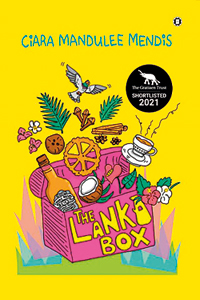

Unpacking The Lanka Box

View(s):A volume of short fiction is exciting because it allows both reader and writer to rummage through an assortment of themes, ideas and images without the need to stitch or to unravel a single totalizing grand narrative that holds everything together. This is particularly valuable in the context of South Asia where jagged territorial and regional pressures play out against an inheritance of common political and cultural concerns. Indeed, the distinguishing feature of The Lanka Box is the way in which it unerringly identifies and explores issues that cut across national boundaries in the region, and thus proves to be of value to a broad range of readers.

To begin with, The Lanka Box tackles a broad range of issues around the question of the choice of a national language on a subcontinent that continues to feel the need to demonstrate decolonisation through its articulation of a language policy. The lead story, ‘Of Concepts, Coconuts, and the Blood of Christ,’ indicates the black ironies consequent on the choice of a single-language policy. Government officials can of course only own to knowing the national language. However, English — the language of the coloniser — remains the weapon of choice on formal occasions.

To begin with, The Lanka Box tackles a broad range of issues around the question of the choice of a national language on a subcontinent that continues to feel the need to demonstrate decolonisation through its articulation of a language policy. The lead story, ‘Of Concepts, Coconuts, and the Blood of Christ,’ indicates the black ironies consequent on the choice of a single-language policy. Government officials can of course only own to knowing the national language. However, English — the language of the coloniser — remains the weapon of choice on formal occasions.

Therefore, they hire a speech-writer from a missionary school, a little ‘Rome in Colombo,’ and are content to have him serve as ventriloquist, in a manner of speaking, on behalf of the constitution and the republic. A later story reminds the reader how painful the alliance between language and class can seem to those who have no access to opportunity to learn in any medium other than their mother-tongue. Speaking of the protagonist of the story, ‘Hibiscus Miss,’ a character reminisces about the way in which she would not speak to anyone who did not know English. ‘Even broken English is better than no English. My God, is that the way to pick your people?’

On the national level, a rigid language-policy gives rise to pantomime that masquerades as governance, and on the human level it keeps people apart. This is a situation to which readers from all former colonies in South Asia can relate. On the one hand, emergent governments use the moment of independence — fondly called decolonisation — as a chance to assert the dominance of one language-group over others. On the other, linguistic chauvinism ensures that a new set of rulers merely replaces the old. The surest way to combat neo-colonialism is to empower as many languages as possible to develop.

Languages in turn, bring clashing value-systems in their wake and as happens very often, the poor, the young and the most vulnerable pay difficult and unaffordable prices. Sara Suleri’s Meatless Days (1989) dramatises the ways in which gender and class complicate language-choices in South Asia. Mendis thinks this issue through in The Lanka Box by introducing income and age as further variables in this situation.

Another theme involves the way in which emergent nations find that the evolution of a national identity is a slow and painful process. ‘The Bringer of Happiness’ reminds readers that traditional dress may serve as a marker of religious and ethnic identity in a way that can be troubling. When two young women — both training for government service — discuss this, the conversation may seem fatuous. ‘”Is it easy? Wearing the saree?” “Not as easy as wearing the abaya.”’ Beneath this light exchange however runs the reminder that the abaya signals a specific religious and ethnic affiliation. Its wearer, Sarah is a Muslim of Tamil origin, to whom Sinhala as a language is again, a closed option. As soon as the Easter bombings of April 2019 take place, she becomes the target of security-searchers, and many of her course-mates pull away. So does Sarah. Again, personal and political identities seem inseparable from ethnic origin. Citizenship takes a long time to evolve, and as we watch the way in which professional and personal affiliations push Sarah and the protagonist now in one direction, and now in another, we learn a home truth that is applicable across all emergent nation-states in South Asia. Governmental pressures, whether colonial or neo-colonial, play havoc with personal relationships and with loyalties that cut across religious and regional boundaries. How does governance need to evolve to work differently in an emerging nation-state, and what are the lessons that those who govern need to discuss and resolve? From where does one seek inspiration for a new collective mind-set?

This becomes painfully evident when academia and administration collide over the preservation of one’s national heritage. As a newly-appointed minister snaps, ‘All right then, don’t give me something huge like Finance or Health, just give me something light which nobody really cares about, like Culture.’ He cannot imagine why curators and teachers should find it in the least difficult to free space by cramming over 50 paintings together, so that they use just ‘One Wall for Everything,’ in the story of the same name. Under such circumstances, how can literature speak truth to power?

The great strength of The Lanka Box is that it impels the reader to ask such a question. It may not always attempt to respond, because, as ‘The Canada Wife,’ shows, fiction in particular and literature in general are also tired and unsure of their ability to negotiate the violence and bruising of history. This diffidence may disappoint, but is also realistic. Where The Lanka Box disappoints unnecessarily is perhaps in its unwillingness to respect its own capacity to disturb things. It asks the tough questions but perhaps should stand without shuffling its feet while it seeks to answer them.

(The reviewer is Professor, Department of English, University of Delhi)

| The Lanka Box- by Ciara Mandulee Mendis Reviewed by Christel R. Devadawson | |

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.