Sunday Times 2

A nuclear weapons story with a happy ending

View(s):By Shehan Ratnavale

The nuclear debate was at its peak during my university days in the United Kingdom. The Labour Party had endorsed unilateral nuclear disarmament at its 1982 policy conference and even at the constituency level, the debate was in full swing with the acronym for mutually assured destruction (MAD) in regular use. The Labour Party’s successive election defeats led them to abandon this policy in the late eighties.

Analyses on public support for nuclear disarmament seem to suggest it’s somewhat event-driven. The 1962 Cuban missile crisis aroused public anxiety about nuclear war and so too the intensified cold war. More recently the surge of Putin’s tanks and troops into Ukraine had my friends in the UK worried. Some liked their Government’s stance thinking it disastrous to succumb and pacify a ‘megalomaniac bully.’ Others feared the threat of a European nuclear war; they agreed with those that considered Putin a dangerous megalomaniac, but that was precisely why they believed the UK should not antagonise him. Sabre-rattling from the US and like-minded western countries, they believed, was inflammatory and undiplomatic. The nuclear threat they considered real and the lives of their children more important than ‘strategic power plays.’

When Sri Lanka is reeling under an economic crisis, with a full plate of food for all its citizens being a top priority, fears of nuclear war and discussions of disarmament, appear a far-removed academic discourse. But with two nuclear weapons states as neighbours, at least the debate is not so distant. Whatever side of the disarmament debate one prefers, it is interesting to note that there is one country that has developed nuclear weapons and then dismantled them. That is the story of South Africa’s nuclear bombs. The facts are clouded in secrecy and speculation, but what is available has key elements of a Frederick Forsyth novel or Netflix political thriller. Here’s why:

The hidden motive

The villain of the tale is the white minority apartheid Government. In the 1970s, the country was increasingly isolated on account of its racist policies and human rights record. It was also confronted with Soviet-backed liberation struggles at its doorstep in Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Angola and Namibia. As time passed, South Africa became entrenched in a war with Namibia. This war was also closely entwined with the Angolan civil war where South African forces became involved in fighting with well-equipped Cuban and Soviet-backed troops.

Isolated internationally with the US no longer an ally, and with concerns of what it saw as ‘the domino effect’ of Soviet expansionism, the apartheid Government decided to build six ‘Hiroshima-like atom bombs developed at a cost of 400 million dollars. The bombs were each capable of wrecking a large city.

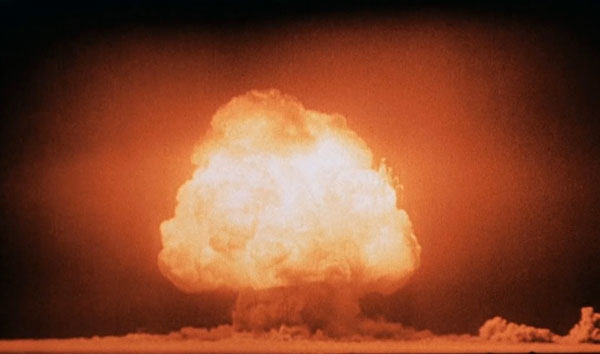

On July 16, 1945 the United States' tested its first detonation of a nuclear device.It was codenamed: Trinity

Given the global abhorrence of apartheid, South Africa did not believe that it would receive assistance if attacked. The bombs were its insurance plan and according to David Albright of the Institute for Science and International Security, the plan consisted of phases. The first was ‘strategic uncertainty’ where the nuclear weapon capability was not acknowledged or denied. If the country was attacked, it would activate phase two of secretly acknowledging the weapons’ existence to western nations. Only if that failed to involve them would they openly conduct a nuclear test and publicly acknowledge the existence of the weapons. The apartheid Government felt that in addition to the test capability, it needed to possess functional nuclear weapons to attract the intervention of western Governments to mediate and de-escalate the conflict.

The covert operators

When Singapore gained independence in 1965, following its cessation from Malaysia, it needed a military and the new government wrote to several countries seeking assistance. Only Israel responded, and befitting the clandestine role often given to them in movies and political thriller fiction, the first batch of Israeli experts sent to Singapore were described as ‘Mexicans’ to disguise their presence.

South Africa’s alleged nuclear weapons cooperation with Israel was much more cloak and dagger and it had to be. Israel followed a policy of ‘deliberate ambiguity’ with respect to its own alleged stockpile of 80 to 400 nuclear warheads and South Africa’s apartheid government was under a 1977 Security Council arms embargo. This resolution also required states to refrain from any cooperation with South Africa to develop nuclear weapons.

It is believed that the international isolation and hostile neighbourhoods experienced by both states enhanced their cooperation. According to the Nuclear Threat Initiative, a US security policy think tank, Israel traded 30 grams of tritium for 50 tons of South African yellow cake uranium. Tritium boosts the explosive power of nuclear weapons.

The Nuclear Threat Initiative also suggests that Israel assisted in the development of South Africa’s RSA-3 and RSA-4 ballistic missiles which are similar to the Israeli Shavit and Jericho missiles. Specifically, on nuclear weapons, foreign press reports suspected that Israel signed a pact with South Africa that included the transfer of military technology and the manufacture of at least six bombs.

The mysterious incident

This is specifically the ‘Vela incident’, sometimes called the ‘Double Flash incident’, and instead of a Frederick Forsyth thriller, it looks more like the espionage techno fiction of the Bond movies. Quite typical of an event that M sends 007 to investigate.

On September 22, 1979, a US Vela Satellite detected a double flash over the Indian Ocean. The event occurred near the remote Prince Edward islands almost equidistant between South Africa and Antarctica. The Vela satellites were developed to monitor compliance with the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty and the double flashes are suspected of having been, but never confirmed to be, a nuclear test. No country accepted responsibility.

If the Vela incident was a nuclear test it is believed that South Africa is the only country in collaboration with Israel that could have carried it out. But investigative panels set up by the Carter administration and the United Nations were inconclusive and leaned towards the view that it was a natural event.

Although theories of meteorites striking the satellite have been speculated, double flashes are a nuclear test characteristic and the previous 41 detected by Vela satellites were all caused by nuclear tests. Evidence also mounts as an earlier South African underground test site in the Kalahari Desert was abandoned after detection. Much later in 1994, Commodore Dieter Gerhardt, a former Commander of South Africa’s Simon’s Town naval base, who was later convicted of spying from the Soviet Union, stated that he had learned that ‘the flash was produced by an Israeli-South African test codenamed Operation Phoenix.

Despite the absence of official confirmation, the fact that this incident is widely seen as a nuclear test is evident from Professor of International Politics at UNISA Jo-Ansie van Wyk making reference to it on South African radio, and saying that ‘we now know it as a joint Israeli-South African test.’

The ending twists in the tale

After having secretly funded, developed and maintained nuclear weapons for over a decade, in 1989 then President F.W de Klerk decided to dismantle them. In 1991 South Africa signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation treaty.

The official explanation given for the disarmament is that heralded by the fall of the Berlin wall, Soviet expansionism was no longer a threat. Some also suggest that since the apartheid Government was at that time negotiating for a transition to democracy, there was a desire to prevent nuclear weapons from falling into the hands of a black majority Government. But President de Klerk has denied this.

After the dismantling, 485 pounds (220kg) of highly enriched weapons-grade uranium has been kept by South Africa at a secure facility. This remained a bone of contention with the US which wanted the enriched uranium converted into reactor fuel. In 2007 there was a serious attack on the facility. The South Africans saw this as common criminality but the US viewed it as something much more sinister.

Notwithstanding this episode, being the only country to develop and then disarm, South Africa is seen as a unique reference point at international fora. With the Ukraine war and the spotlight on North Korea and Iran, the nuclear debate remains topical. As such despite the James Bond-like sequences of its nuclear weapons story, South Africa remains a source of strength for the disarmament lobby and for those nations who in a literal sense wish to assume the role of ‘Dr. No’.

(The writer works for Roelens Solicitors and was a former High Commissioner to the Republics of Singapore and South Africa)