Art of brevityPublishers embrace short nonfiction, from presidents to science NEW YORK (AP) - As he prepared a biography of Edgar Allan Poe, author Peter Ackroyd read through more than 20 volumes of Poe's work and filled two file cabinet drawers with notes - more information than the most devoted fan could absorb in a lifetime. It was all for a book that will run less than 200 pages, that can be read within a few hours."It's like writing an essay, rather than a biography," says Ackroyd, who has written an 800-page book about London and 500 pages about Shakespeare. "It's an exercise, in style as much as in substance. It's an opportunity to capture the broad strokes of a life, a career, a world, in ways which are probably impossible in a large-scale biography."

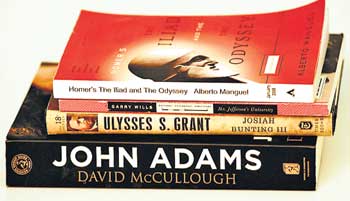

It is a showcase for the art of brevity. In the decade since James Atlas revived the form with his "Penguin Lives" series, at least 10 publishers have started their own lines of short, nonfiction books, on subjects ranging from scientists to presidents to mythology. Although the advances are low - and sales often to match - short books have attracted such best sellers and prize winners as novelists Jane Smiley and Larry McMurtry, essayists Christopher Hitchens and Bill Bryson, and historians Robert Dallek and Sean Wilentz. "I like this trend. It's fine, old-fashioned self-improving middlebrow literature," says humorist P.J. O'Rourke, who wrote a brief work on Adam Smith's "The Wealth of Nations" for Grove/Atlantic's "The Books That Changed the World" series. The nonfiction sketch dates back at least to Plutarch and has been upheld over time by John Aubrey in the 17th century and Lytton Strachey in the early 20th century. But never, Atlas and others says, have so many publishers been in on the trend at the same time, even if opinions differ on why there is a trend. "I imagine a highly educated, reading public, readers of The New York Review of Books, readers of The New Yorker, readers of The New York Times Book Review," says Atlas, who currently edits the Eminent Lives series at HarperCollins. "There is an audience I know empirically exists out there of several hundred thousand readers who have a dedication to the idea of being educated, in the highest sense." "It's not a gigantic commitment to read one of those books," says Grove/Atlantic publisher Morgan Entrekin. "It's not like picking up 'The Looming Tower' or 'The Coldest Winter.' You can educate yourself about something in a short of period of time." Ackroyd has his own personal line with Doubleday: "Ackroyd's Lives," a planned 10-book series for which works on Chaucer, Sir Isaac Newton and J.M.W. Turner already have been written. The Canongate Myth Series, short books on mythology, expects contributions from Margaret Atwood, Joyce Carol Oates, Donna Tartt and several others. Graywolf Press has started "The Art of" series, edited by award-winning fiction writer Charles Baxter, who contributed a work on "The Art of Subtext." At Palgrave/MacMillan, former NATO commander Gen. Wesley Clark is overseeing a series of short military biographies, including books on Stonewall Jackson, Omar Bradley and Douglas MacArthur. "They're written in a very direct style, for the general public, to make these stories more accessible," Clark says. "They're the kinds of books you can pick up at an airport and finish in 4-5 hours and if readers are really interested, they'll seek out longer, more scholarly books." If the ideal reader is an educated self-improver, the ideal writer is versatile, prolific and provocative, such as Garry Wills, who has written short books on James Madison (for the Times Books series on American presidents), Saint Augustine (for Penguin Lives) and Thomas Jefferson's home at Monticello (for National Geographic's "Directions" series). Other favorite short-form authors include Francine Prose, who has written short works on Caravaggio (for HarperCollins' Eminent Lives) and gluttony (for an Oxford University Press series on the seven deadly sins); Paul Johnson, books on Napoleon and the Renaissance; and Karen Armstrong, works on Buddhism and Islam. With advances of $100,000 (euro66,000) at best, the art isn't only in writing the book, but in finding the writer. Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. urged Bill Clinton to write a short biography of Abraham Lincoln for Times Books, but could only promise prestige, not the former president's multimillion-dollar market price. Atlas recalls asking for Henry Kissinger on another project, only to be told his starting price was $2 million (euro1.3 million), "several zeros over my limit." But sometimes a little pleading works. For Eminent Lives, Atlas tried to lure essayist, travel writer and linguist Bill Bryson to write a short book on Shakespeare. Bryson, author of such best sellers as "A Walk in the Woods" and "The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid," ended up writing one that came out last year. "We try to elicit enthusiasms," Atlas explains. "I sent out these missives to writers I admire, sometimes into the Internet ether and sometimes by actual post. I sent some letters to Bill Bryson and sort of forgot about it until a few months later I got this letter from him. There's one word, followed by a question mark: 'Shakespeare?"' |

|

||||||

|| Front

Page | News | Editorial | Columns | Sports | Plus | Financial

Times | International | Mirror | TV

Times | Funday

Times || |

| |

Reproduction of articles permitted when used without any alterations to contents and a link to the source page.

|

© Copyright

2008 | Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. All Rights Reserved. |