News

Hundreds of thousands of child marriages take place annually due to loopholes in the system

“I told them I would kill myself.”

Now 20, she was 17-years-old when they tried to wed her to a 30-year-old man. She threatened her parents with suicide, she told the Sunday Times. She knew she was entitled to an education, to university, and she resorted to the most desperate threat to hold on to her future.

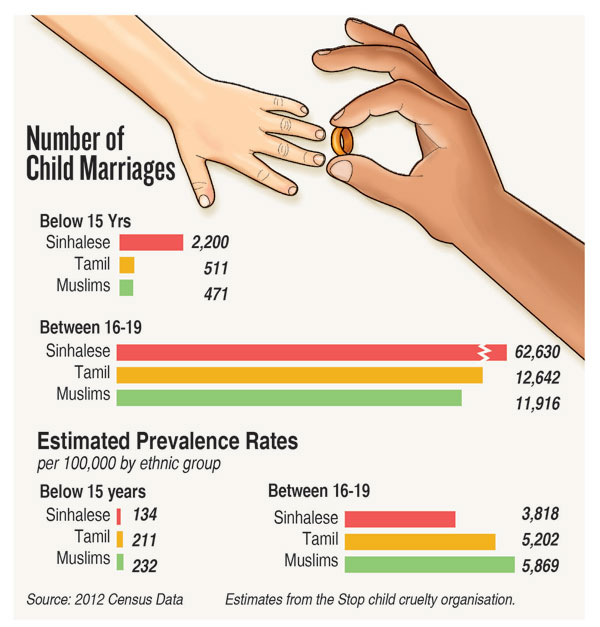

Loopholes in the marriage registration system and personal laws like the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act (MMDA) are leaving thousands of children vulnerable each year. The most recent count of the Census and Statistics Department dated 2012 recorded over 100,000 child marriages (including widows and divorcee counts). Activists contend the real figures are higher..

Specific provisions in the MMDA keep many child marriages off the official record, said Shreen Saroor, the founding member of the Mannar Women’s Development Federation and co-founder of the Women’s Action Network. Section 16 states that marriage without official registration is permitted. Most unions take place inside mosques and the registrar often does not even see the bride as a male guardian signs the certificate. “There is zero scrutiny beyond that of family members,” she said.

Specific provisions in the MMDA keep many child marriages off the official record, said Shreen Saroor, the founding member of the Mannar Women’s Development Federation and co-founder of the Women’s Action Network. Section 16 states that marriage without official registration is permitted. Most unions take place inside mosques and the registrar often does not even see the bride as a male guardian signs the certificate. “There is zero scrutiny beyond that of family members,” she said.

Ms. Saroor has been an avid activist in the MMDA reformists lobby. A key demand is the setting of the minimum age of marriage to 18. Technically, the minimum age of marriage under the MMDA is zero. Section 23 permits the marriage of a girl below the age of 12 provided that a Quazi judge signs off on it.

While there have been no reports of marriages this young, Ms Saroor pointed out reform will resolve all concerning grey areas the law now has. As it stands, the MMDA leaves young victims of sexual abuse especially vulnerable–the habit of marrying sufferers off to their abusers was a rising concern, especially in the East where her groundwork was mainly based. Consent to marry was a vital part of Islamic Law. The practical reality, however, was that young children had no say even when facing a lifetime of rape.

The Muslim community supported setting the minimum age of marriage at 18, claimed Sheikh M Arkam Nooramith, General Secretary of the All Ceylon Jamiyyathul Ulama (ACJU), the leading Islamic theologian community organisation and an active participant in the MMDA reforms debate. The issue, however, was that the age of consent and the age of marriage were inconsistent with each other.

In Islamic law, the purpose of marriage is sexual relations as all other relationships are permitted outside the frames of marriage. Sheikh Nooramith said, because, while an age of marriage is not specified in Islamic law, adulthood is believed to be attained at puberty.

The community’s suggestion, according to Sheikh Nooramith, is that 18 be the minimum age of marriage and age of consent, but that marriage after 16 be permissible under special circumstances and strict regulations.

“Islam does not promote child marriage in any way, this is merely propaganda aimed to make the Muslim community look barbaric,” said Sheikh Nooramith. And it was problematic that Sri Lanka did not even have a consistent definition of what a “child” is.

The National Child Protection Authority (NCPA) has submitted a Cabinet paper defining “child” as being any person under the age of 18 across all laws under Sri Lanka’s international obligations. “We showcase our standards with our laws,” stressed Sanjeewani Abeykoon, Director of Law Enforcement.

With the exception of marriage under personal laws, sexual interactions with a girl under 16 are considered statutory rape as a child’s consent is not valid. Under the General Marriage Law, registrars who married people under 18 have their licences revoked.

And despite the law explicitly setting the minimum age of marriage for non-Muslims at 18, the 2012 census showed that tens of thousands of children from these communities are also still married off annually.

A Sunday Times investigation found that lack of clarity in the Marriage Ordinance hampered the will and authority of the Marriage Registrars to completely eliminate child marriages.

“In most instances, people hand in fake identification,” said N. C. Vithanage, former Registrar General. As there is no centralised data source for Marriage Registrars to verify identification documents, their hands are tied.

The SMART systems that record national identity information were only introduced in 2017. This significantly reduced forgeries and there is an easy checking system. But old identity cards are still valid and easy to fake, he said.

Alarmingly, Marriage Registrars were not empowered to insist on further verification should they suspect that an under-age marriage was about to take place. “Identification of any kind is the only real requirement and there are so many options that can easily be faked,” Mr Vithanage said.

While Section 15 of the General Marriage Ordinance sets the minimum age of marriage at 18, Registrars do not believe this empowers them to make further inquiries or stop a marriage they suspect was “forbidden” by law. The absence of a verification system further weakened their position–they could not refuse a marriage licence based on uncorroborated suspicions.

But Attorney-at-Law Ermiza Tegal said this seems to be an instance of statutory misinterpretation. The minimum age of marriage outlined in the ordinance gives the Act’s enforcers an ancillary right to take any action necessary to uphold it. This includes a stay of marriage on suspicion the one or both of the parties are underage. However, the law does not in its most cardinal terms empower them to do more than ask for the birth certificate.

“It really depends on how you interpret it,” Ms Tegal noted, adding that another interpretation–the one that is technically closest to Parliament’s intent–is that unless the Act specifically forbids the refusal of a marriage licence, unless further verification takes place, the registrars are empowered to conduct any further investigation necessary.

Because of the absence of a good mechanism to do the checking, Registrars will have little incentive to run a thorough investigation and to go through the lengthy processes of letter writing to verify the information.

Meanwhile, the social drivers of child marriage in Sri Lanka were economic necessity, teenage pregnancy, and patriarchal stereotypes. A common train of thought was the rush to “settle” girls down before they got “too old” and “less desirable”.

“Some communities still see daughters as burdens,” Ms Saroor said, adding that most parents begin looking for suitable matches when the children are 16 and just completing their O/Levels. “These extremely patriarchal stereotypes scare parents into thinking that their daughters’ value expires by the time they’re 19.” This is worsened by misinformation that, the younger the girl is, the easier it is to give birth.

The community also conformed to patriarchal notions that a girl’s life ends when she has sex, Ms Saroor said. “There is a twisted attachment of a family’s honour to their young daughter’s virginity,” she explained. “So even in well-to-do families, the patriarchal idea that giving a virgin daughter in marriage is everything runs strong.”

The fear of young women having pre-marital sex was a driving force behind the community’s aversion to setting the minimum age of marriage at 18. “The idea that if you have sex, you must pay for it for the rest of your life is robbing our community of our young women,” Ms Saroor warned.

Coercing girls into marriages after unplanned pregnancies inadvertently showed that the life of the embryo was more important than the living and breathing young girl. “You will be raped, domestically abused, and financially dependent for the rest of your life,” she lamented.

Ms. Saroor has received death threats and suffered repeated personal attacks over her activism. Her organisation has offered safe houses and shelters for young girls to give birth in before they resume their schooling. She supports the view that adequate sex education and knowledge about contraception are vital to ending teenage pregnancy.

Tush Wickramanayaka, founder chairperson of the Stop Child Cruelty Trust, agrees. Making contraception freely available and responsible sexual and reproductive education are vital. “Giving a condom is NOT a licence to copulate or impregnate,” she insisted.

Where teenage pregnancies do occur, existing options need bettering. Adoption and establishment of functional foster care agencies have not yet been adequately explored. “Stigmas have to be broken and the opportunity to go to school should not be taken away from the young mothers,” Dr Wickramanayaka said.

The economic impact of depriving a community’s girls of secondary and tertiary education will have immeasurable generational impact. “How is marrying your child off for money any different from pimping them out?” she questioned. The mental, physical and sexual complications of underage marriage are not unknown. “A personal law that overpowers the common law cannot exist,” said Dr. Tush, who was against the idea of any exceptions being granted even in the event that 18 is set as the minimum age.

The implications of child marriage go beyond gender equality. When a girl child is educated, maternal mortalities reduce, life expectancy of children beyond five years increases, and diseases are reduced. Research shows that even a 0.3% increase in the GDP is possible.

“Child marriage is an issue both prompted by economic vulnerability and perpetuates economic vulnerability,” Ms Tegal defined.

Whilst it affects every ethnic community in Sri Lanka, Muslim children, unlike other children in Sri Lanka are not protected by law, campaigners say. Legally recognising a child is an important part of securing the full a range of rights for a child, and ensuring it has the best possible opportunity for physical, emotional and economic security and well-being.