Sunday Times 2

Lanka’s pre-2015 human rights discourse: A personal narrative

I was requested to read and comment on his latest work by Prof. Rajiva Wijesinha at the beginning of this month. Having being involved off and on for close upon four decades with human rights, United Nations mechanisms in Geneva, as the President of the Inter-Parliamentary Union’s Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians as well as being closely interested in the field of rights as a subject on a policy level and in practical measures to promote and protect rights in Sri Lanka, I was naturally interested in this commentary.

Prof. Wijesinha, in his book, focuses broadly on a seven-year period. His book is also descriptive of personal experience of his travels for leisure and engagement with the liberal movement. In sum, it is a deeply personal narrative, rich with individual vignettes, critical assessment and first-hand knowledge of the operation of national governance mechanisms and interactions with international and inter-governmental organisations and non-governmental institutions and agencies.

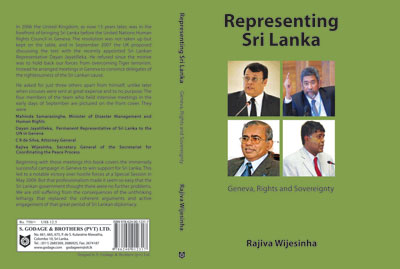

| Book facts; Representing Sri Lanka: Geneva, Rights and Sovereignty By Prof. Rajiva Wijesinha Published by S. Godage, Colombo; 2021 | |

The book’s narrative span ends just before the sea change in national politics with the election of early 2015 and the complete change of tack by the government of the day in Geneva in September of that year. Prior to that initial change of January 2015, there are several events and developments that provide context to the observations made by Prof. Wijesinha relating to the seven-year period under review.

In the 21st century alone, the Ceasefire Agreement (CFA 2002), the Boxing Day tsunami of 2004, the election of President Mahinda Rajapaksa in 2005, the Mavil Aru incident (2006), the military defeats of LTTE terrorism in the east (2007) and the north (2009) and the massive efforts at relief, resettlement, reconstruction, rehabilitation and reintegration and the (arguably) ongoing efforts at reconciliation, provide a rich and engaging tapestry depicting human tragedy, economic and social challenges and institutional upheavals.

The post 2016-challenges are outside the scope of the book. Added to this is the unceasing effort of a significant segment of the Sri Lankan expatriate Tamil diaspora who have integrated fully into the social fabric of certain Western nations since 1956. They now influence government policy, media coverage of Sri Lanka and socio-cultural life in these host countries. Some of the three generations of migrants, refugees and their descendants bear profound ill-will toward our country. So much for context.

When I was a young diplomat in Geneva in the 1980s, I had first-hand experience of this burgeoning malefic influence. What Prof. Wijesinha outlines is the hardening of attitudes among officials and policymakers who have been influenced by various geopolitical and other domestic drivers in their own countries. Constructive engagement with these forces and officials must therefore be nuanced and fine-tuned to garner the best outcomes for Sri Lanka.

Under my stewardship, we pursued such engagement. On the humanitarian front during the armed conflict, we forged a one-of-a-kind mechanism that brought together government, international stakeholders, national and international NGO institutions – CCHA (the consultative committee on humanitarian assistance). We launched initiatives aimed at comprehensive reviews of the domestic human rights situation through two successive UPR (Universal Periodic Review) processes before the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC). We formulated and monitored the National Human Rights Action Plan, which dovetailed and coalesced with the reconciliation effort; we engaged with UN Special Procedure Mechanisms and shared our experience with the Council. The government engaged with UN Treaty Bodies and reporting mechanisms. All in a spirit of open engagement. I acknowledge the support of my Consultant, Nishan Muthukrishna, and our human rights teams who worked on these matters during this period.

We believed that combative, didactic and theoretical approaches must be eschewed in favour of recognition that Sri Lanka is a small island nation vulnerable to the vagaries of international political fortune. An unfortunate reality is the near destruction of the G-77 and the NAM as spheres of significant influence in the modern era in favour of a unipolar world that does not cater primarily to the needs of the global south. The alliances such as that creditably achieved in May 2009 proved momentary, ephemeral and fleeting. That said, our success was a high-water mark. We saw a diminution of collective influence in this regard with the reengagement of leading global players at the UNHRC from that time on. It was for this reason that, as Minister for Human Rights and Special Envoy of the President on Human Rights, I repeatedly requested that the UNHRC should not be politicised and go the way of its predecessor – the UN Human Rights Commission. This was a recurring theme in my statements to the Council over time.

As to Prof. Wijesinha’s observations as to individuals and particular incidents, their causes and ensuing impacts, those perceptions are uniquely his. Suffice it to say that none of us actors during that period were without fault or weakness. As Queen Elizabeth II was memorably reported as saying in March this year: “recollections may vary”.

(Mahinda Samarasinghe, MP,

was former Minister of Disaster Management and Human Rights.

He is also Special Envoy of the President on Human Rights.)