75th Independence

The coming of the Portuguese

View(s):By Murray da Silva Cosme

At the dawn of the 16th century, Colombo was not the sprawling city of today. Its modern history was just about to begin. There was no inkling then that it would blossom into the island’s premier city. It was then a well-established Moorish settlement called Kolontota also known as Kolumpura and Kolamba, which came to be called Columbo by the Portuguese.

According to Moorish tradition, in the dawn of Colombo’s history, it was one of the first of six settlements which daring Moorish traders and sailors established on the east coast of the island.

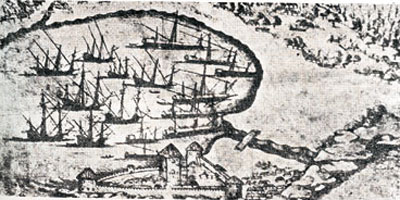

A view of the first Portuguese fort in Colombo in 1518 -- From Gaspar Correrra's 'Lendos da India'

Virtually nothing can be gleaned from the early chroniclers of pre-Portuguese Colombo. Doubtless, it is the Kao-laupu of the Chinese traveller Wang-Ta-Yuan, who visited the island in 1330, and also the Kalmepu of the famous Ibn Batuta who arrived 14 years later.

It was at Kolamba or Kolontota that King Arya Chakravarthi of Jaffna landed to wage war on the King of Kotte and it was from the same port that a Sinhala monarch had the depressing ill-fortune to be deported as a prisoner to China, while according to the Nikaya Sangrahawa, minister Alakeswara selected a site for the city of Kotte “not far from the port of Kolamba.”

The other Sinhala term Kolambo is said to be a variation of the Pali and Sanskrit Kadamba. Little value can be placed on friar Paulo de Andrade who, writing about Colombo in 1630, says the name was derived from Colahamba after a mango tree which stood on the site of the church of St. Lawrence.

November 15, 1505, was a momentous day for Kolontota for a Portuguese flotilla, after a well-deserved rest at Galle, from the furies of the Indian Ocean, dropped anchor in its port. A new chapter was being opened with History and Destiny for better and for worse for the people of this green and smiling island.

The visitors were led by Dom Lourenco de Almeida, a young man of prodigious strength, who had been detailed by his father, Dom Francisco de Almeida, the first Viceroy of Portuguese India, to blockade the sea lanes between the Maldives and Ceylon through which the Moors, in order to avoid the Portuguese, had begun to take their argosies laden with spices, drugs, silver and gold from Bengal, Siam, Malacca and the Indonesian archipelago.

Though stormy seas had blown this flotilla to Galle, doubtless sooner or later, the Portuguese would have arrived in this island as glowing reports of its natural wealth in cinnamon, pearls, precious stones and elephants had circulated in European mercantile circles after the entry of Portugal’s flag into Eastern waters.

By the time Dom Lourenco’s flotilla entered the port, Kolontota had assumed the status of an international mart and was agog with activity, by standards prevailing then of course. Ships from Bengal, Cambaya as Gujerat was called, Malacca, Ormuz and the Chomandel coast and other oriental ports were berthed cheek by jowl, some being loaded with cinnamon, copra, arecanuts and coconuts and even small elephants for Gujerat; cinnamon, masts and timber for Ormuz, from where gold, silver and cotton silk and no doubt such luxuries as perfumes and delicacies, ornaments and Persian wines were imported, while precious stones must be added to the list of exportable commodities much prized abroad.

The port which was really at the mouth of the Kelani River, affording easy access to river boats bringing cargoes from the hinterland, took its name from its natural surroundings ‘modera’; which name persists today and means mouth of the river in Sinhala, the current anglicised version Mutwal being derived from the Tamil Muhathuvaram and the Sinhala Modera.

Colombo’s beginnings have been immortalised pictorially in the famous Portuguese historian Correrra’s book ‘Lendos da India’.

The anglicised Bankshall Street in Pettah today recalls a time when the crowned heads did not scoff to indulge in trade, the name being derived from the Sinhala term ‘banga salavas’ or warehouses of the monarch of Kotte, whose cinnamon, then a royal monopoly, was stored for sale and shipment.

The part corresponding to the Fort of today was to shape into Portuguese Colombo.

The rocky promontory called Galbokka in Sinhala and Galle Buck in its anglicised form was a prominent feature of 16th century Colombo. The picturesque Beira was not a part of the landscape. It was a long time before Portuguese engineering ingenuity damned a rivulet of the Kelani to strengthen with defences of aquatic proportions.

The sight of the Portuguese flotilla struck consternation among the Moors with the anticipated loss of their virtual monopoly of the carrying trade and the Moorish-instigated Sinhala population with visions of threats to their independence, attacked a party of visitors sent ashore to forage for wood and water. A volley of retaliatory cannon balls thundered across the waters, terrifying the citizens of Colombo.

Reports to the Sinhala court at Kotte partly perpetuated and made famous in the Rajavaliya are worthy of reproduction here: “There is in our harbour of Colombo a race of people fair of skin and comely withal. They don jackets of iron and hats of iron; they rest not a minute on one place; they walk here and there.”

And with reference to their use of bread and wine, the informant said, “They eat hunks of stone and drink blood; they give two or three pieces of gold and silver for one fish or one lime; the report of their cannon is louder than the thunder when it bursts upon the rock Yugandhara; their cannon balls fly many a gawwa and shatter fortresses of granite.”

The same chronicle has it that Prince Chakrayuddha spied in disguise on the Portuguese advising Dharma Parakrama Bahu, the virtual ruler of Kotte (owing to his father Vira Parakrama Bahu being in his dotage) that it would be well to grant an audience to the visitors, whose martial exploits on the Indian coast were not unknown.

Mutual suspicions made Dom Lourenco retain hostages, while the Sinhala escorts’ attempt to screen the proximity of their capital by leading Cutrim through an elaborate, circuitous route for three days, has become of proverbial usage today in the saying “Parangiya Kotte giyawage” meaning ‘like the Portuguese going to Kotte’ and is used appropriately when long, circuitous routes are taken.

The Sinhalese were, however, beaten in this battle of wits by the Portuguese firing a gun every hour, which made Cutrim realise the Sinhala subterfuge. His initial success at Kotte was celebrated with volleys of artillery, flag waving and bunting and was followed by another delegation by his colleague Payo de Souza in full-scale pomp on elephants sent by Dharma Parakrama Bahu whose splendour of person and of his court has been recorded by de Queyroz, the famous Portuguese historian.

The treaty resulting from Dom Lourenco’s visit stipulated for 150 bahars of cinnamon in return for the protection of the ports of the ruler of Kotte by the sovereign of Portugal. It was drawn up in Portuguese and Sinhala, the former being retained by the royal council of Kotte and the latter being taken in a sheet of beaten gold to Dom Lourenco who approved it subject to ratification by his father.

The customary Portuguese naval celebration followed while the proverbial Sinhala hospitality inundated the Portuguese flotilla with poultry, plantains, young coconuts, sweet oranges, limes and other fruit and vegetables. The tribute of cinnamon was duly loaded along with two small elephants, one of which was sent by the Viceroy to Lisbon and was perhaps the first to arrive from the East.

Dom Lourenco, whom the stormy waters of the Indian Ocean linked forever with the history of Colombo and the island, died in 1507 in action against the Turks.

(Extracts from the Times of Ceylon Annual 1972)