When the pain lingers

Excruciating and agonising is the pain. It is also ‘very real’. The pain is there but no limb, for it has been amputated.

This is ‘Phantom Limb Syndrome’, says Consultant Anaesthetist Dr. Senaka Weerakoon of the Lady Ridgeway Hospital for Children who is also President of the Faculty of Pain Medicine of the College of Anaesthetists & Intensivists of Sri Lanka.

Dr. Senaka Weerakoon

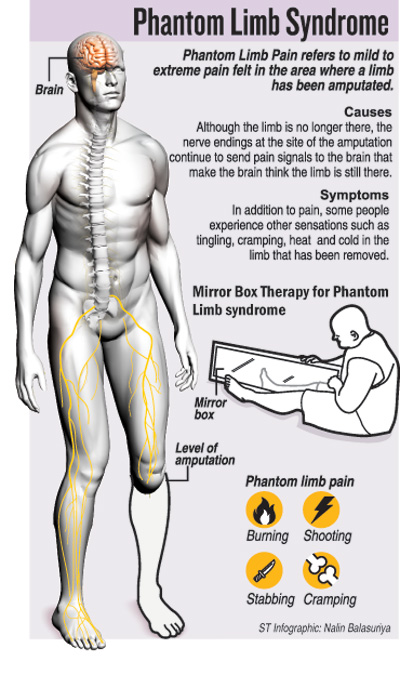

Explaining the trauma that patients suffering from Phantom Limb Syndrome undergo, Dr. Weerakoon says that they may feel a range of sensations such as crushing, stabbing, shooting/shocking, cramping, burning, throbbing, squeezing tightly, touching or even as if the limb that is no more is in an unnatural position.

These are all part and parcel of what is also felt by chronic pain sufferers, he says describing the emotional evocation of such pain by a cancer patient at Maharagama a while ago.

And these sensations are not only felt beyond the amputated limb, MediScene learns but also after such operations as a breast-removal or intestinal surgery.

First reported way back in the early-1500s in France, Phantom Limb Syndrome could affect those in any age-group, be it young or old; both genders, male or female; and in any amputation including fingers, toes, hands, legs etc. “It is very common,” points out Dr. Weerakoon referring to studies worldwide which show that 70% of all amputees are prone to Phantom Limb Syndrome soon after surgery, which gradually subsides over time. Although time is a great healer, about 6% of amputees continue to feel the pain.

Phantom Pain Syndrome has three categories:

Phantom Pain Syndrome has three categories:

Phantom pain which could manifest in the form of crushing, stabbing, shooting/shocking, cramping, burning, throbbing or squeezing tightly which engulfs the area beyond the amputation.

Phantom sensation including a tingling, pricking, numbness, feeling of hot or cold or movement, even though a limb has been amputated.

Stump pain felt at the stump of the limb.

Describing how Phantom Pain Syndrome comes about, Dr. Weerakoon says that it is due to changes in the neurological pathways at the periphery (amputated limb) as well as the centre (spinal cord and brain).

When a limb or other part is amputated, there is a sprouting of nerve-endings at the amputation site, which continue to fire stimuli to the brain. This means that these nerve-endings keep sending signals along the pain pathways to the brain through the spinal cord that the limb is still there, according to Dr. Weerakoon, who also explains that different areas of the brain have neurological links and controls over different parts of the body.

Usually what happens is that the cortex (the area of specialization within the brain dedicated to higher functions) responds with an inhibitory reaction, he says, adding that, however, in the case of an amputated limb or even chronic pain, this reaction is missing. So the periphery (amputated limb area) keeps firing off stimuli to the centre (brain), but there is no warding off of those stimuli from the centre.

“After an amputation, the cortex level controls are reorganized,” says this Consultant Anaesthetist, citing the example of an arm amputation, after which the area in the cortex which controls the face and the shoulder reorganizes itself and takes over. But as there are no inhibitory impulses emanating from the earlier control area of the brain, there is no control of the pain in the amputated arm.

Two types of factors, internal and external, could make patients more vulnerable to Phantom Limb Syndrome, MediScene understands. They are:

Internal factors – genetic preponderance, anxiety or emotional distress, attention or distraction and other diseases which bring about chronic pain.

External factors – persisting pain of the limb prior to amputation, infection of the limb-stump, non-healing wounds after the amputation, formation of neuromas (a benign growth of nerve tissue) at the site of the amputation, weather changes (hot or cold), touching of the stump, use of prosthesis (artificial limbs), rehabilitation process and type of anaesthesia that is administered during the amputation.

| Prevention and treatmentPrevention of Phantom Limb Syndrome lies in the administration of analgesics (pain-killers), says Dr. Weerakoon, referring to international research. Epidural (spinal) analgesics administered 48 hours prior to surgical amputation and continued intra-operatively (during surgery) and for three to five days post-surgery can prevent this syndrome, he says. If, however, a patient is assailed by Phantom Limb Syndrome, the treatment revolves around pharmacological, non-pharmacological and psychosocial interventions, according to Dr. Weerakoon. n Pharmacological interventions: Various groups of drugs such as tricyclic anti-depressants, anti-convulsants, opioids and local anaesthetics. n Non-pharmacological interventions: This could either be surgical or non-surgical. The surgical interventions could be to remove the neuromas that have formed at the amputation site; revision of the stump; tractotomy (severing of nerve tracts); rhizotomy (selective destruction of a problematic nerve root in the spinal cord); cordoctomy (cutting of spinal pathways in the spinal cord); dorsal column stimulation; and brain stimulation. The non-surgical interventions include acupuncture; transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS); hypnosis; massaging; and application of ultrasound. Another non-surgical intervention is Mirror Box Therapy used to stimulate the brain. Under this therapy, according to Dr. Weerakoon, the patient is told to place the good limb into one side and the stump into the other in a box with two mirrors in the centre (one facing each way). Thereafter, the patient looks into the mirror on the side with the good limb and makes ‘mirror symmetric’ movements, like when a person claps his hands. When the patient sees the reflected image of the good leg moving, it appears as if the phantom limb is also moving. With this artificial visual feedback, the patient is able to ‘move’ the phantom limb from potentially painful positions, he says. nPsychosocial interventions: There should be pre-surgical conditioning of the patient about the loss of the limb, while also mobilizing family support and training the family to deal with the situation. | |

| Pain managementStressing that the treatment of Phantom Limb Syndrome should be by a multidisciplinary team, Dr. Weerakoon says that it should include Pain Specialists, Anaesthetists, Surgeons, Psychiatrists, Physiotherapists and Occupational Therapists. Those not only with Phantom Limb Syndrome but also suffering from chronic pain can seek help at the Pain Clinics at the National Hospital in Colombo, the Kandy Teaching Hospital, the Anuradhapura Teaching Hospital and the Badulla Hospital. There is also a Pain Clinic at the Army Hospital at Narahenpita which can be accessed by army personnel and their families, it is learnt. |