FTA: A painful choice for Sri Lanka

View(s):

Night scene of Ho Chi Minh City by Saigon river, Vietnam. Picture by Huynh Luu Duc Toan.

Vietnam has attracted a lot of attention in the recent past due to its fast track record of achieving growth. It was followed by the trade liberalisation policy reforms in the country which began with the so-called Doi Moi policy in the later 1980s. Much of the success can be attributed to the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) inflows and the resulting export growth.

In 1990, Vietnam and Sri Lanka both had similar levels of merchandise exports amounting to US$2 billion. The difference was that the export mix of Vietnam was still dominated by traditional agricultural export crops such as rice and coffee, Sri Lanka had already achieved over half of its exports coming from the industrial sector. In 2020, that is 30 years later, Sri Lanka supplies $10 billion worth exports and, Vietnam over $280 billion in exports. Vietnam’s industrial exports account for about 85 percent of total exports with the main export items including machinery, telephones, computers, electronics, footwear, garments, beddings, and prefab buildings.

Vietnam was much poorer than Sri Lanka; in 1990, its per capita GDP was $95, compared with $465 in Sri Lanka. But today, Vietnam has come closer to Sri Lanka’s per capita GDP level, indicating that it can also surpass Sri Lanka very soon.

International integration

The success story of Vietnam is primarily due to its international integration which was supported by its own ‘unilateral’ policy reforms which continued to-date, and its strategic international integration through ‘regional’ and ‘bilateral’ free trade agreements (FTAs). Soon after initiating unilateral policy reforms since the late 1980s, Vietnam joined the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1995. ASEAN which had existed since 1967 now comprises 10 Southeast Asian nations: Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand,

and Vietnam.

I wonder whether Vietnam, which was a “closed economy’ with an import substitution policy just 10 years ago, complained about Singapore’s free trade policy or the economic supremacy in the region; in fact, Sri Lanka did so and complained that it’s easier for Singapore to enter into a FTA with Sri Lanka, but it’s difficult for Sri Lanka to enter into that FTA with Singapore. As a result, the Singapore – Sri Lanka FTA is now under review, even after signing it!

I wonder whether Vietnam, which was a “closed economy’ with an import substitution policy just 10 years ago, complained about Singapore’s free trade policy or the economic supremacy in the region; in fact, Sri Lanka did so and complained that it’s easier for Singapore to enter into a FTA with Sri Lanka, but it’s difficult for Sri Lanka to enter into that FTA with Singapore. As a result, the Singapore – Sri Lanka FTA is now under review, even after signing it!

In fact, Vietnam’s decision to enter the ASEAN opened for it a massive growing regional economy with over $3,000 billion GDP (2020) and an expanding regional market with 650 million population. Having access to such a lucrative market is only one side of the story, which makes no sense if Vietnam had not continued with policy reforms to generate trade from within the country; and Vietnam did it with continuity in unilateral policy reform process.

European markets

Today, Vietnam is a member state for 15 regional and bilateral FTAs in the world, including ASEAN as well as ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA). Out of these, six of the FTAs have been the agreements between ASEAN and another partner – Australia and New Zealand, China, Hong Kong, Japan, India and South Korea. Vietnam, being a member of the ASEAN, automatically enters into the FTAs of the ASEAN.

AFTA is ASEAN’s own free trade area agreement entered in 2010 aimed at eliminating 99 percent of tariff lines and at creating a single market. The most recent strategic move that Vietnam adopted was to enter FTAs with the European Union (EU) signed in 2019 and with the United Kingdom (UK) signed in 2020. The Vietnam – EU FTA has provided a massive upper-income market of 27 EU member states which account for average $35,660 per capita income and 447 million people.

The UK, at the time of its departure from the EU – Brexit -, was enthusiastic in entering the FTAs with as many countries as possible in order to mitigate the adverse effects of leaving the EU. In fact, as of now the UK has entered into 37 FTAs with many countries including those developing countries in Asia (including Vietnam), Africa and Latin America.

Abandoned reforms

Abandoned reforms

We in Sri Lanka have a proven record of our “inability” to be as bold as Vietnam so we have chosen to remain “isolated” as much as possible. While Sri Lanka’s FTA with Singapore is now on hold, the proposed FTAs with countries such as China, Thailand, and South Korea have dragged on for many years. After all, Sri Lanka never thought of entering FTAs with the EU or the UK or any other developed countries with high-income markets. If Sri Lanka had taken that initiative, it would have had the opportunity even to give up the GSP+ scheme comfortably.

It may be a valid question to ask why is it difficult for

Sri Lanka to enter into FTAs? The main issue is that it is painful for a country that has given up its “unilateral” policy reform process to enter the FTAs with those countries which have carried out policy reforms. For the past 25 years, Sri Lanka has not embarked upon policy reforms, but it had adopted many changes in policy in an ad-hoc and piecemeal manner.

All ad-hoc and piecemeal policy changes, which you often came to know when you get up in the morning, had done little for the country’s future prosperity. They only serve individual interests so that you would see some businesses flourish overnight from nowhere, while some businesses collapse from the business world; some individuals become rich overnight, while some individuals struggle to survive.

If it is in this context that we have to enter the FTAs with countries which have adopted a continuous reform process, it is painful and politically unsustainable. The reason is it looks easier for the partner country to enter the free trade, because they have come a long way towards free trade; they can easily eliminate their 3 percent or 5 percent tariff and enter the FTA. But for a country having tariffs, para-tariffs and non-tariff barriers, it is a whole different story!

Painful integration

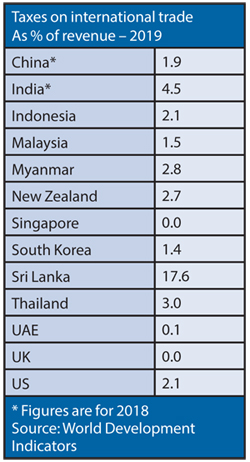

It is hilarious to see that, after being one of the forerunners in policy reforms in Asia as far back as 1977, Sri Lanka’s taxes on international trade account for nearly 18 percent of the government revenue (2019, before the COVID pandemic), compared with 4.5 in India, 2 percent in China, 1.5 percent in Malaysia, 3 percent in Myanmar and 3 percent in Thailand.

Obviously, it is a difficult and painful choice for Sri Lanka so that it is politically correct to keep the country as poor as it is. Moreover, it may not be difficult for Sri Lanka to go along with “poorer” countries entering the FTAs, because usually we find higher tariffs and import controls in poor countries in Asia and Africa.

What about Sri Lanka’s FTA with India? Someone could ask a valid question. While the Indo-Lanka FTA had been manipulated subsequently by both sides, it was obvious that Sri Lanka failed to use it’s potential market advantage. Again, the problem is more at home than with the neighbour; FTA unveiled the opportunity, but access to it depends on local capabilities.

Although India has offered a big market of over 1 billion people, Sri Lanka never generated enough trade volume to cater to that big market or attracted enough FDI to produce in

Sri Lanka aiming at the Indian market. Instead, today India itself has become an attractive investment destination, catering to $50 billion FDI, which is expected to rise to over $120 billion by 2025. Thus, Sri Lanka had lost the opportunity unveiled by the Indo-Lanka FTA, because the country didn’t clean up the policy mess at home and prepare for it.

(The writer is a Professor of Economics at the University of Colombo and can be reached at sirimal@econ.cmb.ac.lk

and follow on Twitter @SirimalAshoka).