Sunday Times 2

Feather-ruffling reforms to break barriers over English

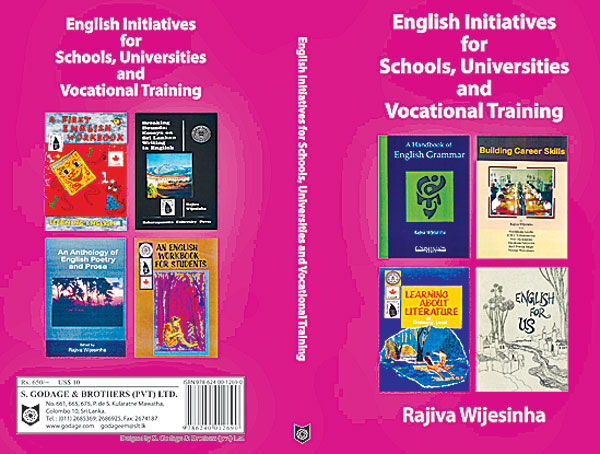

Book facts: English Initiatives for Schools, Universities & Vocational Training By Prof Rajiva Wijesinha Published by Godage & Brothers

An invitation to write a review for the new book by Rajiva gave me immense joy.

Seeing activity from Rajiva after many years, particularly on a topic so relevant in the context of English education, is a relief, since I had worried that he had decided to move into hibernation totally.

This book chronicles Rajiva’s experiences during much of his active academic, political and administrative career, i.e. as a university academic, an official working in the Ministry of Education and the National Institute of Education (NIE), as a Minister and finally as a Parliamentarian. In all these roles two things stand out: First, Rajiva’s efficiency and commitment towards anything he undertook were exceptional and unwavering. Second, he was brutally honest and transparent in dealings with colleagues irrespective of hierarchy, political or otherwise. His departure from public life in 2017, and stone-deaf silence since then, is now broken with this book.

My first-hand testimony to Rajiva’s work is related to the period during which he worked on English education at the Ministry. Those were heady days, laced with excitement and expectations. Landmark education reforms were underway, led by the then President.

On English education, and particularly on introducing English medium, Rajiva’s contribution was immense. The incredible speed with which he worked and the encouragement he gave me to set deadlines which I felt were hard to meet, but then was pleasantly surprised when they were actually met, bring back a flood of encouraging memories. He had the vision, understanding and the energy to roll out implementation within strict time-frames.

Since about 2000 when English medium education was introduced into junior secondary classes, and primary grade students were introduced to Activity Based Oral English, Rajiva’s role in spearheading both initiatives was significant. He describes details in the book. It appeared as though barriers were being broken finally, and that all children, irrespective of social class or means, would have the option of an education in English. Until then, this option was available only in international or certain private schools, and through tuition masters.

Together with all of this was the initiative President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunge was exceptionally passionate about, and that was to initiate a system where children of all communities and all religions were able to study in the same school, using the two national languages, as well as English as a link language (i.e. the Amity School project). These were historic efforts made towards forging national unity. They did not go down very well with most political and other leaders in government at the time. This book records some of the challenges we had to face.

Rajiva worked hard to invite reputed book publishers like Oxford University Press, Cambridge University Press and similar groups to join with the Ministry in partnership, when the multiple book option was proposed. This option would have enabled principals and students to choose the most suitable books out of a few that were recommended, instead of being compelled to use only the book prescribed by the NIE.

His enthusiasm and energy to enable preparation of good quality material for teachers, and to develop exciting books for students, are hard to forget. However, since text book writing and publishing had always been (and still is) the monopoly of the NIE & the Education Publications Department, Rajiva ended up ruffling many feathers. Navigating these challenges, whilst ensuring that the programmes continued, required skill, tact and some diplomacy from our part.

The book describes his role in the NIE, where he chaired the most important Academic Affairs Board – the nerve centre of that institution. He introduced reforms into curriculum design which added value and much needed soft skills. Digitised versions of secondary school curricula were published on the NIE website. This book gives extracts of some curriculum changes he initiated, such as ABOE or activity based oral English for Grades 1-2, English for Grades 6-10, and Life Competencies for Grades 6-10. Rajiva introduced new dimensions into a facility which had always held a conservative approach to any form of innovation. Again, many feathers were ruffled.

Rajiva had the knack of being hands-on, as I saw how he dealt with the four National Colleges of Education (NCOEs) mandated for teacher training in English. Similarly the remarkable work he did at Sabaragamuwa University. His undergraduate students and former trainees from the NCOEs used to speak of him glowingly.

After many years and after much political turmoil I next heard of Rajiva when he was tasked with the Ministry of Higher Education. Former colleagues in that institution praised him for the speed with which he worked during that short spell. I was not surprised, considering that speed was the hallmark of his implementation strategy – whilst again, ruffling feathers all the way.

If exceptional work-ethic was part of his DNA, so was ‘feather ruffling’.

This book gives an array of anecdotal experiences that Rajiva encountered during his multiple assignments, and would be informative to those who’d wish to work in those sectors.

‘Mavericks’ like Rajiva are a rare breed. A razor-sharp mind, keen intellect and genuine interest to give his best with passion and zest, are rarer traits. Having such people working in Sri Lankan government institutions which are at most times riddled with politicization, servility, bureaucratization, and corruption – is almost a dream. Only visionary government leaders and those with integrity would want to fulfil such a dream.

If that ever happens I do hope they’d remember to invite Rajiva Wijesinha to join their team.

(The writer is a former editor

of The Sunday Island,

The Island and consultant editor of the Sunday Leader)