“In debt we trust”

View(s):

Sri Lanka's Central Bank Governor (left) with his Omani counterpart during a recent trip to Oman to seek funding support.

This week at a television discussion, the interviewer asked me an interesting question: “What is your view on selling Sri Lanka’s valuable ‘resources’ to foreigners – particularly, stakes of public enterprises and pieces of the country’s valuable land?” I knew that the question had some relevance to the current discussions on selling such assets to foreign companies.

It was just two weeks ago I wrote in this column about the sale of the100 percent stake of Air India to the Tata group. It was a massive public enterprise run by the Indian government for 68 years. Someone might say that Tata is not a foreign company. It’s great that India also has big private companies of its own which can afford to spend US$ 2.4 billion and buy Air India which has a fleet of over 130 commercial aircrafts running all over the world and many other assets. Another would say that it was like selling such a massive public enterprise for a song, because the airlines’ unpaid bills alone amounted to $2 billion and accumulated losses to $9.5 billion.

Although Tata group among other competitors won the bid to buy it this time, the Indian government has tried selling it even 20 years ago. And at that time the foreigners came to buy it – Singapore Airlines, British Airways and the German Lufthansa. The Indian government enforced a condition requiring the buyer to partner with an Indian company. When the conditions were unfavourable to foreign investors, they all withdrew from the deal. If there was no local buyer and if the conditions were favourable enough, then Air India would have been acquired by a foreign buyer.

Selling assets

A couple of weeks ago, we were aware of a number of Fundamental Rights (FR) petitions filed by various lobbying groups including some political parties against the Cabinet decision to sell a 40 percent government stake of a thermal power plant to a US-based company. Further, this week we again heard the news about a possible trade union action at the CEB against the government move, interrupting electricity supply in the country.

Having heard the news, the university (Colombo) too postponed its on-going online examinations. Many others must have done the same thing in an uncertain business environment of the country, putting their scheduled work on hold causing millions and billions of rupees lost to the economy.

The question that I mentioned at the beginning is interesting because it was the popular way of presenting an unpopular move by the government. But we should know that the same question can be termed as either “selling Sri Lanka’s assets” to foreigners or “investing in Sri Lanka’s assets” by foreigners.

The question that I mentioned at the beginning is interesting because it was the popular way of presenting an unpopular move by the government. But we should know that the same question can be termed as either “selling Sri Lanka’s assets” to foreigners or “investing in Sri Lanka’s assets” by foreigners.

In our political set up, it is politically correct to say that “our assets would not be sold to foreigners” because, perhaps, it would bring the politicians to power. However, the same thing can be said as “foreign investment in our assets would not be permitted” in this country. But it is a weak statement

to generate enough cheering in

the electorate.

There is, however, a difference between two types of foreign direct investment (FDI) flows as autonomous FDI and accommodative FDI. While we should not treat both in the same way, we can even produce misleading foreign investment statistics if we add them together. An outstanding feature of autonomous FDI is “new additions” to the country’s capital stock by foreign entities, while accommodative FDI is merely a transfer of existing assets of the country’s capital stock to a foreign party. The latter has not created anything new by adding new capital, though it may be an incentive to attract the former – autonomous FDI too adding to the capital stock.

FDI as a short-cut

The stock of capital of a country refers to man-made durable assets that are used in production and business. How fast a country can build its stock of capital is an important determinant of production and business contributing to growth, income, employment and exports. FDI is a “short-cut” to build the stock of capital, because in general there is no shortage of FDI flows in the world. In fact, over the past 30 years, FDI has increased six-times and turned increasingly towards developing countries in Asia. The issue in question is, however, that FDI – particularly autonomous FDI – does not flow to every country, but to selected locations only.

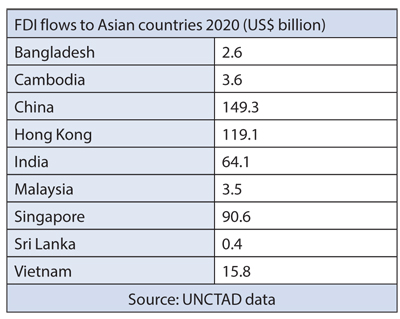

In the midst of the COVID pandemic issue, world FDI flows declined by one-third in 2020, but still accounted for nearly one trillion dollars, compared to 1.5 trillion in the previous year. While China, Hong Kong, Singapore and India were the largest FDI-recipient countries in Asia, Vietnam also secured a remarkable share amounting to $15.8 billion. Cambodia and Malaysia attracted about $3.5 billion, each. While Bangladesh received $2.6 billion, Sri Lanka attracted only $0.4 billion.

In the midst of the COVID pandemic issue, world FDI flows declined by one-third in 2020, but still accounted for nearly one trillion dollars, compared to 1.5 trillion in the previous year. While China, Hong Kong, Singapore and India were the largest FDI-recipient countries in Asia, Vietnam also secured a remarkable share amounting to $15.8 billion. Cambodia and Malaysia attracted about $3.5 billion, each. While Bangladesh received $2.6 billion, Sri Lanka attracted only $0.4 billion.

One could argue that China and India are big economies with a growing middle class from its over one billion population. True; however, Singapore and Hong Kong are the smallest economies in the list, still attracting big FDI flows competing well with big FDI-recipient countries. The secret is that these two city-states have overcome their smallness by establishing their input and output markets globally.

Foreign exchange crisis

One of the important features of the countries attracting FDI is the fact that they have established big markets for both inputs and output through unilateral policy reforms as well as regional or bilateral trade agreements. In addition, they have a business environment conducive to attract investment in which policies and regulations are simple, predictable and consistent and, where there is law and order protecting investors and investments.

The countries which do not have bigger input and output markets and conducive business environments try to attract FDI through various tax incentives and ambiguous deals. The biggest issue is that they struggle with foreign exchange crises because without FDI these countries do not have the two main sources of long-term foreign exchange supply – FDI flow itself and, its resulting export growth.

In the absence of FDI flows and resulting exports, these countries must borrow foreign exchange. They borrow to build up foreign exchange reserves and to maintain the exchange rate. They borrow to import their needs and to invest in infrastructure. Then,

they borrow to pay previous borrowings with interest. Their credit worthiness is downgraded, they go around with a begging bowl to borrow from other countries.

Against investment

Here is the crux of the matter: We don’t resort to trade union actions against foreign borrowing, but we do that against foreign investment. We don’t file FR petitions against foreign borrowing even by mortgaging our children, but we do that against foreign investment. We don’t ask the question about how are we going to pay foreign borrowing without export growth and FDI growth, but we do question about foreign investment.

After all, we don’t want to make the changes in our policy environment in order to make it attractive to foreign investment. But we are okay, if our governments make our country eligible to attract more borrowings. It’s because in debt we trust, not in investment. An additional thought is that in the midst of multiple sinister movements (by governments on deals of this nature), it’s difficult to judge even the genuine ones.

(The writer is a Professor of Economics at the University of Colombo and can be reached at sirimal@econ.cmb.ac.lk and follow on Twitter @SirimalAshoka).