News

Grama Niladhari: Grassroots go-between State and common man

Thousands of grama niladharis across Sri Lanka join to form the pivotal link between the country’s governance and the public. Grama Niladhari, literally “village officer,” is a profession that has been around since the time of the kings, when they used to be known as village headmen. Over the years, they have earned more respect—and with that, more responsibility.

The pitiful state of a Grama Niladhari office on Cotta Road. Pic by Nilan Maligaspe

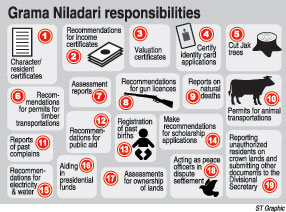

Today, each grama niladhari is responsible for a division that consists of about 1,600 houses. They meet with over a 100 residents each day, where they provide services such as issuing character certificates, reporting deaths due to natural causes, certifying identity card applications and acting as peace officers, among dozens of other tasks. Grama Niladharis are also responsible for maintaining records and visiting each house under their purview to distribute election documents.

“All governance decisions, even those made at the highest levels, come trickling down to us. We are the link between the policies and the people,” Nimal* a grama niladhari in Colombo said. Despite their remarkable importance in the functioning of society, these officers often work in crumbling offices built for them by the government. However, a majority of the grama niladharis in the country do not have government provided offices. They are, instead, given Rs 1,000 per month as rent to maintain an office.

“That is simply not enough to maintain an office. So, most of us end up renting a small room and cleaning it ourselves, or live in temples,” said Jagath*, a grama niladari who lives in a section of a house that he will have to vacate in six months.

“The house is in shambles. I cannot remain here much longer,” a worried Jagath said.

Lack of a proper workplace is just one of the problems that grama niladharis face. According to the Public Administration and Home Affairs Ministry, currently, there are 14,022 grama niladhari divisions, but only about 10,000 officers. “This means that, some grama niladharis end up running two or three divisions. We intend recruiting more people to fill the vacancies,” Ministry Secretary P.B. Abeykoon said.

While this recruiting takes place, officers are overworked and tired. Furthermore, they have to divide their time between each divisional office. “So, when residents come looking for us in one office, we are not there. Naturally, they feel frustrated,” Nimal explained.

While the minimum requirement to be a grama niladhari is the GCE Ordinary Level certificate, the All Ceylon Independent Grama Niladhari Association (ACIGNA) said there are about 1,000 grama niladharis in the country who are graduates, some with Master’s degrees.

Mohan*, a Grama Niladhari who has a master’s degree, said several such degree-holding officers had gone to Parliament to ask for a raise, but their efforts had proved futile. However, Mohan said that graduates should not be discouraged from the job.

“The more educated the grama niladhari, the more likely he/she would build constructive relationships with the division’s residents,” Mohan explained. Another problem that grama niladharis face is, not surprisingly, money. With a basic monthly salary of Rs. 15,000, Nimal said, most officers are forced to find some other form of employment as well.

“I, for example, have rented out a room in my house. That is how I am able to fend for my family,” he stated. Meanwhile, ACIGNA Chairman Chandra Jayasuriya said that the stipends these officers receive are barely sufficient. “We are expected to pay rent, electricity bills and clean our offices with Rs 1,000 a month. Furthermore, we use our own personal phones to make many work-related calls. The bills are paid out of our own pocket,” Mr. Jayasuriya pointed out.

A Grama Niladhari is given Rs 350 a month for house-to-house distribution of documentation. But the minimum distance of 15 km covered, is not the only thing that puts them off. “We have to fill tedious reports, in order to get that extra Rs 350. None of us bother with it. We have too much work as it is,” Mohan stated.

In an age of computers, cloud storage and ubiquitous internet, the job of a grama niladhari should not be as tedious as it was about a decade ago. For a long time, these officers have been promised laptops to store the records of thousands of Sri Lankans in their divisions—but Mr. Jayasuriya says this promise has not been fulfilled.

Ministry Secretary Abeykoon said Government intends to build a computer network between grama niladhari offices, divisional secretary offices and district secretary offices, and provide laptops to grama niladharis. He added that, in the past, select grama niladharis, with new ideas and projects from across the country, were sent to Malaysia for a special course.

“There are some officers who have created their own software and have records of their entire district. We selected 25 such motivated grama niladharis. It was the first time in Sri Lanka’s history that this sort of endeavour had taken place,” Mr. Abeykoon pointed out.

In the meantime, the people of Sri Lanka continue to go to their grama niladharis with problems of all kinds. You probably have your grama niladhari’s number written down somewhere. You probably don’t even know his name or haven’t met this person at all.

But he/she is working somewhere not far from you, the records of your existence locked in a cabinet in that very room. “We are doing service to the public. We are helping the common man, and that thought is what keeps us going. This is a great profession, perhaps second only to being a doctor,” Mohan reflected.

* Names changed to protect identity.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus