In love with her city, Johannesburg

Sumayya Vally: At the Bawa House last week. Pic by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Sri Lanka and was honoured and indeed delighted to receive the invitation. But it was to an eerily unquiet capital city of deserted streets that she arrived.

Days of violence, political turmoil and continuing curfews meant Sumayya Vally had to have her much-anticipated lecture live-streamed from the serene confines of the guest suite in the Bawa Colombo house off Bagatelle Road, than delivered in the Hector Kobbekaduwa auditorium as planned.

Still the young South African has no regrets over the timing of her visit, reflecting that in her own homeland too, not too long ago such an uprising was taking place when she was starting her own practice in 2015. She is referring, of course, to the Rhodes Must Fall movement spearheaded by the youth against institutionalised racism and to decolonise education. “There is also something resonant and dear to my heart about that time and what we see happening now,” Sumayya says and some of that spirit, she hopes, is in her practice – a call for change through imagining the world differently and saying things can be done another way. That movement led to significant change. “I feel very hopeful of what young people in Sri Lanka are saying to the world – it’s been incredibly inspiring to see.”

For one whose practice has striven to give space to diverse and disregarded voices, the work of artists at Gotagogama through installations, projections and ritualistic performance resonates. She talks of the importance of artistic expression in times of crisis and the need to show solidarity with each other.

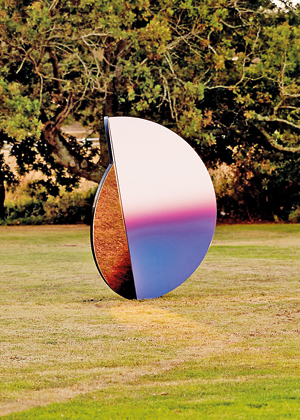

Colour and light: Folded Skies installation

There was some brief respite from the deepening crisis also, to slip away to Lunuganga, to see Bawa’s country estate perhaps the way it was meant to be experienced, she says – in solitude, to gain some insights into the work of the master architect.

Sumayya’s architectural practice is based in Johannesburg but her growing stature as an architect has seen her build an enviable reputation internationally. Named one of Time’s 100Next – young leaders for the future in 2021, she was also commissioned to build the Serpentine Pavilion 2020, an honour that has earlier gone to famous names like Frank Gehry, Oscar Niemeyer and Zaha Hadid. Notably she was the only architect on the Time magazine list and the youngest ever invited to design the Serpentine’s annual temporary summer pavilion on the grounds of London’s Kensington Gardens as a community space for the arts.

Sumayya started her design studio Counterspace while graduating in 2015, a collaborative effort with other like-minded friends without too many expectations, her intention being a more research oriented practice where she would have the space to explore her love for Johannesburg, rather than being confined to a more traditional architect’s office where creativity could perhaps be stifled. “The way I approached it was just to start and go about it without any pressure, but with a lot of vision for the kind of work, the kind of interests I wanted to pursue,” she says adding that she can still see all the same interests and intuitions as before, though of course, now, the opportunity to translate them is bigger.

“I think architecture is a profession you can pour any interest into because it’s so much about the human condition, and it touches so much of our lives. I feel very lucky to be able to have furthered those interests through architecture – history, archaeology, language and how we express the stories of people. I think my ultimate love is how we express those stories through design…..”

A meeting place: The Serpentine Pavilion designed by Sumayya

Counterspace has been exploratory and inter-disciplinary in both concept and design, from sound, film, installations and food community projects, all rooted in an interest to express something of a place. Most of her work has been in Johannesburg – a city she is endlessly fascinated by. “So many complex phenomena that make the city what it is; its atmospheric conditions, its ritual lives, its urban morphologies, its rhythms in the way people set up trade.” Sifting through Johannesburg’s toxic mine dumps, which under the apartheid regime were used a means to segregate the city, Sumayya also uncovered many layers of forgotten stories and buried histories, using the fragments in a display of 90 petri dishes for the Chicago Architecture Biennial 2015/16. The mines project also gave rise to ‘Folded Skies’ – an installation of circular metal frames at the Stellenbosch wineyard where she recycled the pigments and run- off from the mines to mirror the skies above Johannesburg coloured by the mine dust. Another project – the Pan African Plates examines how the South Asian and Muslim migrant communities come together over food and rituals, both projects looking to express something that is very African in its DNA, she says.

Sumayya herself grew up in the Indian only township of Laudium and says she had a ‘small community’ upbringing, attending a Muslim school. Of Indian origin, it was in 1947 that her grandfather migrated to South Africa. “I feel very blessed to have had that strong community upbringing,” she says, and that has definitely informed her work. There was that sense of the collective working together – lots of mobilizing, organising, charity initiatives, as a student walking to the embassy to take part in protests – all that came from being part of a community that identified with a broader global community because it is diasporic, both the condition of being diasporic Muslim, diasporic Indian, African, South African– all those layers representing different forms of struggle that also engender solidarity.

When the very prestigious Serpentine Pavilion commission came her way, her practice manifesto had thus far been about expressing Johannesburg and she looked to translate that into expressing London to London. She started her research with a very thick timeline of the history of London – the heart of industrial colonial empire and the movements, the waves of migration that occurred due to that. “I wanted to tell something of those histories,” she says, exploring strands of these migrant communities, some of them no longer in existence. The Pavilion – a circular structure of muted elegance made of sustainable materials – reclaimed steel, cork and timber took shape with four Fragments intriguingly placed around London. “It was inclusive but also generative, she says, with people from different walks of life coming to the pavilion but also the Serpentine, as an arts institution interfacing with diverse communities. Even though now ended, her work in the city continues in many ways, this August at the Tabernacle community centre, a continuation of Fragments – a procession of pieces will honour the elders who were at the genesis of the Notting Hill Carnival.

More exciting ventures are on the horizon – the Islamic Arts Biennale in Jeddah in December 2023 where she will be a curator opens doors to commissioning art and shaping perceptions of what Islamic art can be in a manner that is not Western-centric. “I really want this to be a biennale about embodied experiences and the cultural life of Muslims – the first set to be very much expressions of spirituality and rituals that everybody who has a relationship with faith can relate to and even those who don’t can find meaning in, how rituals are arranged around constructions of time and how we are brought together from all over the world by practising these rituals. The second set of experiences is cultural – infrastructures of galleries and forms of community and intelligences that are embedded in the faith.” The Presidential Library in Liberia will see her design the exhibition spaces, again a chance to work with the methodologies of story telling from West Africa and the continent that are more immersive and aural.

Amidst this busy world of research and practice, she makes time to teach back home– it has been right along intertwined with her studio practice and she says working with young people (not much younger then herself – she is just 32) has been truly inspirational, providing them a strong space for longer research but also seeing traditional perceptions of architecture being questioned.

For an architect who dares to dream, to whom it matters deeply to be able to work from a place of aspiration rather than from a place of issue (even though the two are intertwined), she ended her Bawa memorial lecture, by reading out her letter to a young architect published in the Architectural Review in 2020 which says so much of her own philosophy:

There is always architecture waiting to happen in places that are overlooked

You will fall in love with gold, kitsch, supernatural ideas

With very strange and everyday things – a disco church on wheels in the inner city

The performance of a ritual gathering on a patch of veld grass of a traffic island next to the highway

The rhythms and space of an Ethiopian coffee ceremony

The smell before a Highveld thunderstorm

The choreography of Fordsburg on a Friday, before prayer time

The specific colour spectrum of a mine-dump sunset

The tenacity of indigenous plants and indigenous ceremonies– all the magic that is Joburg.

There is another canon here.

Ingest atmospheres– learn how to read and feel colour, dust, mist, the phases of the moon. There is another canon here

Look at these things deeply

Feel them, absorb them

You will soon develop a mistrust for the historical record. Listen to that.

Look so deeply at what is present that you notice the silences and the absences too. There is yet another canon here, in these silences and absences.

Read in other languges.

Write in your mother tongues. Look deeply at sentence structure and vocabulary. There is another canon here.

Learn how to dissect the index of an archive.

And how to make your own indexes for archives.

Stay soft and sensitive – it is a deep strength, and architecture needs it. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

Don’t listen to anyone who tells you that everything you can ever imagine has already been done. They are incorrect.

Beauty and social justice are not mutually inclusive. Beauty is social justice.

There is an infinite number of untold stories, unheard voices, unrealised dreams, undreamt worlds.

Poetry is a necessity.

And dreaming is everything.

(Sumayya Vally’s lecture is up on the Geoffrey Bawa Trust

YouTube channel – https://youtu.be/XiVk1JCqKGU)

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.