Battle of the Somme and the Trinitians at the frontlines

What remains today: The trenches in France where the 29th Division (among whom were the young soldiers from Ceylon), fought in 1916. Pix by Suren Ratwatte

July 1, 1916, was a bright summer’s day in France. Europe had been gripped for nearly two years in a titanic struggle between the invading armies of the German Empire and the Allies (France, Imperial Russia and Britain). The German offensive of August 1914, which marked the start of the war had been stalled, but at terrible cost. A line of trenches stretching from the North Sea to the Swiss border cut across some of France’s most fertile farmland. The ‘western front’ as it was called, had degenerated into a bloody stalemate. The summer of 1916 was to be the start of a major offensive by the British Army to break the impasse and push back the Germans.

By the end of June 1916, an unceasing barrage of artillery had been devastating the German trenches for a week, or so the Allied Generals hoped. The offensive, scheduled for July 1, was expected to be a ‘walk in the park’ across the German lines, presumed to have been destroyed by shellfire.

This was all a long way from Ceylon, as Sri Lanka was then, a prosperous and peaceful land far from the carnage. But almost a century of British rule had led to many people, particularly in the cities, having a strong ‘British’ identity. So much so that the main English medium schools in the country, Royal College and S. Thomas’ in Colombo, Trinity and Kingswood in Kandy, between them produced 330 volunteers who volunteered to fight for King and Country when the First World War broke out in 1914.

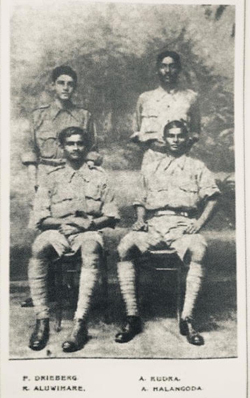

Among these were four boys from Trinity College Kandy – Richard Aluwihare (Senior Prefect of the school and a cricket Lion), Albert Halangode (a rugger Lion), Francis Drieberg and an Indian studying at the school, Ajit (Jick) Rudra.

Richard Aluwihare was my grandfather. He and ‘Uncle’ Jick Rudra remained lifelong friends after the war.

The four Trinitians left Colombo in early 1915, reaching England after a long sea voyage.

After some months, the four finally enlisted in the Universities and Public Schools Brigade (known as the UPS) of the British Army as private soldiers. Their service numbers were: Aluwihare 9289, Rudra 9295, Halangode 9296 and Drieberg 9298. The UPS Brigade consisted of four battalions, three attached to the Royal Fusiliers and one to the Middlesex Regiment. The four friends were attached to the 18th Royal Fusiliers (RF) and finally landed in France in November 1915.

Another Ceylonese, R.H.D. Van Twest was also somewhere nearby. His service number was 9293, which probably meant that he enlisted that same day but we do not know if they ever met.

Another Ceylonese, R.H.D. Van Twest was also somewhere nearby. His service number was 9293, which probably meant that he enlisted that same day but we do not know if they ever met.

In the trenches

The 18th RF saw action at the tail-end of the Battle of Mons, being transported to the front in ‘double-decker buses’ recalls Rudra in his autobiography . From there, they were sent to Ypres and did their first stint in the trenches, which Rudra remembers as being “…exposed to rain and sleet, which were frequent that winter.” Going from the balmy climes of Kandy to winter in a hole in the ground in the midst of the carnage, must have sorely tested the lads.

The UPS battalions engaged in deadly trench warfare for many months at the front. Barbed wire had been introduced by then, the opposing armies separated by ‘no man’s land’ — 300 yards of hell, an area churned up by shelling, full of corpses and rats ‘as big as cats’ my grandfather recalled in one of the few times he ever talked about the war.

Finally, they were withdrawn from the front line to Northern France for rest and recuperation. The relief must have been short-lived. The UPS battalion was disbanded on March 21 as recorded in my grandfather’s war diary, which I have with me as I write. The original promise was that the young men who were Privates (the lowest rank) in the UPS would be made officers after seeing ‘action’. But this was deemed to be for British (read white) soldiers only – no Asians would be considered.

The four Ceylonese attached to the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers as Privates still, were sent to the Somme in May 1916. Huddled in one of those muddy trenches on July 1, 1916, they were part of the 29 Division, which was poised to go ‘over the top’ that fateful morning at the start of the Battle of the Somme.

Probably unknown to them, another young man from Ceylon, Peter Robert de Silva was with the Middlesex Regiment in a nearby trench. De Silva, who had also joined the UPS (his service number was 3198 so he must have joined earlier), had already been deployed to France with his regiment. Van Twest was also not far away, by then a Sergeant in charge of a machine gun platoon.

The big ‘push’

Well preserved: The German trenches

The Somme offensive, which began on July 1, 1916, was the largest battle initiated by the British Army in the war.

Leading up to the battle, my grandfather’s diary laconically states “bombardment”. The British actually fired an estimated 1.5 million shells over a week, which were expected to destroy the barbed wire and kill or disable the German soldiers in their trenches.

So confident were the Generals of victory that the soldiers were ordered to march across ‘no man ’s land’ in formation and take over the enemy trenches.

A bloody cost

The reality was very different. Rudra remembers “As soon as we had scrambled up and began our charge, we began to be mowed down by enemy machine guns.” Rather than being killed, the Germans had been sheltering in deep bunkers and were able to man their weapons to maul the advance.

“The troops ahead of us were being cut down almost to a man,” recalls Rudra. “Then we saw an extraordinary sight. A Highland (Scots) Regiment in their kilts and plaids advancing line by line perfectly dressed, their pipers playing them on. They marched resolutely to their deaths in drill formation.” Only one sergeant and eleven men of that Scots battalion were to survive the attack.

Rudra and Aluwihare were advancing from crater to crater, trying to stay out of the carnage when a shell landed close by. “We were all lifted out and flung,” writes Rudra. “I saw Richard lying in the open, his uniform covered in blood. We dragged him into a crater, patched him up as best as we could and waited for darkness to fall. Being midsummer, it must have been nine or ten o’clock before we were able to drag Richard back with us. We finally made it back to our line about three in the morning.”

Aluwihare’s diary merely records, “Wounded at 11am.” Their friend Frank Drieberg was not so lucky – he was killed that morning. Van Twest received a gunshot wound to his head, but survived. Peter de Silva was initially reported as ‘missing in action’ that day, along with thousands of others. Finally, his grieving family in Ceylon was informed in April 1917 that he had been killed in action. We can only assume that his body had been recovered and identified. De Silva’s grave lies in the Hawthorn Ridge Cemetery No. 1, alongside 152 other graves of young men killed that day.

The Hawthorne Ridge Cemetery No. 2, which is nearby, has another 214 graves. One of which simply states Private F. R. Drieberg, Royal Fusiliers, 1st July 1916. Age 19.

Young lives lost: Private F.R. Drieberg's grave at Hawthorn Ridge Cemetery No 2 and (right), the grave of another Ceylonese Private P.R. de Silva at Hawthorn Ridge Cemetery No 1.

The inscription surmounts a crown and a poppy, the flower which bloomed all over the killing fields and became a symbol for the thousands of young men so needlessly killed. The words ‘Honi soit qui mal y pense’ are inscribed around the poppy – medieval English for ‘Shamed be whoever thinks bad of it’. Over 20,000 other young men are buried in the cemeteries nearby.

The British offensive was a colossal failure with almost no ground being gained that day but with a butcher’s bill of unimaginable proportions. The British would suffer 57,470 casualties including 19,240 deaths on July 1 alone, the highest death toll in one day in the long history of the British Army.

Post the Somme

Aluwihare and Halangode, seriously wounded, did not see any fighting for the remainder of the Great War. Rudra, miraculously untouched, returned to the front line until he was wounded at Cambrai a year later.

Finally selected to be an officer, the war ended before Rudra finished his training. He recalls the huge spontaneous party that took place in London as the Armistice was announced on November 11, 1918. “A uniform was the passport to all amenities. We paid for nothing and were hugged and kissed by numerous girls. Joyous crowds gathered at Piccadilly Circus celebrating the end of a long, terrible war.”

They were not to know that the unjust and vindictive terms imposed on Germany would only lead to bitterness and, in just 21 years’ time, a second war would erupt. This one a truly global conflict that would engulf the little island of Ceylon as well.

Return home

On his eventual return home Rudra decided to become a professional soldier, joining the Indian Army and making it through another World War where he served on the General Staff of the Indian Army. During the chaos that followed the partition of India, Rudra continued to play a crucial role, before finishing his career as a Major General and living to the ripe old age of 97. He passed away on November 3, 1993 in Delhi.

Richard Aluwihare also returned to Ceylon and joined the Ceylon Civil Service, reaching the rank of Officer Class One. He was Government Agent for the North Central Province and the first Ceylonese Inspector General of Police. Knighted in 1948 to become Sir Richard KCMG, CEB, he also served as Ceylon’s High Commissioner to India from 1957 to 1963, where he rekindled his friendship with his schoolmate Jick Rudra. Sir Richard passed away on December 22, 1976.

Of Albert Halangode’s life after the Great War we know little. His nephew John Halangode had a long and distinguished career in the Ceylon Army retiring as a Brigadier-General. His son Hiran followed the family tradition also attaining the rank of Brigadier-General, the third generation to serve their country.

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.