News

Electric shocks killing jumbos by the dozen

View(s):

An elephant suspected to have died of electrocution was found in Vavuniya last week

By Malaka Rodrigo

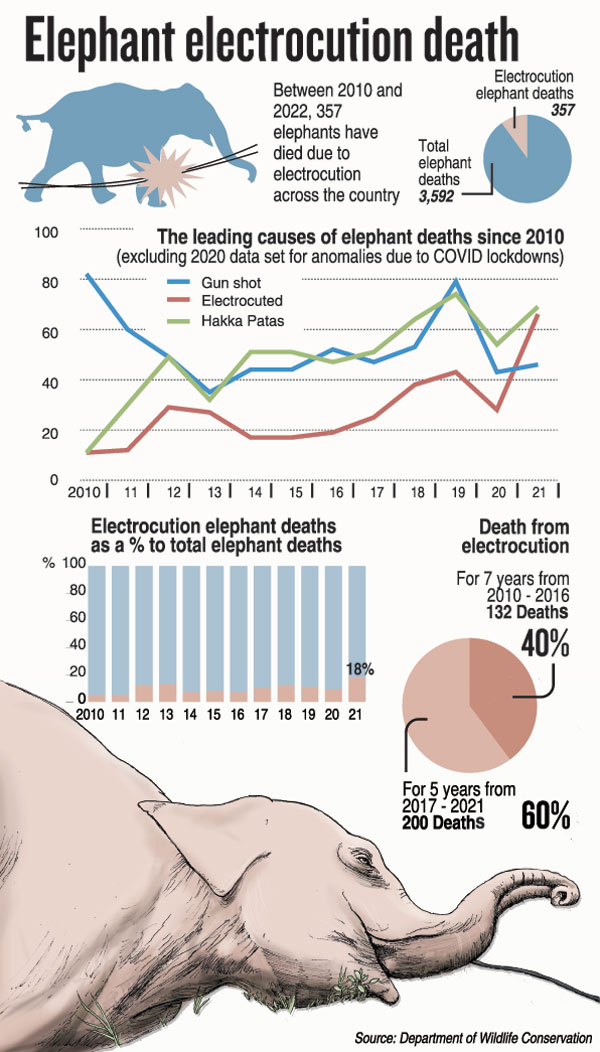

Just this week, three elephants, including a tusker and a calf, died from electrocution in Mihintale. One tusker was only about 15 years old, and the calf was about five years, according to sources of the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC).

Mid week, another elephant died of electrocution in Vavuniya and at the start of the month, a Kalawewa tusker named Barana also died from electrocution.

As of the first week of August, 258 elephants have died and more than 50 humans have lost their lives.

Gunshots have accounted for 35 elephant deaths, while ‘hakkapatas’, or jaw bombs, have killed 30.

Worryingly, electrocutions have killed 25 elephants.

This has become the third main reason for elephant deaths. This threat must be addressed environmentalists say.

In 2010, only 11 elephant deaths out of 227 were due to electrocutions, but in 2021, electrocutions killed 66 elephants, compared with ‘hakkapatas’, which killed 69 elephants.

In 2010, electrocutions accounted for only 4% out of the total 227 elephant deaths that year, but in 2021 it accounted for 18% of 375 deaths.

The tusker Barana was killed recently, and Revatha was killed last year due to electrocution.

Fences protecting farmland are linked to the main electricity lines. An electric fence is powered by an energiser, which converts mains electricity or that from a 12V car battery to a high voltage (6000-9000 V) low amperage (around 100 mAmps) DC pulse of about 1 per second. Such fences give a tremendous ‘shock’ on contact, but do not cause any harm. Connecting the mains electricity or an inverter to a fence means it carries a continuous current of 240V 5 Amps AC.

Dr. Prithviraj Fernando, an elephant biologist, said the electric shock interferes with the heart rhythm and causes burns and damage to internal organs. “It is illegal to set up such lethal fences, or power lines. Any animal coming into contact with such fences will get killed.’’

The majestic Barana died of electrocution recently. Pic by Milinda Wattegedara

The DWC Director General Chandana Sooriyabandara said suspects are arrested.

But often, those responsible plead guilty and pay the Rs 500,000 fine for killing an elephant. It is also illegal to get electricity from the national grid without approval, but the penalty is not enough, he said.

Mr. Sooriyabandara said that there are those who are involved in farming who link their fences to the main grid.

DWC former Director General Sumith Pilapitiya, told the Sunday Times, that electrocutions are prevalent in areas where the human elephant conflict is high and the houses and farmlands are connected to the electricity grid. “Connecting a household electrical supply directly to a fence is illegal, so both the electricity board and the DWC can take action.’’

Dr Fernando said that judging by the data, electrocution is becoming a method of choice for killing elephants. “Culprits linked to shootings, or the use of ‘hakkapatas’ may be difficult to find, but it is not the case with electrocutions as the elephant is often found fallen near the fence, so authorities can easily apprehend the person responsible. If all were apprehended, charged, prosecuted, and penalised, what it reflects is that the penalty for such action is not a deterrent, so it is important to raise penalties.

“But, more importantly, Sri Lanka needs to have a system of detection and prosecution, not waiting till another elephant death occurs.’’

Dr Pilapitiya said: “In addition to significantly increasing the penalties for illegally connecting household electricity to their fences, there are other measures that can be taken. I feel that DWC should work with CEB and reach an agreement that if any person illegally connects their household electricity supply to a fence and kills an elephant, the CEB will disconnect their household electricity supply for 10 years. Regulations may have to be amended, but I think this will be a much more effective deterrent than what is available at present.

“Ideally checks should be done in areas with grid connected electricity where there are agricultural lands near households with grid electricity to see if there are power lines connected directly to the fences. By such checks, we can prevent possible electrocutions, which is much better than penalising people after the elephant is dead.’’

The DWC does not have enough staff to check fencing, but it could work with the CEB to get the services of meter readers to do that job, he said.

It was heard in the Committee on Public Enterprises hearings that meter readers are getting paid an additional incentive for providing accurate readings, Dr. Pilapitiya said.

Sri Lanka has the highest Asian elephant (Elephas maximus maximus) density in the world, but 70% of the wild elephants roaming outside protected areas create conflict with people. The 2011 survey shows Sri Lanka is home to about 6,500 elephants But, statistics indicate that from 2010 to the present, over 3,500 elephants have been killed. Most are victims of the HEC. More than 1,100 people also have lost their lives.

Soon after Gotabaya Rajapaksa became president, he set up a committee involving the leading elephant biologists, conservationists, Government, and other conservation agencies to propose a strategic plan related to HEC. A plan was handed over to him in 2020, but recommendations were not adopted.

Dr Pilapitiya said that “if the Government implements the plan, even on a district-by-district basis, I am very confident that we can get the conflict under control in a few years’’.

The best way to say that you found the home of your dreams is by finding it on Hitad.lk. We have listings for apartments for sale or rent in Sri Lanka, no matter what locale you're looking for! Whether you live in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Matara, Jaffna and more - we've got them all!