Sunday Times 2

When Taliban ministers refused to face female Sri Lankan UN officials

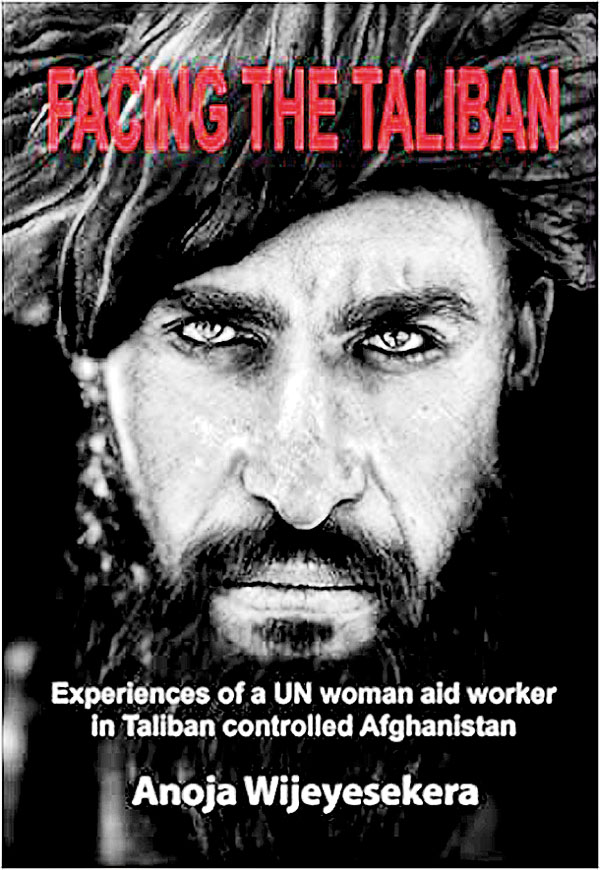

In this picture taken on September 23, 2021, Taliban members pray on the banks of a river in Kandahar. (Photo by Bulent KILIC / AFP)

UNITED NATIONS (IPS) – When the Taliban ruled Afghanistan during 1996-2001, the United Nations was engaged in a losing battle fighting for women’s rights.

And that battle was occasionally led by two senior Sri Lankan female officials, one of them who also provided humanitarian assistance inside unfriendly Taliban territory.

Radhika Coomaraswamy, a former UN Under-Secretary-General, who travelled around the world as Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women (1994-2003), recounted an uncomfortable eye-to-back – not an eye-to-eye — meeting she had with a Taliban official.

“When I met the Foreign Minister”, she told me last week, “We sat side by side on two distant chairs and he would not look at me. I kept putting my face in the line of his vision and he slowly turned his back.

“My bodyguard then leaned over and told me what should have been obvious: that he will not set eyes on me.”

“And when I met the Minister of Justice, I asked him about domestic violence and he told me that Afghan women were well brought up, and they did not attack their husbands,” said Coomaraswamy, one of the third ranking officials in the UN hierarchy, next to the Secretary-General and the Deputy Secretary-General.

In her book 'Facing the Taliban', Anoja Wijeyesekera recounts her experience of working with the Taliban

Meanwhile, when Anoja Wijeyesekera, received her new UNICEF assignment in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan back in 1997, her appointment letter arrived with a “survival manual” and chilling instructions: write your last will before leaving home.

A former UNICEF Resident Project Officer (1997-1999) in Jalalabad and later in Kabul (1999-2001), she recounted an identical anecdote similar to Coomaraswamy’s.

“When I first went to Afghanistan in 1997, as the UNICEF Resident Project Officer in Jalalabad, the Taliban refused to look at me, as I happened to be a woman. At meetings, which were all- male events, they would look away from me with an expression of total disgust and would keep their heads turned away from me, when speaking to me,” she recounted.

“After a couple of months of this icy reception, which I considered to be a farcical comedy, they gradually thawed and even shook my hand, spoke in English, and became friendly.”

“And I said to my staff that perhaps the Taliban thought that I had turned into a man!” she added jokingly.

According to a report in the New York Times last week, during the first years of Taliban rule, from 1996 to 2001, women were forbidden to work outside the home or even to leave the house without a male guardian.

“They could not attend school, and faced public flogging if they were found to have violated morality rules, like one requiring that they be fully covered.”

At a fund-raiser last week for humanitarian aid to Afghanistan, which generated more than $1 billion in pledges, Martin Griffiths, the UN Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, said when he met with Taliban officials recently in Kabul, he received assurances — in writing.

The message read: “We have made it clear in all public forums that we are committed to all rights of women, rights of minorities and principles of freedom of expression in the light of religion and culture, therefore we once again reiterate our commitment and will gradually take concrete steps with the help of the international community.”

But the lingering question is whether the Taliban government will honour these commitments – particularly, judging by its past track record.

Last month, UN Human Rights High Commissioner Michelle Bachelet said that in many areas under effective Taliban control, credible reports speak of serious violations of international humanitarian law and human rights abuses such as summary executions of civilians, restrictions on the rights of women, including their right to move freely and girls’ right to attend schools, recruitment of child soldiers, and more.

Meanwhile, asked about her personal experiences during her tenure in Afghanistan, UNICEF”s Wijeyesekera, described the Taliban as a motley group of fighters, mullahs and other fringe elements of society including drop outs, bandits, criminals and bigots that have come together under the umbrella term “Taliban” which means students.

They are supposed to be students of Islam and by their own definition, she pointed out, they are students and not graduates or professors. This is revealing as many of the foot soldiers are semi-literate but well versed in the art of guerrilla warfare.

“Their brand of Islam is totally opposed to the accepted version of Islam that is taught in universities and other places of genuine learning,” said Wijeyesekera, in an interview last week.

“As you know the madrasas of Pakistan were established with the support of the CIA to train mujahideen fighters to defeat the Russians. I have seen the Nebraska curriculum, which is explained in my book (“Facing the Taliban,” available on Amazon) which was a tool to brainwash poor children into becoming cannon fodder on the battle field.”

During her time in Afghanistan, she said, some Talibs holding positions in government were more educated. However, many were Mullahs who were completely closed to the outside world, having only been taught in a Madrasa.

The Minister for the Prevention of Vice and Promotion of Virtue [V&V] named Torabi was a one- eyed, one-legged fighter whose only occupation was beating people, mostly women, she said.

His Ministry was in charge of floggings, beheadings, amputations and stonings. If the newly created Ministry with that name, is headed by a similar person, the result would be similar, she added.

Despite these absolutely horrific practices, conducted by their own “government”, “I have to say that at a personal and sub-national level, the more educated departmental heads were relatively flexible, as they understood the benefits of UNICEF programmes for the children and women of Afghanistan.”

As time progressed, one of the most ruthless and die-hard Taliban leaders — the Minister of Health, developed an understanding with me, regarding the implementation of UNICEF programmes, as he could see the benefits of those programmes.

“Thus, I would say that although ‘policy’ could be one thing, practices could vary depending on the location and the particular Talib in question.”

Asked about other senior female UN officials, she said there were women heading other UN agencies in Afghanistan, including the head of UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) both in Jalalabad and Kabul. Also, in Jalalabad the head of the office of the World Health Organization (WHO) was a woman.

Meanwhile, the UN may keep posting women to Afghanistan — at least to ensure the validity of Taliban’s claims on women rights.