Remembering the “gala time”

View(s):

File picture of an apparel factory. Garments exports is the saving grace of an economy that is suffering from a shortage of foreign exchange

By March 2009, Sri Lanka was at the doorstep of a foreign exchange crisis. Official foreign exchange reserves had dropped to US$ 1.2 billion, while it was enough to finance just 5 weeks of imports. As investor confidence had also deteriorated, Sri Lanka was not in a position to borrow either. It was the last days of the 30-year long separatist war. Externally, the country had faced rising oil and food prices in the world market, which was followed by the US financial crisis. The government had requested IMF help, but the IMF decision to help was dragged for months. In fact, IMF had already shut down its Sri Lanka office two years ago in 2007.

Finally, the IMF came with its rescue mission in July 2009 – a Stand-By Arrangement amounting to $2.6 billion that was disbursed in eight tranches in 20 months. The IMF commitment with the Stand-By Arrangement was followed by an upsurge in capital inflows largely as financial investments in government securities, including the newly initiated commercial borrowings through US$-denominated international sovereign bonds (ISBs).

“Gala time”

And, since then Sri Lanka had a gala time! For the September 2009 issue of the Economic Review magazine published by the People’s Bank, I wrote on “Gala time in rainy days”. The respite with the IMF help could be “temporary and dangerous as the highly volatile capital inflows could also reverse suddenly dragging the balance of payments into the same problem” unless and until Sri Lanka embarks on reforms.

Even before that, I had revealed how Sri Lanka was “heading towards a Foreign Exchange Problem” published in the Sunday Times on November 2, 2008. Although the country had a growing trade deficit which increased from 8 per cent of GDP to 15 per cent during 2003-2008, the problem was hidden under the carpet! Fast-growing foreign worker’s remittance flows and the government’s foreign borrowings cushioned the growing trade deficit. It was further supported by increased tourist incomes after the end of the war and the renewed credit worthiness of the country after the IMF Stand-by Arrangement.

Yes; then, we had a real gala time! We made every possible effort to borrow and continued to borrow and spend. We had opened our Treasury Bond and Treasury Bill markets for foreign investment in 2007 and in 2008. We had also commenced commercial borrowings in 2007 by issuing international sovereign bonds (ISBs). In 12 years, the commercial foreign borrowings through ISBs accumulated from $0.5 billion in 2007 to $17,500 billion in 2019 with maturity period being five or 10 years. We made investments which would bring “returns” in 20 – 25 years’ time, but that is also only if we can make them productive. All our public investment projects were “credit-financed” projects. Mega projects did not generate medium-term returns, but we had to start repaying our foreign borrowings with interest for which we borrowed again!

Yes; then, we had a real gala time! We made every possible effort to borrow and continued to borrow and spend. We had opened our Treasury Bond and Treasury Bill markets for foreign investment in 2007 and in 2008. We had also commenced commercial borrowings in 2007 by issuing international sovereign bonds (ISBs). In 12 years, the commercial foreign borrowings through ISBs accumulated from $0.5 billion in 2007 to $17,500 billion in 2019 with maturity period being five or 10 years. We made investments which would bring “returns” in 20 – 25 years’ time, but that is also only if we can make them productive. All our public investment projects were “credit-financed” projects. Mega projects did not generate medium-term returns, but we had to start repaying our foreign borrowings with interest for which we borrowed again!

Reforms: for whom?

The IMF Standby Arrangement came along with the key objective of “economic reforms” to strengthen the fiscal position, to build foreign exchange reserves and, to support post-conflict reconstruction and relief programme. The latter was carried out, but there were no economic reforms, which required the first two. The stock of foreign exchange reserves was dwindling along with a worsening government finance position and foreign exchange position.

Finally, we asked the IMF again in 2016. This time IMF approved a three-year Extended Fund Facility (EFF) of $1.5 billion aiming at resolving the emerging foreign exchange problem and at supporting the government’s economic reform agenda. As the reform agenda didn’t continue as expected, Sri Lanka lost the last tranche of the EFF which was due in 2019.

Now as we approach the end of 2021, the most recent reports indicate that the official forex reserves are down to $1.6 billion. This is no surprise as the country was heading towards that position since 2009, or even before that, by postponing economic reforms. The difference is that the government has chosen so far not to go to the IMF to ask for a rescue mission, but to other countries which may not require conditions for “reforms”. At least for “a few dollars more”, the revival of tourism or the arrival of a few foreign investment projects are yet to be seen. Until it happens, perhaps, the only option available is to look for bilateral assistance as the government continues to do.

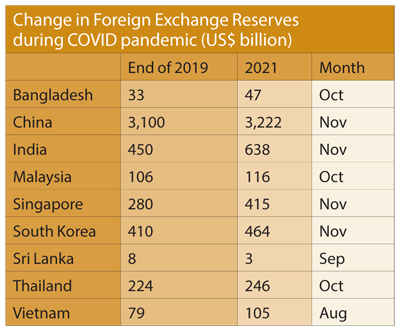

During the period of COVID pandemic, as the aggregate demand was lower and world prices were lower, most of the emerging economies in Asia were able to build up their foreign exchange reserves. But Sri Lanka was unable to finance even its reduced import bill, so the country had to resort to import controls. Besides, the post-2009 “gala time” had come to an end so that it was time to pay for that with $4 – 5 billion a year as repayment of foreign loans.

Why are we here, today?

The main problem was the abandoning or the denial of the two main sources of foreign exchange earnings – exports and foreign direct investment (FDI). The former is strongly associated with the latter because rapid export growth is a result of FDI inflows. It is absolutely fascinating to think that at a time when FDI flows to Asian countries were growing exponentially, why was Sri Lanka overlooked? Even in the midst of COVID-19 pandemic issue, India received $64 billion FDI and Singapore $90 billion FDI while Sri Lanka could attract only less than $0.5 billion! If it was the separatist war that kept investors away from Sri Lanka, now it is a valid question to ask why they have avoided Sri Lanka over the past decade after 2009 when the country was peaceful.

The main problem was the abandoning or the denial of the two main sources of foreign exchange earnings – exports and foreign direct investment (FDI). The former is strongly associated with the latter because rapid export growth is a result of FDI inflows. It is absolutely fascinating to think that at a time when FDI flows to Asian countries were growing exponentially, why was Sri Lanka overlooked? Even in the midst of COVID-19 pandemic issue, India received $64 billion FDI and Singapore $90 billion FDI while Sri Lanka could attract only less than $0.5 billion! If it was the separatist war that kept investors away from Sri Lanka, now it is a valid question to ask why they have avoided Sri Lanka over the past decade after 2009 when the country was peaceful.

The export problem was hidden under worker remittances and tourism expansion. An increased migration for foreign work was not a sign of prosperity, but that of poverty and misery; the country was not able to offer better jobs and better rewards to its citizens so that they find it better to leave the country than to stay and suffer. But it was politically attractive, because it generated foreign exchange inflows as big as $6 – 7 billion a year and reduced the unemployment problem at home. The rise of tourist arrivals during the post-conflict time period generating about $4–5 billion a year was, apparently, automatic, while economic policy initiatives had little to do with that. In the face of both, Sri Lanka overlooked the importance of export promotion.

The second problem came with increased short-term borrowings or portfolio investment. Such portfolio investments flowed into the stock market and the newly-opened capital markets were, apparently volatile compared with more stable long-term FDI. As expected, portfolio investments left the country as they all foresaw the dangerous foreign exchange market volatility as early as in April-May 2020.

It is good that the deep-rooted issues of the forex problem were finally exposed whether we would choose to accept it or not. It’s a result of ignoring the reforms. And reforms are necessary, not because the IMF wanted them, but because the country wanted them. Even after we know the truth, whether we accept it or not is a matter of choice!

(The writer is a Professor of Economics at the University of Colombo and can be reached at

sirimal@econ.cmb.ac.lk and follow on Twitter @SirimalAshoka).

Hitad.lk has you covered with quality used or brand new cars for sale that are budget friendly yet reliable! Now is the time to sell your old ride for something more attractive to today's modern automotive market demands. Browse through our selection of affordable options now on Hitad.lk before deciding on what will work best for you!