Three decades after migration, ‘housemaids’ still a crisis pointBlame game won’t solve problems

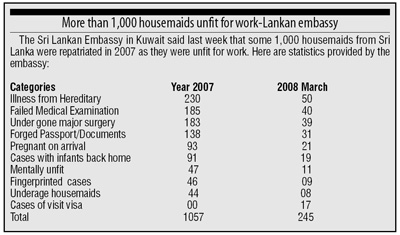

Some three decades after Sri Lankans began migrating to the Middle East for employment, the country is still coming to grips with a major issue – the plight of Sri Lankan housemaids in the country of work and the social breakdown in their families.While the job agent has been the favourite ‘punching’ bag for the problems faced by some 600,000 to 700,000 Sri Lankan housemaids overseas, most of us have on the other hand failed to take into account a key factor in the crisis: “Does the worker seek a job on their own accord or is coerced into employment?” During a visit to Kuwait two weeks ago to witness the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding between associations representing job agents in Sri Lanka and Kuwait, agents there and from Colombo complained of an ‘unfair’ media not looking at the ‘whole’ picture and instead relying only on the version of the housemaid. Agents, they said, were slandered and ridiculed when a housemaid had a problem. “One of the biggest problems is that the worker is ill-prepared, doesn’t have a clue about household equipment or is coerced by fellow workers to jump ship (leave the home of the employer) and seek free-lance work outside. It is a selection problem and also ill-preparedness on the part of the housemaid,” noted Zain Milhan, President of the Sri Lanka Manpower Welfare Association (SLMWA) in Kuwait, pleading for a balanced approach by the media to the issue. “There are many sides to this crisis. Job agents are also at fault because selections are not good. On the other hand the housemaid must also take the blame for being ill-prepared or deciding to work overseas despite long hours, unfamiliar equipment, in an alien culture and unable to understand the language.” Fiction: Housemaids are well briefed Fact: They are clueless about what to expect at that end Fiction: They are well trained prior to arrival Fact: Washing machines at the training centre are 10-20 years outdated and semi automatic, according to one agent. Latest models are being used overseas and often break down due to ignorance or inability by workers to read instructions. They are penalised via cuts in wages for machine breakdown Fiction: Sri Lankan housemaids should get a salary comparable with their Filipino counterparts because they possess the same skills Fact: Filipino housemaids are better equipped to handle modern household equipment; they speak English, dress well and are sophisticated. Because of this, they can command a higher wage However one established fact in Kuwait, confirmed by a senior official at a Kuwaiti Ministry handling employment of foreigners, is that many Kuwaiti homes prefer Sri Lankan housemaids because they are easy to work with -- once they have established themselves – and are friendly and hard working. In this context, some Kuwaitis are willing to pay a premium for a good housemaid from Sri Lanka even though they possess lesser skills than Filipino workers. In Kuwait, the SLMWA and the Association for Licensed Foreign Employment Agents of Sri Lanka (ALFEA) came together and agreed – in a commendable move – that they are much at fault as anyone else in problems faced by housemaids. “If not for the housemaids or other professions, we won’t have an industry. We’ll be without jobs or a business ourselves,” said ALFEA President Suraj Dandeniya. Some 200 agents from both associations who gathered in Kuwait for the historic meeting, through the MoU, acknowledged the problems and pledged to work towards the welfare and protection of housemaids in the second largest employing country in the Middle East, for Sri Lankans. Most of us in the media rely on second-hand reports from returning housemaids or officials about the crisis facing our workers because of the inability to see for ourselves the ‘real’ situation in those countries. Often we are told about the harassment, rape, abuse, non payment of wages, etc. Rarely we are told that a situation has been created because a worker was homesick and wanted to return home, yearned for an infant that had been left behind or was too sick to work. However during a research project that I undertook in 2004 and 2006 for an NGO looking after the welfare of workers, housemaids themselves told me how women virtually abandoned their Sri Lankan families, lived with other partners (Indians, Bangladeshis or Pakistanis) and had children from these new alliances. In Jordan, I was told by two nuns working for Caritas there who visited homes of employers how new workers were coerced by other ‘veteran’ Sri Lankans to leave their first employer and work outside as free-lancers, leaving their passport and other travel documents with the first employer. They then join the ranks of illegal workers and fall into trouble. The nuns pleaded with me, “Please bring a law in Sri Lanka where women with young infants are not allowed to go abroad.” They said many women with young children were homesick, depressed and regretted leaving their children behind. While I was unable to speak to Sri Lankan housemaids during my recent Kuwait visit which was sponsored by the two associations, former housemaids who carry the designation of ‘Secretary” but actually run job agencies in Kuwait – there are many of them – spoke of the numerous cases where workers leave their first employer before contracts are over and team up with other men including Sri Lankans. “We have always warned them against leaving their first employer because they become illegal workers. But they don’t listen,” one agent said. One think is clear: The job agent is not entirely to blame for the crisis facing housemaids. Of course the agents are at fault for wage issues when the contracted wage is not paid or for sending a housemaid to an employer who has been accused of harassment and other abuse in the past. On the flipside, housemaids must take responsibility as they are not forced into employment and decide to go overseas as an independent choice.

The solution lies in a broader view of the issues facing migrant workers, bringing together all stakeholders – the government, workers, agents, welfare associations and families of workers – and preparing a roadmap for the next 30-50 years on how we need to move forward in this sector and most importantly, make sure housemaids are better skilled and modeled into an honourable and noble profession like any other skill rather than as a means of foreign exchange for the country and an avenue to relieve our employment problems, as it is now. Housewives and stay-at-home mothers perform an important role in society, a role that should be measured in economic terms and what it would cost the household budget if this role is to be outsourced. Similarly, housemaids and domestics, even in Sri Lankan homes here, perform an important role in the economy of a country and must be seen as an integral part of a country’s workforce. (The writer is Consultant Editor-Business at The Sunday Times and has spent years writing and researching on issues confronting Sri Lankan migrant workers. He believes there should be a rational and pragmatic approach to the problems rather than the blame-game syndrome which is never going to resolve the problems of the workers. The fact that job agents are acknowledging weaknesses in the system, he says, is a step forward in turning Sri Lankan housemaids into a profession that commands respect from society. The biggest challenge however is in bringing together agents and civil society groups looking after the interests of workers and working towards a common goal, a common vision.)

|

|

||||||

|

||||||

| || Front

Page | News

| Editorial

| Columns

| Sports

| Plus

| Financial

Times | International

| Mirror

| TV

Times | Funday Times || |

| |

Reproduction of articles permitted when used without any alterations to contents and a link to the source page.

|

© Copyright

2008 | Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. All Rights Reserved. |

Furthermore the lack of information about the country, its people, language, work conditions and type of work plus the fact that this category of Sri Lankans have never stepped out of their village to see the ‘rest of the world’ or the ‘rest of Sri Lanka’ for that matter makes them ill-equipped, ill-prepared and unskilled to aspire to be a foreign housemaid – whatever the economic (desperate to earn for the family) provocation might be. Rarely does a well-prepared and semi-skilled housemaid face any difficulty in the workplace. There are thousands of housemaids who have done well overseas and worked for period of 10-20 years on renewed or new contracts. If they have a problem they won’t be going back and back many times over, as clearly seen in many parts of the Middle East.

Furthermore the lack of information about the country, its people, language, work conditions and type of work plus the fact that this category of Sri Lankans have never stepped out of their village to see the ‘rest of the world’ or the ‘rest of Sri Lanka’ for that matter makes them ill-equipped, ill-prepared and unskilled to aspire to be a foreign housemaid – whatever the economic (desperate to earn for the family) provocation might be. Rarely does a well-prepared and semi-skilled housemaid face any difficulty in the workplace. There are thousands of housemaids who have done well overseas and worked for period of 10-20 years on renewed or new contracts. If they have a problem they won’t be going back and back many times over, as clearly seen in many parts of the Middle East.