Sal, the forgotten one

Birth of the Buddha: Frieze from Ghandara

The Sal tree (Shorea robusta) like its more celebrated counterpart the Bo tree (Ficus religiosa) is known to be closely associated with Buddhism. How the Bo sapling – a branch of the Bo tree under which the Buddha gained Enlightenment in Bodh Gaya was introduced to this country is also well known. It was around 288 BC that the emissary of the Mauryan Emperor Asoka – his daughter Theri Sanghamitta, carried it on a hazardous journey across hostile territory over thousands of miles of land and sea to Anuradhapura. That is one of the earliest documented episodes in the science and technique of introduction of a non-native species – an event both botanically and culturally to be celebrated.

The Sri Mahabodhi in Anuradhapura is the oldest recorded tree in the world and duly venerated.

Of the Sal tree, there are at least four references in the Mahavamsa. But when this tree native to the Himalayan foothills, was first introduced to Sri Lanka remains a mystery.

A few years ago, a small, exquisitely carved plaque was unearthed during the archaeological excavations in the vicinity of the Jetawanaramaya. The plaque bore a carving depicting Queen Maya, accompanied by two female attendants on a visit to her grandfather’s kingdom just prior to giving birth to Gautama Buddha in a Sal grove. Could this be the site where the first Sal tree was planted?

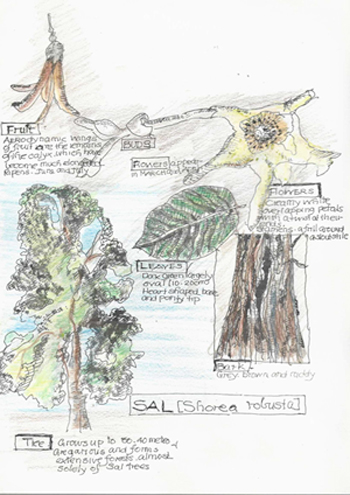

Sal tree

The Sal in Buddhist mythology is associated with the Buddha all throughout his life. Not only recording his birth but right throughout his years as a savant wandering over Northern India many of his sermons were given in Sal groves.

Even as his life was ebbing away, the Buddha is said to have summoned his main disciple Ananda just before his parinirvana and made his final request “Ananda, please prepare a bed for me between the twin Sal trees, with its head to the north. I am tired, and will lie down.”

To adopt a such a far-seeing environmental approach by the Buddha was hardly surprising. Long before he enunciated his philosophy of Buddhism, there existed a cult of tree worship in Northern India and Nepal and both the Sal and the Bo were among 60 other plants which were deemed sacred.

The Sal tree is prominently figured in sculptured friezes in several principal religious sites associated with the life of the Buddha such as Lumbini, Sanchi, Bahrut and Bodh Gaya. They are replete with representation of the Sal tree signifying its importance as a floral decoration in Buddhist art.

One of the most well documented is in the Sanchi dagoba complex. Over the Eastern gateway, on the two columns flanking the three tiered archways and 20 feet above the ground female figures are represented . The figures represent a Yakshini grasping an overhead branch of a flowering Sal tree, her feet firmly balanced against the roots and trunk which art historians denote as ‘salabhanjika’ or the “sal tree maidens”.

It is a decorative element which recurs in Hindu and Buddhist sculpture in Indian architectural and sculptural decoration over several centuries.

The exquisitely carved plaque unearthed in the vicinity of Jetawanaramaya

The lack of inclusion of the Sal tree in our Botanical literature is puzzling. The Sal does not appear in Alexander Moon’s Catalogue of Exotic Plants growing in Ceylon (1824), nor in the work of George Henry Thwaites’ Enumeration Plantarum Zeylanica (1864), or in the monumental five-volume work – A Handbook of the Flora of Ceylon (1893-1900) by Henry Trimen and Joseph Dalton Hooker. Other less important plants such as guava, passion fruit, coffee, rubber, tea, cocoa and numerous exotic plants have been given prominence.

Moreover, we are unaware whether saplings taken from the original Sal were transferred to other holy sites- as was the practice with the first introduced Bo tree. The present specimens of Sal found in the temples in the Kandy and Ratnapura districts were obtained from the Peradeniya Botanical Gardens nursery in the 1970s and ’80s.

A likely explanation for its disappearance was that it was supplanted by a totally insignificant species, the Cannonball tree (Couroupita gulanesis) native to Peru that was introduced to the Gardens in Peradeniya in 1881 and later distributed as tree for large gardens and as a roadside plant. Easily recognizable with its nauseous scent and globular fruit, the Cannonball’s true habitat is Peru from where it was introduced by the staff of the Peradeniya Botanical Gardens in 1880.

As this Peruvian tree proliferated all over Sri Lanka, even the name Sal was hijacked and soon came to be used to designate the Cannonball tree.

For centuries the Sal has been one of the most dominant and useful trees because of its multiple uses and many by-products (see box story), but sadly in Sri Lanka it is little seen.

Once wider spread, its distribution is restricted and it is fast becoming a rare species even in Central India where deforestation is a major issue. Sal as a unique forest tree with all its botanical, artistic, cultural, religious and economic significance is in retreat- at risk of being altogether erased from history.

| It’s multifaceted too | |

Sketch of Sal tree by Ismeth Raheem The Sal unlike the Bo is not only one of religious significance -every part of the tree has been proved to have multiple uses. Although in most of Central India, Teak is the preferred timber as the best hard wood, Sal comes a close second. It has proved to be an ideal substitute for the construction of domestic and religious buildings as well as houses and temples. Some of the better-known examples of temple architecture in the Kathmandu Valley display intricate carvings of rafters and columns utilizing Sal timber. Other by-products of the Sal include the resin, seed oil, bark and leaves. Resin from the Sal tree is used as an astringent in Ayurvedic medicine, another extract is used to caulk boats and small sailing crafts.In Hindu religious ceremonies, the extracted liquid is often burned as incense. Sal seeds and fruit are a source of lamp oil and vegetable fat. The oil extracted from the seeds and refined is used as cooking oil and also as an ingredient in making chocolate. |