News

Abortions: No accurate figures because it is underground

Abortion in Sri Lanka is illegal, except when a pregnancy endangers the life of the mother. Yet it is also recurrent and widespread. Ever since the Government closed down abortion clinics in 2007—including a popular UNFPA-funded outfit in the heart of Colombo—women have gone underground to terminate unwanted pregnancies.

Abortion in Sri Lanka is illegal, except when a pregnancy endangers the life of the mother. Yet it is also recurrent and widespread. Ever since the Government closed down abortion clinics in 2007—including a popular UNFPA-funded outfit in the heart of Colombo—women have gone underground to terminate unwanted pregnancies.

There are no recent statistics on how many abortions are carried out. This week, media reported the number at 658 per day—a staggering 240,170 per year. But medical experts cautioned that this was an old estimate dating back to a study first conducted in the late 1990s by Prof. Lalani C. Rajapaka, an expert in community medicine.

“It is erroneous to quote that figure now,” Prof. Rajapaksa told the Sunday Times. “You need a new figure because the prevalence in 1997 is not applicable to 2016.”

It is unrealistic to assume that there were 250,000 abortions per year, contends Dr. Kapila Jayaratne, a public health specialist at the Government-run Family Health Bureau. This is because, on average, there are around 350,000 annual live births (it was 349,750 in 2014).

Abortion is notoriously difficult to map because of the stigma and secrecy associated with it. But certain hypotheses have been drawn from recent research related to maternal mortality and post-abortion hospital admissions. Even these do not reveal the full picture.

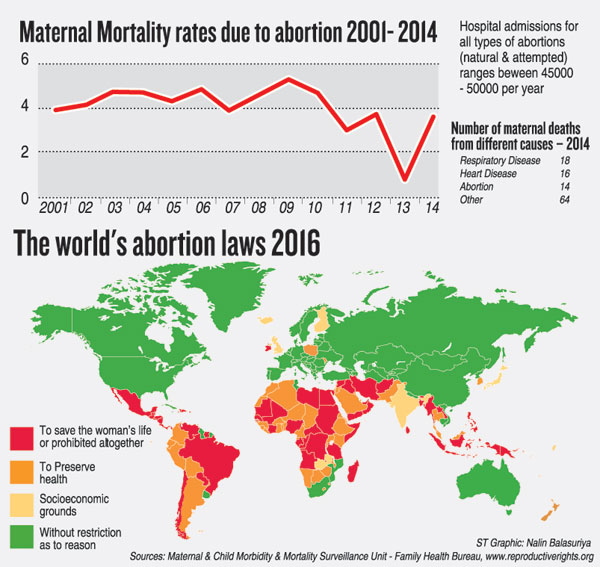

For instance, Dr. Jayaratne—who is in charge of maternal and child morbidity and mortality surveillance at FHB—has analysed maternal mortality between 2001 and 2014. This refers to the death of a woman during pregnancy or within 42 days of termination of the pregnancy.

Sri Lanka has recorded remarkable success in limiting maternal mortality. Thus, in 2014, there were 112 maternal deaths reported from across the country. A large majority of the deceased were from the rural (65%) or estate (10%) sectors, the FHB observes. The third most common cause of death was abortion. There were also suicides to consider; it is not known how many of them were prompted by unwanted pregnancies.

Some conclusions have also been drawn from the number of abortion-related hospital admissions. “Hospital admissions for all types of abortions, natural and attempted, range from 45,000 to 50,000 per year,” said Dr. Jayaratne. “This is the tip of the iceberg.” Private sector admissions are not included. Also not reflected are those who self-abort by buying unregistered drugs used for medical abortion—mifepristone and misoprostol.

Dr. Carukshi Arambepola and Prof. Rajapaksa are behind the most recent investigations on abortions. Their report, titled “Decision making on unsafe abortions in Sri Lanka: a case-control study”, was published in December 2014 and is available online for citing.

The researchers interviewed 171 women admitted to nine hospitals in eight districts following an unsafe abortion. The controls were 600 post-partum mothers. The study finds that 46% of those who had undergone unsafe abortions had visited the abortionist more than twice and 14% more than five times.

“In the majority of cases, septic procedures with no pain relief were performed during termination by non-qualified abortionists, for a wide range of payment of Rs. 1,000-30,000”, it states. “In the qualitative inquiry, women reported that most places lacked sterile or proper equipment and were run without assistance in the back room of a boutique, own home or in the house of a relative or abortionist.”

“None took place in Government hospitals or clinics run by non-governmental organisations,” it observes. “The most commonly used methods were trans-vaginal insertion of rods and injections. The worst experience reported in the qualitative inquiry was one woman collapsing following the insertion of a castor oil plant stem into the vagina for a fee of Rs. 30,000.”

Interestingly, when asked about future intentions, 14% of cases alleged they would resort to abortion in the event of another unwanted pregnancy, while 47.5% were not sure of their decision. The report does not attempt to gauge the number of abortions taking place but does provide a profile of the types of women seeking terminations: “The majority of women in both groups belonged to 25-29 age group, were married and of Sinhala-Buddhist origin.”

There was consensus among all experts interviewed for this article that women who sought or underwent abortions were predominantly married and in their thirties or older. “The most common reason for termination of pregnancy was that they had enough children and had completed their family or their last child was too small,” said Dr. Mangala Dissanayake, Consultant Gynaecologist at Panadura Base Hospital and Chairman of the Subcommittee on Abortion.

This indicated that abortion continues to be used in Sri Lanka as a means of family planning. But medical experts and like-minded academics this week renewed a call for a reform of laws to allow abortion in cases of rape, incest and congenital abnormalities.

Dr. Gihan Abeywardena, Consultant Psychiatrist at the Kurunegala Teaching Hospital, has long advocated a change in the laws. This is because many victims of rape and incest are referred to him every month. And in recent years, he has seen an increase in the number of mentally challenged children and women who fall pregnant as a result of sexual abuse.

“They are easy prey and can be easily manipulated,” he said. “I come across quite a few girls, both in Kurunegala and Matale—two or three a month. Most of them come to us pregnant. Some are not pregnant. It is quite a difficult situation because the legal age of consent in Sri Lanka is 16. Even when these women are above the age of consent, they have a mental age of a minor.”

“We find it very difficult to convince the law that the baby should be aborted,” he continued. “The unfortunate girls have to continue with the pregnancy and give birth. Recently, a 20-year-old mentally challenged woman was sent to him. She had no schooling and could not read or write. She lived at home with her parents.

An uncle, a relation of the family, earned the trust of the parents and offered to watch the child. Whenever they went out of the house to run an errand, he would abuse her and threaten to kill her if she told her mother or father. “She was tested for abdominal pain and found to be pregnant,” Dr. Dissanayake said. “Neither she nor the parents had known. She was confused and perplexed. She didn’t even know what it meant to be pregnant.”

The woman was well beyond 12 weeks when Dr. Dissanayake saw her. “Any obstetrician will hesitate to go ahead with an abortion over 12 weeks, not for lack of competence but because the risk to the mother is more. She was forced to continue with the pregnancy. The stigma forced the family to relocate from their remote village. It is an unfortunate incident which is quite common.”

Many doctors said they had three or four requests every month from women who wanted to end their pregnancies. They are usually turned away because the law does not allow it. This was true also of mothers who were carrying children with severe congenital abnormalities, including babies who were certain to die near or upon delivery.

Attempts have been made since the 1970s to amend the law, the most recent in 2012 by the then Child Development and Women’s Affairs Minister Tissa Karaliyadda. But the Catholic and Buddhist clergy have always opposed it, even in cases of rape, incest and congenital abnormalities. To succeed this time will take a solid argument backed up by solid new research—something that is glaringly lacking at present.