Enduring symbol of Colombo University

College House: Many chapters in its long history

The majestic College House down Thurstan Road – a whimsical marriage between an English country house and a Maharajah’s haveli with its conical roofs, turrets and slender carved wooden columns, is for the historian a relic of a bygone age. Originally called ‘Regina Walawwa’, in time the house would be renamed College House and become the icon of the Colombo University.

Built by Thomas Henry Arthur de Soysa for his wife, she would sadly never preside over the mansion or walk down its sweeping staircase, as she died before the building’s completion in 1912.

It was in 2017 that Sandagomi Coperahewa, Chair Professor of Sinhala at the University of Colombo, suggested to the then Vice Chancellor Lakshman Dissanayake, a volume on this building that has seen so much, from weddings so grand London’s society pages would write about the bride’s trousseau and the wedding cake, to being home to the island’s very first university.

Co-edited by Prof. Coperahewa and Dr. Shravika Damunupola Amarasekara of the English Department, ‘College House: The Cradle of Sri Lanka’s University Education’ is a handsome coffee table volume thick with previously unpublished images from the building’s past.

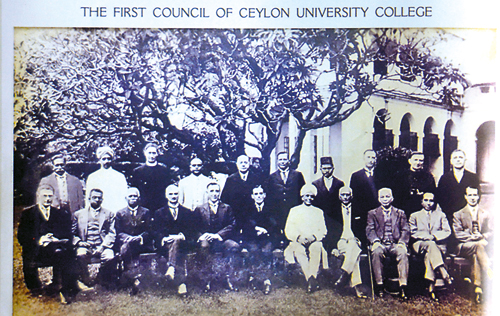

The first council of Ceylon University College

The book is divided into four parts; the first dealing with when it was a family home; the second when it was the University College and the University of Ceylon; the third when it became the administrative hub of the University of Colombo and the fourth dealing with its architecture.

In the first part is included a cameo of the world that gave birth to Regina Walawwa, written by the architectural historian Prof. Anoma Pieris, herself of the de Soysa family. Arthur and his brothers wanted not to be ensconced in replicas of the English stately home like their father, the famous philanthropist Sir Charles Henry de Soysa. It was, as Anoma shows, a high point of the Karave elite trying their hand at indigenisation. Regina herself wore the newly fashionable sari (albeit with fan, gloves, brooches, frills and court shoes) and their mansions had names like walawwa and Lakshmigiri.

The de Soysas, especially Anoma’s father L.S.D. Pieris, opened up the family archives generously, revealing such emblematic photos as Regina’s funeral where the family keeps a stiff upper lip around the body, and Regina’s daughter Violet’s epoch-making wedding, the bride in sari, with orange blossom and white heather in her wreath in the fashion of English royal brides,

Arthur and Regina de Soysa

and celebrated for seven days in keeping with eastern pomp.

Prof. Coperahewa says that collating pictures and putting together the saga of College House took years. Dr. Amarasekara adds that particularly elusive was the period after 1952 and the shift to Peradeniya. Old university magazines provided a regular record but these required frequent visits to the Peradeniya University Library, whither they had all been taken when the University of Ceylon shifted to Peradeniya in 1952.

The book maps the beginnings of our academia; how in 1921, E.B. Denham bought the Walawwa from an Arthur de Soysa much depleted financially, and began the ‘Ceylon University College’ with just 12 teachers.

From thereon begins a magnificent saga, of how both the arts and the sciences flourished just like the gargantuan maara trees down Thurstan Road with pioneering local orientalists like G.P. Malalasekere, the Rev. Suriyagoda Sumangala, M.D. Ratnasuriya and Ediriweera Sarachchandra as bilingual pundits who set enviable standards; and ‘western’ scholars like Lyn Ludowyk and S. A. Pakeman.

Dr. Siyath Gunewardene has contributed a chapter on ‘The Ceylon University College Contribution to Science and Mathematics’.

The University College became the University of Ceylon in 1942, with Ivor Jennings, the charismatic Cambridge man, who then ‘led the way to Peradeniya’, thus putting an end to “the Colombo chapter of the University of Ceylon”- “the end of an era and the time of new beginnings”.

Dr. Shravika Damunupola Amarasekara

In the third part of the book, it is at the ‘dowagerhood’ of the College House we look where it has become the administrative hub of the brand new University of Colombo.

The sole later addition to College House is the new Senate Hall, seamlessly merged with the original building thanks to architect Ashley de Vos, in 2002.

Prof. Sandagomi Coperahewa

Though Ashley is dubious about these “salad (s) of widely differing parts of buildings” created by the Victorian and Edwardian nouveaux – “a hotchpotch of ideas never holistic but fused together using the best of materials” – he was most scrupulous about preserving what he calls “an important contributory phase in the chain of evolution of the architectural typology in Sri Lanka.”

While the initial idea was to demolish outhouses and sacrifice the meda midula (inner courtyard) to make place for the new hall, Ashley opted to have the Senate Hall placed above the outhouse to the north.

The book is also interspersed with reminiscences of people who had known these corridors intimately – from Premasara Epasinghe who grew up there to former registrars and secretaries to the VC.

The editors are grateful to Chamini Kulathunga for research assistance, also Panduka de Silva for the photography and Malaka Lalanajeewa for the design and illustrations; both beautifully capturing the leafy campus and the vintage air of this protected heritage building now over a century old.

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.