Beling connection and fragmented memories of Wendt

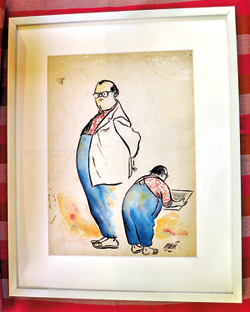

Wendt in Fragments: Deborah Philip giving her talk at the Harold Peiris Gallery earlier this month. Pix by Eshan Fernando

Deborah Philip was born to ‘the people in-between’, a phrase borrowed from Michael Roberts’s landmark book and one that has obsessed her. After schooling at CMS Ladies’ College, she would go to Colombo University where she fell in love with the History Department there (challenging the ‘grand narratives’ of chronicles and heroes and debunking good old nostalgia).

Today she is a PhD student at the City University of New York, working on a thesis about her own community, the Burghers.

In her aunt’s dark Dehiwela house with the smell of the sea and wicker chairs with cushions, a ginger cat and lots of family mementos, we sit down to talk about Deborah’s recent ‘highlight’ in Colombo — her well-attended talk at the Lionel Wendt titled, Wendt in Fragments (in tandem with the exhibition Wendt on Wendt), where she was allowed to indulge to the hilt in her passion for the colonial period and race and class in British Ceylon.

It all began because of her grandfather – the artist Geoffrey Beling, whom Deborah knew till her fourth year; bright but brief memories of breakfasts with him or maybe a shared afternoon on the verandah at Layard’s Road but alas, no reminiscences of his art.

A section of the audience

When she talked of her grandfather and the fragmented pieces of memories of Wendt, good friends who together formed part of the ‘43 Group, Deborah drew on written records, anecdotes, artworks, photographs and other material objects.

It was in 2004, when the tsunami threatened the littoral and the waves reached ankle-high in Deborah’s garden in Dehiwela, that the 16-year-old thought seriously of safeguarding the ‘archives’ or the letters and mementos left behind by Beling and cherished by others including Deborah’s mother.

The letters and documents alone could not put together much so Deborah had to resort to the books by Manel Fonseka and Neville Weeraratne, and the retentive memory of Damayanti Peiris – Harold Peiris’s daughter, in trying to form a full-blooded image.

At first it was the letters that intrigued her but soon the whole cornucopia of things grew on her and she cherished catalogues and books with inscribed overleaves. She kept them sorted in shirt boxes. With the distance in time they all acquired more patina.

It was, however, all in fragments and the complete picture seemed impossible to focus on.

The most important discovery she made is an architectural blueprint by Beling showing details of the Lionel Wendt theatre’s ceiling.

In her collection

This, she says is the first tangible proof that Beling did actually have a hand in designing the Wendt – given that he had to abandon his training as an architect in India when his father passed away.

From this intriguing blueprint Deborah turned towards the fascinating matter of Colombo’s changing landscapes as Independence approached – the Wendt being one of the first buildings to break from the colonial mould.

Another fascinating aspect she explores is the financially not so secure position of Beling but also Keyt, who both had to worry about exhibition costs.

This led her further into the territory of the ambivalent position of the Burghers. They had access to English and what Deborah calls ‘cultural capital’ but were far from being elites, as the Burghers as a community are sometimes presented with a broad brush.

As the people in-between they were very ‘aspirational’ and while it is true that some of them had anti-colonial leanings, as a group they wanted pretty much to be the ‘wheels of the Empire’ and moulded themselves on the British.

Central to Deborah’s work are the albums of Beling’s photography which she sensitively interpreted. The albums are curious in that they have sepia images of family and friends as well as others not named.

Deborah spoke about the recurrence in images of the piano and the camera, mostly a tripod, which she uses to point out the aspirations of the Burghers and their place that is ‘outside the nation’. No wonder, she concludes, that they were the first community to ‘get up and leave’ two decades later, when Sinhalese nationalism raised its head.

Deborah says she is grateful to the works of Anoma Peiris, Nihal Perera and James Duncan, in her research.

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.