Remembering the Football War at World Cup

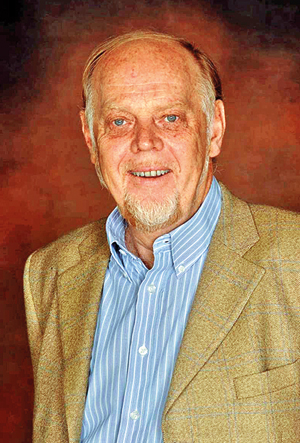

Former South African Ambassador to Poland and Chile Victor Zazeraj

In our part of the world it’s with cricket that passions ignite. Quite literally sometimes, as in the 1996 world cup semifinal between India and Sri Lanka where disappointed Indian fans set fire to sections of the stand at the Eden Gardens ground in Calcutta. Similarly with national feelings stirred following clashes between Pakistani and Afghan fans in Sharjah, Afghans took to the streets in Kabul to celebrate Sri Lanka’s 2022 Asia Cup Victory over Pakistan.

In a wider context national anger has been aroused by incidents like the persistent no balling of Sri Lanka’s ace weapon Muttiah Muralidaran by Australian Umpire Darrell Hair. The under arm ball by Trevor Chappell to deny New Zealand a chance of a last ball tie result is another example. Still perhaps the most famous cricketing episode to fuel national resentment remains the 1932-33 Ashes Test Series in Australia where dangerous bodyline bowling by the English team escalated into a diplomatic incident. The affair was taken up at the highest levels of Government with even discussion of impacts on trade relations between the countries.

But football takes passions to a different level. As the Qatar FIFA World cup swings into full gear, being someone with only a limited interest in football, I can still absorb the excitement. The event revives memories of the techniques and tactics of the Germans, the dazzling skill of the Brazilians and for those that favor the underdog there is Cameroon the first African team to reach the quarter finals of the world cup in 1991. They surprised opponents with impromptu moves, African agility and even defeated the then reigning champions Argentina.

Acknowledging that the FIFA World Cup is an exciting global event is easy. Digesting that FIFA World cup qualifying matches could trigger a war is more challenging. That happened between Honduras and El Salvador in 1969 and was chronicled by Polish Journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski in his book ‘The Soccer War.’ For a strong insight I interviewed former South African Ambassador to Poland and Chile Victor Zazeraj. He is an aficionado of Kapuscinski:

Victor, lets first approach the cultural context. You have lived and worked in Europe, Africa and Latin America. Is there a difference in how football is viewed in Latin America?

There is a marked difference. While football passion is evident in Africa and Europe, it manifests less vigorously than in Latin America. Europe has its share of football hooligans, and I’m not sure that qualifies as passion. The financial power of European football is unrivalled. It is a multibillion dollar entertainment industry, combining tribal, regional, and national loyalties going back generations. It is an extraordinary social phenomenon.

Africa is much more exuberant, where love of the game is expressed in joyous ways and conflict is almost unheard of.

Latin America takes it to a different level. Brazil is Latin America’s and indeed football’s most successful nation with more World Cup victories than any other team. As football-crazy as their neighbours, they also bring humour and party atmosphere to the game. In 2006 I happened to be in Brasilia on the day of the national team’s first World Cup match in Germany. It was much like the Africa. The civil service was given the day off to watch the match, people drove around the capital city hooting, shouting, and singing. President Lula da Silva expressed a mild concern, suggesting their iconic goal-scorer Ronaldo had become “too fat”. Ronaldo retorted from Germany that Lula was “a drunkard”, which for an outsider pretty much summed up the Brazilian approach to what the famous Pele called “the beautiful game”. But football fervour sometimes tests the imagination. When Brazil defeated England in a World Cup encounter, an article with the headline “Jesus Defends Brazil” appeared in the Rio de Janeiro paper ‘Jornal dos Sportes’ explaining that “whenever the ball flew towards our goal and a score seemed inevitable, Jesus reached his foot out of the clouds and cleared the ball”. This possibly illustrates the nature of football passions in Latin America.

Now let me direct your focus to the football war. Understand that although football may have exacerbated matters, there were other strong underlying issues in the war between Honduras and El Salvador?

Indeed. Tensions along the border between El Salavdor and Honduras had almost reached breaking point before the football matches that triggered the war. It had to do with migration, and lack of sufficient land to sustain peasant farmers. Overpopulation on the El Salvador side led hundreds of thousands of subsistence farmers to move across to Honduras, where land was available. When Honduras tried to force them back, political temperatures started rising, and eventually it was football that provided the spark to a deadly war between the two countries.

War in any circumstances is tragic and horrifying but what happened in the three FIFA World Cup qualifying matches between El Salvador and Honduras resembles a Monty Python comedy sketch. Can you elaborate?

It did appear bizarre and comical at first. But the full extent of the tragedy became clear thanks to the masterful foreign correspondent Ryszard Kapuschinski. He was on the ground when it happened.

The Brazilian Team with Pele: Winners of 1970 World Cup in Mexico

The first match was played in Honduras. Football fanatics and provocateurs descended on the hotel of the El Salvador team on the night before the game. They kept up a racket for the whole night, banging pots and pans, breaking hotel windows by hurling stones, setting off fireworks, and making it impossible for the Salvadoran team to get any sleep. Honduras won the first match 1-0.

The return match was played a week later, in El Salvador. Matters there got out of hand. A hostile crowd surrounded the Hondurans’ hotel, breaking windows, throwing rotten eggs and dead rats, and creating general havoc. The players had to be escorted to the stadium in armoured vehicles. The Honduran flag was publicly burnt, to the unrestrained joy of the El Salvador crowd. The playing of the Honduran National Anthem was accompanied by whistling, and just about every form of disrespect imaginable. The hosts ran a dirty, tattered dishrag up the flag-pole instead of the Honduran flag. El Salvador won 3-0. At least two visiting fans were killed, scores injured, and about 150 visitor’s cars burned. The border between the two states was closed a few hours later.

The deciding game of the three match series was played in Mexico. Honduran and Salvadoran fans were separated in the stadium by 5000 armed Mexican police. El Salvador won 3-2.

What form did the war take?

On the same day of the Mexico match El Salvador severed diplomatic relations with Honduras. Weeks later their army crossed the Honduran land border and air force bombed the Honduran capital, Tegucigalpa.

The soccer war lasted 100 hours: 6000 were killed, and 12 000 wounded. 50 000 lost their homes and fields. Many villages were destroyed.

As a military campaign it was a fiasco. It ended when other Latin American states intervened, and the major world powers demanded an immediate stop to combat operations. Tensions along the border remained, and the original issues that gave rise to violent hostilities continued unresolved. The governments of both countries seemed satisfied with the outcome, although it was unclear precisely what about the outcome that satisfied them. Perhaps they felt they had made their point, whatever that was.

In conclusion Victor what do you see as the key takeaways from this conflict?

I hesitate because, as a career diplomat, student of international relations, and having been in enough combat zones I am careful about drawing easy conclusions. Things are often more complicated than they appear. That is why we are indebted to the work of Kapuschinski. He tells the story as an observer on the ground, and leaves the pontificating to others who have never been in the line of fire.

Coming from a country with a long history of racial division, I learnt early in life that language matters. Once it becomes acceptable to insult and dehumanise others, actions with ugly consequences often follow. In the case of El Salvador and Honduras, neighbours which to outsiders appear similar: sharing language, religion, and comparable histories, it seems difficult to fathom why they would kill each other over a game called soccer. In the build-up to the war, newspapers on both sides waged a campaign of hate, slander and abuse, calling each other Nazis, dwarfs, drunkards, spiders, and thieves. Predictably perhaps, shops were burned and pogroms followed. The stage was set, the atmosphere created, and war was the next step.

The 1994 genocide in Rwanda was similar. There was relentless radio propaganda calling people “cockroaches” creating an environment in which a minor spark could set off a monstrous calamity. We also saw it in the former Yugoslavia during the 1990s, where the term “ethnic cleansing” entered our vocabulary. There are many other examples that illustrate this point.

It often starts with language. There is much debate about “politically correct” language, but my point is simply about mutual respect, and taking care never to dehumanise others. Once verbal abuse becomes normalised in any society, serious trouble is likely to follow. That would be my main take away from the Soccer War.

(The interview writer works for Roelens Solicitors and has been High Commissioner to the Republics of Singapore and South Africa)