News

Sri Lankan fishermen world’s biggest manta killers feeding Chinese demand

View(s):By Malaka Rodrigo

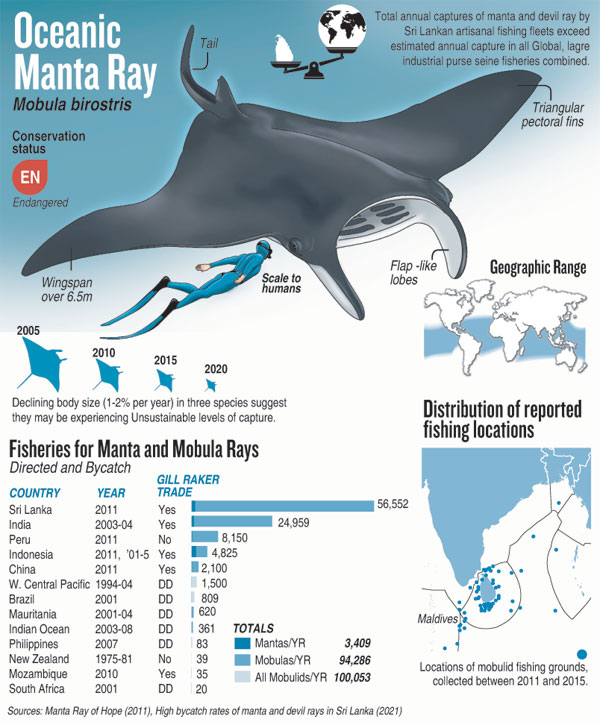

Sri Lanka holds the dubious record of killing the most mantas and devil rays compared with all global and large industrial purse seine fisheries combined.

A survey of local fish markets from 2005 to 2020 also has revealed that this level of manta fishing is not sustainable.

According to the Manta Trust, manta and devil rays, known collectively as mobulids, are some of the most beautiful, fascinating, and enigmatic creatures in the tropical oceans. These fish are close relatives of sharks and have a diet of plankton that they filter feed while on the move.

Like the sharks, these mobulid rays have a very low reproductive rate, where some become sexually mature in about 10 years and then the female gives birth to a single pup after a gestation period of about a year.

A giant manta ray swims like a flying saucer. Pix by Simon Hilbourne/ Manta Trust

“Hundreds of mobulid rays are caught on a daily basis in our waters, so one does not need to be a genius to conclude they would soon be overfished,” says Daniel Fernando, a marine biologist of the Blue Resources Trust.

Mr. Fernando and the team surveyed fish landing sites over nine years between 2011 and 2020, covering 38 landing sites in Sri Lanka. They collected data on catch numbers, body sizes, sex, and maturity status for five mobulid species. The data revealed that giant devil ray (mobula mobular) is being fished at rates far above the species’ population growth rate, and the average sizes of all mobulids in the fishery except for giant oceanic mantas are declining.

As per a report on the Global Threat to Manta and Mubula rays, out of the 3,409 manta rays captured by 13 countries a year during the study, Sri Lanka’s fishing fleet caught 1,055; or one-third. But, when considering all the mobula rays, the total global catch recorded a year was 100,053; while the Sri Lankan fishing fleet was responsible for 56,552; accounting for nearly 60% of the global catch.

International demand over the last decade for mobulid gill plates — the cartilaginous structures that filter plankton from the water column — for traditional Chinese medicine has directly led to an increase in fishing and retention of these species in bycatch fisheries. In Sri Lanka, they often get entangled in gill nets.

“Earlier, we were not interested in these rays and sometimes throw them away, as ray flesh is low value. And we prefer to keep space in our boats for the more profitable tuna,” said Mr Roy Thomas, a fisherman in Negombo who works in a multi-day boat. “But, now, these rays earn more money due to the demand for gill plates, so we bring them in.’’ There are some regular buyers and they remove the gill plates to clean and process for export, he said.

Mr. Fernando is also an associate director of Manta Trust, a global organisation dedicated to the conservation of mantas and other mobulid. The trust has a flagship project in Maldives, where the scientists have made the manta population the most studied in the world. The Maldives has several sites where the reef manta ray (mobula alfredi) visits seasonally depending on plankton availability.

In Maldives, speeding by tourists who come to watch mantas is estimated at US$8.1 million a year in direct revenue, based on a study in 2010. This amounts to spending of US$500 to US$4,000 a week.

“When you kill and sell a manta, it would be a one-off transaction, but if such tourism can be built, then Sri Lanka, too, may have the potential to earn dollars,” says Mr. Fernando.

Mantas are butchered in Sri Lanka as they are not a protected species

But, so far there are no recorded sites of manta rays gathering in Sri Lankan waters. Local waters seem to be an important nursery ground. A large number of mantas caught in Sri Lankan waters are juveniles, the marine biologist said.

The species found in the Sri Lankan territorial waters is the giant oceanic manta ray (mobula birostris) which is now globally ‘endangered’, Mr. Fernando said.

It can grow up to 9 metres (30 feet) maximum and to a disc size of 7m (23 ft) across with a weight of about 3,000 kilos. But, those caught in Sri Lankan waters is less than half this size.

Simon Hilbourne, a British marine scientist of the Manta Trust, studies the giant oceanic manta rays in the Maldives and Sri Lanka. He says more research is needed.

“The home range of some populations have been found to be around 100 kilometres, which is not a long distance in terms of oceanic measures,”Mr. Hilbourne said.

Research by the trust also found a possible breeding aggregation of the giant oceanic mantas near the Maldivian island of Fuvahmulah.

“But, most of the time we record different individuals at the site and the only way to unravel the movements of these giants is satellite tagging,” Mr Hilbourne told the Sunday Times. He said the possibility of tagging these rays in Sri Lankan waters too was considered, but as it would be different to locate them, the idea was dropped.

In the Maldives, the reef mantas were tagged, so their regular visits are recorded. The photo ID using spot patterns, scars, and other special markings can be used to identify individuals, says Ms Joanna Harris who studies the mantas of Maldives.

Climate change could also pose a threat to the mantas as it would reduce and disrupt the drifting patterns of oceanic planktons and also destroy the coral reefs that reef mantas are using as cleaning stations, said Ms. Harris.

A large number of juveniles are landed in the fish markets and makes up the largest number of juveniles recorded anywhere in the world so far.

It is highly likely that there is a nursery ground around Sri Lanka. So it is of utmost importance to protect them. In Sri Lanka, none of these mobulid rays is protected, but international treaties such as the Convention on Migratory Species and the Convention of International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES), apply.

The giant manta ray is in the CITES list of Appendix II, so special permission is needed for export.

The Giant Manta Ray is in the CITES list of Appendix II, according to which the country needs to give special permission to export them.

Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Director General Susantha Kahawatta said the department issues permits for gill raker exports after consultation with CITES.

In Sri Lanka, among the five species of sharks that are illegal to be caught are thresher sharks, oceanic whitetip sharks, and whale sharks. Mr. Kahawatte said the law is being enforced by the Navy, the Coast guard, and the department’s fisheries inspectors. “They take action, whenever our scientific arm makes recommendations on severely depleting populations of mobula rays,” the DG told the Sunday Times.

The government’s marine research agency, the National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency (NARA) conducted small-scale research in 2018 on Manta Rays. Of the 46 specimens observed, 95% are juveniles or sub-adults, indicating the nursery grounds might be located close to Sri Lanka’s fishing grounds, said Dr. Chintha Perera, the leading scientist of the research. The research also recommends releasing into the sea live manta rays entangled in fishing gear.

NARA research also found few reef mantas too in fish markets. As there are no records of reef mantas in Sri Lankan waters, it is likely the Sri Lankan fishers caught them illegally in areas such as Chagos, a British Indian Ocean Territory near the Maldives, he said.

On September 27, the World Tourism Day was celebrated under the theme ‘Rethinking Tourism’. Perhaps it is time for Sri Lanka to think more about marine tourism and not empty the oceans of the charismatic species in our waters like the mobulid rays that have more potential to earn dollars, Mr Fernando told the Sunday Times.

This story was produced with

support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network

The best way to say that you found the home of your dreams is by finding it on Hitad.lk. We have listings for apartments for sale or rent in Sri Lanka, no matter what locale you're looking for! Whether you live in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Matara, Jaffna and more - we've got them all!