Now online; portals into our past through the lens of radical activists

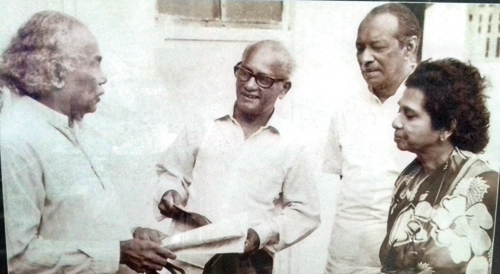

Peace mission 1987: Fr. Tissa Balasuriya, Vijaya Dharmawardhena, Charles Abeysekara and Bernadeen Silva

The online archive of Dissidents and Activists in Sri Lanka offers narratives from the 1960s to 1990s by radical activists from the south of Sri Lanka. The ephermeralia and documents digitized in the archive are from personal collections, institutional libraries and collectives scattered around Sri Lanka. The nearly 600 documents in the archives interrogate rival ethno-nationalisms and explore alternative political and development projects through the lenses of Marxism, Christian socialism, and feminism and more.

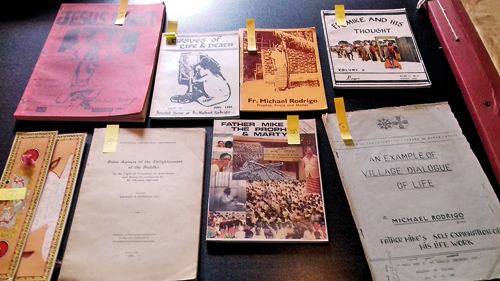

For instance, a part of the archive contains academic work and literature by Fr. Michael Rodrigo known for his work and activism in Alukalavita, Buttala with farmers and workers in the lower-Uva region. He was a strong critic of the acquisition of the Pelwatte Sugar Plantation by a multinational company. In a 2019 article, Kanya D’Almeida writes of how the farming community in Alukalavita relied on chena cultivation and struggled against the economic effects of the Sugar Plantation Corporation, environmental devastation caused by deforestation, the introduction of chemical fertilizer and the political apathy of the ruling classes to their plight. For years, Fr. Rodrigo immersed himself in the community and sought to understand their struggles while advocating for political and social transformation and being vocal about the ramifications of the environmental changes unfolding in Sri Lanka.

On November 10, 1987, Fr. Rodrigo was shot dead while celebrating evening mass. The archive contain scans of tea-coloured newspaper clippings announcing his death, follow-up articles about the lack of investigation and eulogies and leaflets memorializing him. “Catholic priest killed at prayer in Buttala church” reads a news clipping of the Daily News, sandwiched between a Shakespeare quote, a bomb blast and details of a court martial following the attempted murder of Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi by a Sri Lankan Navy officer.

The online archive of Dissidents and Activists in Sri Lanka from the 1960s to 1990s was launched earlier this year and is centred on the theme of dissent, documenting the activity of Sri Lankan activists within a particular generation who challenged the existing political and social status quo. The archive is a collaboration between the owners and custodians of the collections, the American Institute for Lankan Studies (AILS), the University of Edinburgh, Princeton University Library, and the South Asia Open Archives.

The collection is divided along three sections. One is a collection of left-wing political and civil rights pamphlets and booklets from the 1960s to the 1990s authored and published by former left-wing political parties, trade union movements, and civil rights movements. Another consists of writings from the Sri Lankan Liberation Theology movement in the late 20th century that drew from the liberation theology and religious movements centred in Latin America, which sought to reclaim and reinterpret the role of faith in addressing social inequities and the pursuit of social justice through political and civic involvement. The third section features materials from the Women’s Education and Research Centre’s (WERC) library. This includes WERC’s journal Nivedini, newsletter Pravahini as well as flyers related to women’s resistance movements and women’s rights awareness programmes of the late 20th century.

Fr. Michael Rodrigo archive ready for digitization.

“While Southern archives and libraries didn’t come under the same kind of threats and duress that the Northern archives did, there is a tendency in the post-war period to forget the activism and alternative voices, whose ideas are still very relevant,” says Crystal Baines, Associate Director of Programing and Digitization – AILS, Colombo which was tasked with the digitization. “This archive helps to brush up people’s memories. For people who remember these activists and collectives, it reminds them of the work that was done. And also there is an entire generation coming up that knows nothing about these people. I think this archive helps to carry a certain collective consciousness of the late 20th century forward, without us forgetting that there was this grassroots activism that went beyond political affiliations.”

The archive was produced as part of a larger project titled A Comparative Anthropology of Conscience, Ethics and Human Rights, directed by Prof Tobias Kelly (University of Edinburgh). The researchers working on the Sri Lankan component of the project are: Dr Harini Amarasuriya (Open University Sri Lanka), Dr Sidharthan Maunaguru (National University of Singapore), and Prof Jonathan Spencer (University of Edinburgh).

A notable feature of the archive is that it is free for anyone with internet access.

“I think it will allow the general public – especially students and researchers interested in this subject to access hitherto unavailable sources about an extremely significant time in our modern history. This is really important because we need to have an understanding about our past to analyse and comprehend our present. Also to figure out what happens next. We also need to be able to understand the past from many different perspectives and not just the dominant, mainstream perspective. These are issues that should be part of our everyday conversations – not just confined to niche audiences. So I am so happy that this archive is open access,” said Dr Harini Amarasuriya.

The project also resulted in multiple learnings for the collaborators.

“First, we have realized the value of individual collections of endangered historical material. For a variety of reasons, they have not approached state institutions or other organizations that could help them preserve the material in a better way. Building trust with the custodians and other stakeholders is a careful balancing act that needs to be conducted carefully. This is the second learning we have gained. Thirdly, by trialling smaller digitization projects, we have learned that it is a highly technical process which includes individuals with many different skills. It is not as simple as taking a scanner and digitizing, which is what most people have in mind. The process involves inventory/record keeping, prepping the documents, the technical process of digitizing using different scanners, coding, naming and labelling the scans, etc. It is a very labour intensive process,” said Dr Vagisha Gunasekara, Executive Consultant -AILS.

The digitization and easy access has been especially helpful at a time when mobility and travel is restricted.

“I get a lot of calls from others appreciating it (the archive),” says Sister Milburga, one of the custodians of some of the material in the collection. “People call me to say that it is a big help and they find it useful.”

Signing an MoU with Satyodaya Kandy. Pics courtesy AILS and the online archive of Dissidents and Activists in Sri Lanka

Digital archives also offer a mode of preservation to counter any deterioration caused by mould and insects such as silverfish. To date, the burning of the Jaffna Library is one of the deepest cultural wounds in the country. Efforts such as the Noolaham Digital Archive and Aavanaham Multimedia Library arose as a result of this destruction and erasure, digitally preserving knowledge bases and the cultural heritage of Sri Lankan Tamil speaking communities.

In as much as digital archives offer a host of benefits, it feels important to also take into account the fragility of digital records – tech obsolescence is a factor to contend with. While there are scattered individual efforts to digitally archive ephemera and alternate narratives, institutional infrastructure and funding offer considerable advantage as keeping digital archives usable requires regular effort, maintenance and commitment.

In ‘Pathways of the Left in Sri Lanka’, Ajith Samaranayake writing on ‘The Left and Mass Media in the 20th Century’ points out that the Left in Sri Lanka have used newspapers, leaflets, pamphlets, booklets and related literature as tools and instruments of communications as well as “weapons of intra-party fighting”. A challenge in compiling the metadata, explains Crystal, was contending with this genre of writing amidst the political context of the time.

“Most of the items in this collection are pamphlets and leaflets – we were dealing with a genre of writing which people used back then to very quickly get the word out or to create awareness about something. We now take that for granted because we have social media.

“Because of the urgency of the moment and rushed nature these pamphlets were put out, the author would sometimes forget to put the date or where he or she was writing from. Then there were instances where we noticed where the author was deliberately withholding the date or location or they wouldn’t even put their name on it, because they want to maintain anonymity because they’re talking about something controversial, and they don’t want the police to come and pick them up,” explains Crystal of how the archives give a glimpse of particular undercurrents at a point in time.

Many parts of the archive bear reflection for our current zeitgeist. Reading the first code of ethics for gender representation in Sri Lanka’s electronic media published by WERC, one wonders how much has changed – “Avoid portraying women performing household tasks while the rest of the family relaxes” reads a guideline for formulating advertising policy .

Understandably, there are limitations and critical engagement is required with the material. Timelines are sometimes approximations. Gendered language and stereotypes can be discerned in some of the writing. The archive is not exhaustive. There are omissions due to censorship, privacy issues and gaps in preservation.

“If people have a good understanding of history, you can think of the future properly and understand what happens to a society historically, what went wrong, particularly. Archives preserve some of the important things in history. They are important to remind people of the historical memory of society, a country. That is the role of an archive,” reflected a custodian who wished to remain anonymous.

Perhaps ultimately these portals into the past offer reminders, as Rev. Paul Caspersz writes in a document, that “We have to search for a saner and just world.”

The Archive of Dissidents and Activists in Sri Lanka (1960s to 1990s) can be viewed at: https://dpul.princeton.edu/sae_sri_lanka_dissidents