Little miracle

Saved from the rapidly-closing jaws of death!

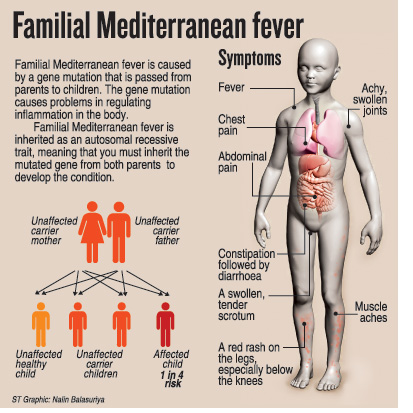

If not for the diagnosis of Familial Mediterranean Fever, a rare genetic disorder, reportedly for the first time in Sri Lanka on May 26, an 11-year-old would be dead.

Dr. Suriyarachchi Pix by Nilan Maligaspe

This is the miraculous tale of little Anusha* living on the very fringes of society and suffering from a rare disorder being diagnosed and treated.

It is also a reflection of how the free, state health system works for the benefit of the poorest of the poor, those without power, money or influence and those marginalised by society.

Pretty Anusha with her bright eyes who limps into the room of Consultant Paediatric Surgeon Dr. Chandima Suriyarachchi of the Lady Ridgeway Hospital (LRH) for Children in Colombo is painfully thin but all smiles.

Although the Sunday Times wishes to speak to her mother or guardian, to seek permission to take a photograph of Anusha who is alive because of a simple medical marvel, there is no adult by her side, only her 17-year-old sister.

The other side of the story spills out from the two girls living on the seamy side of a Colombo suburb. Their father is in the Welikada Prison and the two sisters, along with another younger sister who is about four, are living with their mother, grandmother and 23-year-old male cousin.

The grandmother is working in a home as a servant, we learn, while both children are quite cagey about the job that their mother is doing. Most probably, with her husband languishing in prison, she may be engaging, out of sheer necessity, in the oldest profession in the world to ward off hunger and starvation from her family. The eldest girl has not been to school in a long time, while Anusha is longing to get back to her books, as she hopes to become a teacher.

Prof. Seneviratne

Illness, mainly in the form of “perplexing” fever, had kept her away from the classroom and it is to a leading tertiary-care centre that she was taken first a while ago. The doctors there had diagnosed her condition on whatever available evidence, as that of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), an acquired multi-organ inflammation disease. Lupus is known as ‘wolf-bite’ due to the gaping wounds and ugly scars that come with it.

The Sunday Times learns that even while on treatment, fever rampaged through her body, with a burning sensation inside her tummy (abdomen) leaving her writhing with severe tummy pain.

The next admission was to a surgical unit of the LRH where on the diagnosis of appendicitis, an operation was performed on the girl with her mother taking her home, after getting her discharged against medical advice.

Usually, after such a minor operation, the patient should bounce back to health, it is understood. However, it was not so with Anusha. The fever recurred as did the severe pain and she was back at the LRH on May 15, this time admitted to Dr. Suriyarachchi’s ward, followed by a second operation to patch up her intestines as they were perforated.

Strong doses of antibiotics, administered intravenously over a long period of time, meant to be life-saving, were not working, says Dr. Suriyarachchi, explaining that Anusha’s condition was worsening. The sutures on the cut were opening up and this entailed another operation.

Strong doses of antibiotics, administered intravenously over a long period of time, meant to be life-saving, were not working, says Dr. Suriyarachchi, explaining that Anusha’s condition was worsening. The sutures on the cut were opening up and this entailed another operation.

In desperation, as life was slipping out of the girl, Dr. Suriyarachchi called colleague and Head of LRH’s Dermatology Unit, Prof. Jayamini Seneviratne. This was because skin issues could be part of the earlier diagnosis of SLE. The sight that greeted Consultant Dermatologist, Prof. Seneviratne was terrible – Anusha lay on her bed with a burst-open abdomen and the intestines spilling out.

Dr. Suriyarachchi had said that he was facing “a blank wall”, says Prof. Seneviratne who felt that he was “facing nothing short of Mount Everest”. And the child was dying.

With the skin of the child changing due to a prolonged hospital-stay and also poor skin-care even earlier, known as “unwashed dermatitis”, he sat down to reconstruct the original diagnosis and try to get the case history from Anusha’s sister.

“Piece by piece, the evidence was evaluated,” says Prof. Seneviratne, pointing out that a fundamental feature had been overlooked at the earlier tertiary-care hospital.

In established SLE, it is frequently the skin disease which is mainly investigated. However, when positive it is not unique only to SLE but could be a feature in many other conditions as well, he says.

For two hours, he pondered — away from his busy Skin Clinic where he treats hundreds of little ones each day — going over the clues which were a “perplexing fever” despite the administration of antibiotics long-term, the “severity of the inflammation of the intestines” despite three major surgical interventions and the lack of evidence to support SLE.

The possibility of the inflammation coming from the girl’s own body, brought enlightenment as Prof. Seneviratne grappled with the likelihood of the disease being the rare ‘Familial Mediterranean Fever’, to his knowledge not reported in Sri Lanka before.

The “life and death” decision was in the expert hands of Prof. Seneviratne. If he treated Anusha for Familial Mediterranean Fever and she recovered, well and good but if she died he would have to take responsibility and suffer the consequences because he was also challenging a different diagnosis.

For, Familial Mediterranean Fever, the answer was the medication, Colchicine. Just two doses of the medication and the child who was spread-eagled on the LRH bed with burst-open tummy, was now happily munching a bun.

When Prof. Seneviratne visited her with dread in his heart about the outcome of his diagnosis and treatment, there was only immense joy for a job well-done.

(*Name changed to protect identity)

| Accurate clinical diagnosis The ‘miracle’ of saving a dying child afflicted with a rare condition was based on an accurate clinical diagnosis with solid evidence as its foundation, while keeping abreast of emerging patterns. It was not based on a battery of tests, it is learnt. The young life was saved as all specialties in government hospitals work in tandem for the benefit of patients, stresses Prof. Seneviratne, citing the example of Consultant Surgeon Dr. Chandima Suriyarachchi, when facing a blank wall, without a second thought, calling on other fields of expertise. Familial Mediterranean Fever falls into the group of ‘auto-inflammatory disorders’ characterised by:

These disorders confuse doctors because when they breakout they are very severe but may quickly resolve on their own only to flare-up again, says Prof. Seneviratne, explaining that they involve the regulatory molecules of inflammation — TNF alpha and Interleukin 1 of the immune system. In about 20% of patients with Familial Mediterranean Fever there is a ‘false positive’ when tested for dsDNA which is found in SLE. But for Prof. Seneviratne, the lack of skin lesions pointed the way to an early diagnosis. | |

Tablets from kaduru  Kaduru fruit What saved Anusha from certain death was a three-pronged attack with Colchicine, derived from the humble kaduru. Coming in tablet form and administered orally, Colchicine falls into the ‘orphan’ category of drugs which are not frequently required or used. The “attack” by Colchicine, according to Prof. Seneviratne included: Relieving the problems that were assailing Anusha because of the Familial Mediterranean Fever; preventing further attacks by this disease; and preventing amyloid deposits which would impact on her kidneys causing renal failure. Anusha has to be on Colchicine for the rest of her life. | |