A fitting memorial

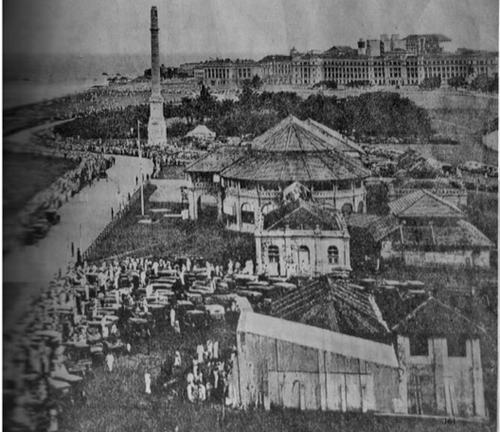

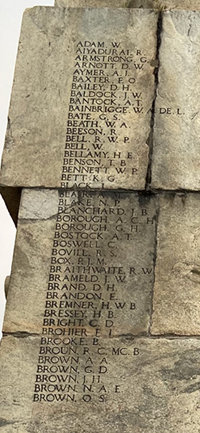

The War Cenotaph: Now at Viharamahadevi Park and (bottom right), a section of the names engraved. Pix courtesy Quintus Andrade

In 1923 Ceylon was a different place to the Sri Lanka of today. The land was ruled by the Empire’s masters, ensconced in their ‘Britishers Only’ Colombo Club near Galle Face Green. The Ceylonese had, however, formed their own rival Orient Club located near the racecourse.

‘Divide and Rule’ was the unwritten law. ‘Natives’ were not permitted to play in the Colombo Club’s cricket and rugby teams. Instead, they congregated in the Singhalese Sports Club, Tamil Union, Burgher Recreation Club, Moors Sports Club, Colombo Malay Cricket Club, etc, also constituted along ethno-religious lines.

But just next to the exclusive Colombo Club, a memorial designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens (the famous architect who masterminded New Delhi) was being built. The Victory Tower as it was originally known (later renamed Colombo Cenotaph) was unveiled on October 27, 1923, by the Governor Sir William Manning, a former Brigadier General who had seen action in Burma, India and Africa.

On it were carved the names of 450 young men (and one woman) who gave their lives in the Great War (World War 1), in defence of the Empire. Here, though, there was no discrimination. Names on the monument were engraved in strict alphabetical order, beginning with Adam and Aiyadurai, continuing through the likes of Brown, De Alwis, Drieberg, Jacotine, Krause and Obeysekera, to others such as Paramanathan, Perera, Samarawickreme, Speldewinde, Wijekoon and Zinovieff.

Neither race, religion, nor ethnicity is mentioned. It is a stark and fitting tribute to young Ceylonese who made the ultimate sacrifice in the defence of what they saw as ‘their’ country.

The Cenotaph soon became a prominent landmark. The cream of British society ‘took the air’ of an evening on Galle Face Green near the Colombo Club premises, enjoying the cool sea breeze.

Just across the mouth of the adjacent Beira Lake stood the Echelon Barracks, the base of the Ceylon Defence Force (CDF). As Ceylon had no need for a professional army, the CDF was largely a volunteer group mostly comprising part-time soldiers.

The Ceylon Light Infantry (CLI), one of the few ‘regular’ units of the CDF, was retained in Ceylon during the war. Many members of the Ceylon Mounted Rifles, predominantly British residents working in large firms with offices in the city, immediately volunteered for service when war was declared in August 1914. So did many of the Ceylon Planters’ Rifle Corps (CPRC) based in Kandy, primarily composed of tea and rubber planters.

Those with previous military experience were sent to regular units of the Indian Army as officers. Others were attached to the ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) division for training in Egypt. Many individuals were selected for officer training at this stage too, but a small group remained. They provided a bodyguard to Lt. General William Birdwood, commander of the abortive invasion of Turkey at Gallipoli. Several of the names on the Cenotaph are from the ranks of the CPRC.

The reaction and response among British residents of Ceylon was understandable. But, there was an also an upswell of patriotism among the Ceylonese, particularly those who lived in Colombo and Kandy. This is reflected in the diversity of names immortalized on the Cenotaph.

Standing tall at Galle Face: The Victory Tower as it was then known

Richard Aiyadurai’s is the second name on the first panel of the Cenotaph. A young man who was educated at Trinity College, his address is given as Vadukoddai, Jaffna. A Lance Corporal with the Royal Fusiliers, Aiyadurai was 27 years old when killed by a sniper in December 1917. He has no known grave but is honoured at the Cambrai Memorial in France.

Frank Drieberg was another Trinitian who volunteered, along with my grandfather Richard Aluwihare and a group of their friends. Drieberg made the ultimate sacrifice on July 1, 1917, the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Peter De Silva died on the same day; they are both on the third panel of the Cenotaph. Their graves are on Hawthorn Ridge in France, where they fell.

Aiyadurai was one of a party of 45 in Colombo who in 1915 boarded the Ville de la Ciotat, a cruise liner of the French Messageries Maritimes merchant shipping company, bound for France. Whether all members this group were intent on joining the British Army is unknown, but the ship’s manifest lists them as ‘volontaires anglo-cinglais’ (Anglo-Ceylonese Volunteers) so we can assume this was the case.

The ship was torpedoed by the German U-boat (submarine) U-34 Claus Rücker on December 24, 1915, in the Mediterranean Sea. The stricken vessel sank rapidly with 35 passengers and 46 crew losing their lives. Sadly, a number of those on the Cenotaph were among this group, including C.H.S. De Saram, C.W. De Vos, W. Neville, A.F. Obeysekera, S.O.L. Pereira, A.G.F. Perera, W.E. Speldewinde and G.P. Stirling.

C. L. Mellonius, S. Ramanathan and R. Jacotine were on the same ship and survived the sinking, only to be later killed in battle.

No doubt all of those immortalized on the Cenotaph were courageous individuals. One recognized as being particularly heroic is Basil Horsfall, who was born in Ceylon and educated at S. Thomas’ College, Mt. Lavinia. Horsfall was awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest award for bravery in the British Empire, for his courage under fire in March 1918. Missing in action (MIA), he too has no known grave, but is honoured both on the Colombo Cenotaph and the Arras Memorial in France.

A handful of Ceylonese joined the Coldstream Guards, the oldest and one of the most prestigious regiments in the British Army, among them C.H. Kale, R. Jacotine and M.D. Jansz. Kale is particularly interesting as he was a veterinary surgeon from Galle who served with the Army Veterinary Corps in Gallipoli before joining the Coldstream Guards in 1917. Kale and Jansz died of their wounds in hospital in the UK in 1918. They are buried in that country. Harold and Eric Jacotine, brothers from Kandy, both served in the Coldstream Guards. Harold was MIA in April 1918 and has no known grave. He is honoured on the Ploegsteert Memorial in Belgium as well as the Cenotaph. Eric survived the war, married an Englishwoman, fathered five children and lived in Shropshire until his death in 1957.

The only woman memorialized on the Colombo Cenotaph is Lillian Midwood, a nurse who is buried in the Alexandria War Cemetery in Egypt. Her brother Harry, a planter in Ceylon before the war, also served but survived.

The Ceylon Sanitary Corps was a unit of volunteers attached to the Royal Army Medical Corps. They saw service in Mesopotamia (now Iraq) providing support for the campaign against the Ottoman Turkish forces. H.C. Wijekoon, S. Poulier and H. De Vos were members of the CSC who gave their lives. The first two are buried in the Baghdad Gate cemetery; De Vos lies in Basra, Iraq.

As can be seen from the few names mentioned above, a significant cross-section of Ceylonese society was represented among those who volunteered to fight for the Empire.

Sadly, the peace that was imposed on the defeated German people proved to be an unjust one, and all too soon, war clouds were gathering. In less than 20 years since the Cenotaph was unveiled, Britain was once again at war. Not only with Germany in Europe but also with Japan in Asia, where the Imperial Japanese Navy threatened Ceylon.

The Cenotaph, visible for miles out to sea, was deemed an ideal marker for artillery purposes, potentially enabling the enemy to shell the Colombo Fort and environs from offshore. Fearing such a threat, the Cenotaph was dismantled and re-erected in its present location, safely inland, surrounded by trees in Victoria Park (now Viharamadevi Park).

The Cenotaph, visible for miles out to sea, was deemed an ideal marker for artillery purposes, potentially enabling the enemy to shell the Colombo Fort and environs from offshore. Fearing such a threat, the Cenotaph was dismantled and re-erected in its present location, safely inland, surrounded by trees in Victoria Park (now Viharamadevi Park).

As it turned out the Japanese fleet did attack Ceylon in 1942, but it was an aerial raid by carrier-borne aircraft. Although a brief and small part of a globe-spanning conflict in what became known as the Second World War, Sir Winston Churchill later declared Japan’s thwarted assault on Ceylon as the war’s “most dangerous moment”.

The Cenotaph was built to honour those who gave their lives in the ‘war to end all wars’. But that proved to be an optimistic label.

The Second World War ended in 1945 with a death toll far exceeding that of the Great War. A number of Ceylonese who sacrificed their lives in WW2 are also remembered on the Memorial Wall located near the Colombo Cenotaph.

Bitter lessons learned in 1918 were applied and more just terms imposed on the vanquished. This has resulted in a ‘long peace’ in western Europe, lasting more than 75 years.

As we celebrate 14 years since the guns were silenced in Sri Lanka’s ‘long war’, it would do us well to remember the words of Siddhartha Gautama (Lord Buddha):

Na hi verena verani

sammanti’dha kudacanam

Averena ca sammanti

esa dhammo sanantano

(Hatreds never cease through hatred. Through love alone they cease. This is an eternal law.)

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.