.

Grama sevaka niladharis, agricultural officers, the police, midwives, Samurdhi officers, economic development officers and zonal education officers will be tasked with identify families where children are not attending classes or have dropped out of school to find work.

The focus will be on single-parent families including those where the parents are divorced or widowed, children of sex workers, drug-addicted parents, and beggars.

“Their problems will be determined and children helped to go back to schools,” an NCPA official said.