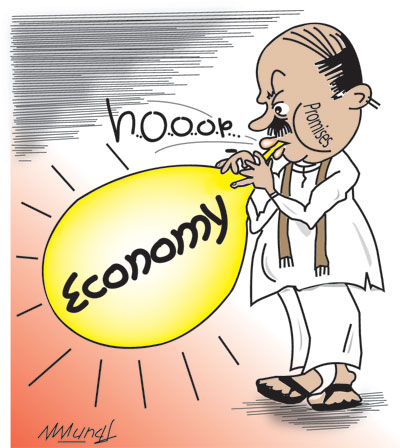

The economics of opposition: Promises kept, unkept and cannot be fulfilled

In fact what is witnessed, especially at election time, though not limited to it, is the economics of the impossible. The economic constraints of poor countries are ignored by electoral politics in many developing countries. Nowhere is this phenomenon more conspicuous than in Sri Lanka, that has a history of 66 years of electoral politics based on universal franchise. Instead of a maturing of the political process to understand the facts of economics, the years have only accentuated the promising of the impossible. The political scene today is no exception. The opposition is screaming saying it can solve every economic problem that it failed to resolve when it was in power. There is a lack of recognition of the accumulated fiscal liabilities and the uncontrollable international market forces. Consequently the focus of criticism of economic policy is warped and misdirected. Promises are both political and economic. And political promises have economic consequences. Perhaps the most daring and consequential political promise was the 1956 election promise of “Sinhala Only in 24 Hours”. The repercussions of implementing this promise have had horrendous impact on the economy. There have been a multitude of economic promises from the promise of consumption and production subsidies, welfare payments, subsidised ration to providing employment. Most of these promises are not kept fully. Some are kept fully or partially and tend to be disastrous to the economy and polity. The most notorious and far reaching election promises in the past have been on the food or rice ration. The history of the rice ration is the most interesting one where parties vied to give a better deal and ultimately the auction of promises led to a free measure of rice, an unparallelled policy in any country. The promise of Rs. 2,500 a month under the Janasaviya is another excellent example. These promises have the character of promising the impossible and the implementation of the promise in part. The costs of such promises are enormous and implications of such public expenditure are economically unbearable. When such promises are made there isn’t the slightest consideration of how the funds could be found or what economic repercussions would follow were the promises implemented. In most cases some part of the promise is fulfilled in one way or the other. Even the partial fulfilment of such extravagant promises is harmful to the economy. What is worse, the benefits do not reach the intended beneficiaries, as was the case in food stamps, Janasaviya and Samurdhi. A fundamental reason why people believe in election promises is that they think that the government has an unlimited capacity to give. There is a lack of understanding about how the government finds the resources to confer benefits like subsidising consumer items or production inputs. The idea that the government has inexhaustible resources of finance to confer these benefits or that the resources are found from others—the rich sectors of society-- is central to the clamour for government interventions to give handouts. The economic implications and repercussions are not therefore a concern among the bulk of the electorate. This perspective is strengthened and maintained by the very low proportion of the population that pay personal income taxes. Indirect taxation burdens or the inflationary impact of the consequence of government spending are not understood. A pathetic spectacle is that of opposition parties promising to give things they were unable to when they were in power. Incumbent governments are haunted during their tenure by the promises they gave but could not keep. On the other hand, they face the financial burdens and consequences of the promises they kept. Right now we are witnessing some of these features even though there is no certainty as to when the next elections would be. The current high rate of inflation has both unavoidable and avoidable factors. The rise in international prices, especially of oil, is at the core of this issue. It is one that cannot be controlled. It must also be understood that there is a secular long term trend of declining resources of oil reserves and that international prices are likely to escalate further. As a non-oil producing country we have to face this international trend. To subsidise oil prices to benefit consumers is a measure in the wrong direction. The burden would ultimately fall on the poor and fiscal policy would be distorted. If petroleum products are subsidised people would require paying indirectly through higher inflation or other taxes. Yet, the opposition is vociferously against fuel and electricity price increases. Promises of the opposition to bring down prices of imported goods like milk powder, gas, petrol, sugar and other basic items that are imported in large measure are empty promises. In fact if such prices are brought down through subsidies the remedy could worsen the economic situation. Much of the inability of governments to bring down the fiscal deficit is owing to the partial fulfilment of election promises. A case in point is the employment of graduates into a public service that is already overstaffed with poor quality persons. The inability to make the Samurdhi programme a better targeted one to the really poor is another example. Opposition parties that promise the impossible could be in a Catch 22 situation. If they fulfill these promises there could be dire repercussions on the economy, if they don’t then they face the wrath of the people to whom they have pandered in opposition days. In mature democracies, whenever parties promise a benefit, whether it be health care or a subsidy, the question the electorate asks is how will the government find the funds? In fact at election time parties have to explain the financial implications of their policies. People know fully well that “there is no such thing as a free lunch.” Regrettably such a political culture, political maturity and understanding of fundamental economic principles are sadly lacking in our electorate. Political parties keep pandering to this ignorance. |

|| Front

Page | News | Editorial | Columns | Sports | Plus | Financial

Times | International | Mirror | TV

Times | Funday

Times || |

| |

Reproduction of articles permitted when used without any alterations to contents and the source. |

© Copyright

2007 | Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. All Rights Reserved. |

A characteristic of democratic politics in developing countries is that opposition parties make extravagant promises that can or never should be fulfilled. Electoral politics hardly recognises the fundamental basis of economics that resources are scarce. Politics, on the other hand, is said to be the art of the possible.

A characteristic of democratic politics in developing countries is that opposition parties make extravagant promises that can or never should be fulfilled. Electoral politics hardly recognises the fundamental basis of economics that resources are scarce. Politics, on the other hand, is said to be the art of the possible.