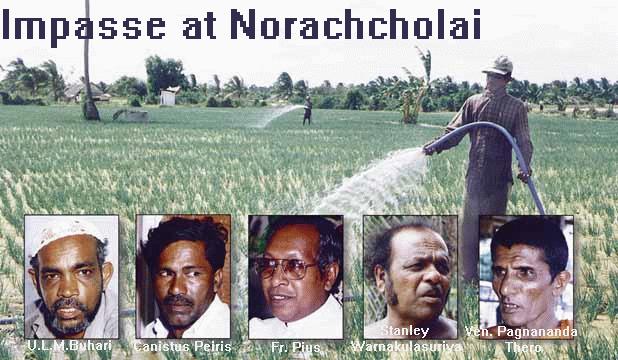

Every morning, even before sunrise, the people of Norachcholai are awoken by loud constant buzzing. It is the sound of a hundred, no, a thousand motors pumping water from the ground to feed their cultivations. From dawn to dusk, the fields are watered to prevent the blazing sun from having its way with the thriving plantations.

Blessed with abundant fresh water, the land produces many a crop, from onion to bathala to cabbage and beetroot. Coconut trees the size of a man bear fruit- so fertile is the land. The seas yield a good harvest of fish and the lagoon, crab and prawn.

But the people of Norachcholai are not happy. In fact, they live with a constant cloud over their heads. For Norachcholai is the chosen site, the location decided upon by the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) for the much talked about coal power plant. Not knowing what will become of their homes and fields the residents are in a rebellious mood. Especially since at a protest rally in the town on April 25, a man was killed when police opened gun fire to disperse the crowds.

The Ceylon Electricity Board now is in a quandary, attempting to find a solution for the crisis that has arisen at their chosen site. The feasibility studies that the CEB was carrying on at Norachcholai have come to a standstill because of the inability of the CEB staff to work at site. Some equipment was set on fire earlier and workmen who tried to work with police and armed guard protection has given that up too by last week.

"The government will have to take a decision whether to go ahead with coal or not very soon," a frustrated CEB ‘high-up’ told The Sunday Times. "At this rate we will never meet the deadlines for power generation and there will be blackouts again."

The people of Norachcholai are equally frustrated. "We have never been informed by the CEB as to what exactly is going to happen here," villagers complain. "When they first came to study the site the CEB did it under various pretexts, using excuses like road development and building stone embankments on the coast. Therefore we can never believe what they say." They are also very determined. "They can kill us here in our village and build the power plant over us, but we will not move elsewhere," they say. This sentiment was echoed throughout the village in one voice, regardless of the language in this very mixed community.

Norachcholai lies in the Puttalam peninsula between Mampuri and the famed Talawila church. It is virtually an oasis in an otherwise arid landscape. Clean ground water being available throughout the area, despite being in between the sea and the lagoon, has facilitated large scale cultivation. The land was colonized some 30-40 years ago when it was just sandy desert dotted with palmyrah, but now there is not a patch of uncultivated land to be found. Most farmers being in the second generation of settlers, have small fields of one or two acres. The richer of them own 20-30 acres. Companies have bought large plots to cultivate. But all earn a comfortable living. All have their own homes- some are so grand as be considered palatial in city terms. What’s more, the peninsula has absorbed a large portion of the refugee flow from Mannar. Unofficial estimates say that there is a refugee population of 30000 at present. These people too work as daily paid labourers in the fields. The peninsula provides a good portion of the country’s requirement of coconut, dry fish, prawn, shrimp, fish and vegetables. The evening pola at Norachcholai attracts some 50 lorries daily, transporting vegetables to various parts of the country. What the people most fear is that they will be made to leave the village if the project goes ahead

"It is not an arid area as is so claimed by the CEB," Fr. Pius, Parish Priest of Talawila said.

"These people have worked hard to make it a thriving, fertile farm land. Their fears are justified. Even if they are relocated, they will have to begin from scratch once more."

The Electricity Board has found, much to their consternation that they are not merely up against a group of farmers and fishermen in a remote township, but many Non Governmental Organizations and religious groups as well. The villagers themselves are organized into a protest group. SEDEC (Socio- Economic Development Centre) a Catholic organisation became involved in the protest when the villagers appealed to their Chilaw office for help.

"We conducted several awareness raising programmes in the village," a SEDEC official said. "aiming to educate them on coal power and its possible environmental repercussions."

"This area is very windy," Canistus Pieris, a fisherman turned farmer said. "Even if we don’t have to relocate, our fields would be destroyed by the black dust carried by the wind. Also when the jetty is built, the coast will begin to erode on the northern side. This will affect the Talawila church," said this devout Catholic.

The people also protest at the treatment they have received at the hands of the police. Police had come and searched a number of houses looking for weapons. Then they had strict police protection at a CEB- villagers meeting at Puttalam. "We are not criminals. We are innocent people fighting for our rights," Stanley Warnakulasuriya, a fisherman living by the coast at Norachcholai said.

Even though environmental concerns over the project have greatly influenced decisions of its location earlier, here, the people are primarily worried of possible relocation. The CEB has given assurances that it will take utmost precautions to keep the pollution levels at minimum. They have gone to press declaring that they will use modern effluent control systems and filters to reduce the carbon particles in the smoke. But unfortunately for the CEB, people of this area constantly see the ravages done by the Puttalam Cement Factory on the surrounding environs and are not quite ready to believe that the CEB will actually take such precautions.

"It is difficult to believe that they will really bring the best quality coal and put in very expensive filters to control pollution. Our experience with the state proves otherwise," a villager K.A.D. Appuhamy said.

Another factor that holds strong in Norachcholai is the unity among the different communities living there. A mostly Sinhala Catholic area, Norachcholai has a sizeable Muslim population and smaller Buddhist and Tamil/ Hindu groups. They all speak together. The associations are represented in all communities. Ven. Pagnananda Thero holds meetings at his temple for a Muslim audience. Everyone speaks Sinhala and Tamil. And in one voice they refuse to move from Norachcholai. "I would rather die than leave this area. What will we do in a completely new land?" U.L. M. Buhari said. Several youth had shaved their heads in protest of the police treatment and the killing of a villager, M. Somasiri.

The CEB therefore is presented with quite a problem. More than a decade after the idea of a coal power plant was introduced, they had at last been able to identify a site that appeared ideal, after rejecting a number of sites in the Eastern and Southern coasts. The sea off Norachcholai had the depth needed to build a port into which the ships carrying coal would come. Now they have met with an unforeseen adversary. What frustrates the Board most is that while the project is already behind schedule there is still a long way to go to begin construction.

"We were trying to do the feasibility studies at the site," D.C. Wijeratne, Additional General Manager, Planning, CEB said. "If after the feasibility studies, the site proves suitable then we have to negotiate with the Japanese government for finances. But we have not been able to progress much at all."

The Electricity Board criticized severely for the power shortages that have cost the government and the consumer dearly, defend their position. "How can we go ahead with projects when there is no co- operation from the public?" an official demanded. The coal power plant, an initial 300 MW, was expected to be commissioned by the year 2002. "Now it will take at least an year or two more. The more we delay, the danger of another and very serious power crisis looms closer," D.C. Wijeratne said.

Coal is our best option, the CEB claims. Now, the government has to take a decision about Norachcholai. Will it be the people or will it be coal power?

Continue to Plus page 2 - Teaching the child in a way he can learn * ‘Pansale Piyatuma’ at the age of 95

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to

info@suntimes.is.lk or to

webmaster@infolabs.is.lk