Sunday Times 2

Memories of that Black September

View(s):By Shehan Ratnavale

My father had taken up his appointment as Sri Lanka’s envoy to West Germany in June 1972 and the Munich Olympics began on August 26. Taking place only 27 years after the end of World War II, German policymakers intended the games to be a global ‘coming out party’, heralding a new chapter for the country.

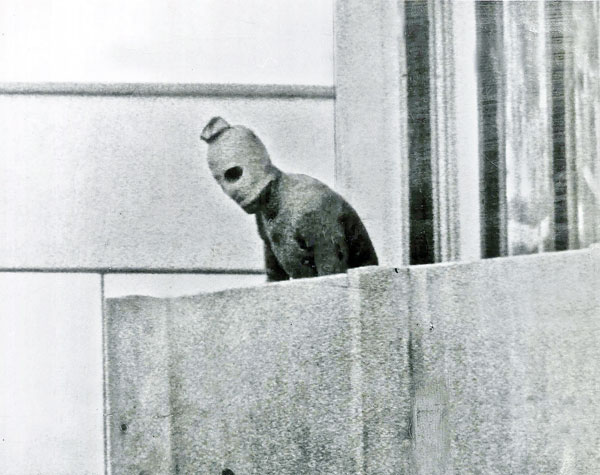

The famous photograph of the Black September terrorist on the balcony of the Israeli team apartment

The atmosphere was of a cosmopolitan carnival. I recollect two well-spoken young women uniformed in mauve sarees doing an excellent job for our tea board. They persuaded many to sample the excellence of our tea but complained that their Indian counterparts could wear sarees of their choice. I also recall accompanying my parents to visit the Sri Lankan team in their Olympic Village apartment. SLB Rosa was Sri Lanka’s main hope for a medal having won gold at the 5000 and 10,000 metres at the 1970 Asian Games. The team was enthusiastic and hopeful and I was told off by my mother for bringing up the baila lyrics ‘Rosa polla geneng balla maranna.’ Thankfully Rosa was a friendly man who enjoyed the humour. Unfortunately, he didn’t quite perform up to expectations.

Understanding the context is crucial to understanding what happened. This was the Germany of the seventies, and from the numerous Mercedes trucks on an impeccably maintained network of autobahns, it was evident that the country was pounding with industry and unquestionably an economic miracle. But behind this success, the collective guilt and stigma of the war lingered. While German efficiency was admired, German militarism had become something of a joke with British sitcoms from ‘Dad’s Army’ to ‘Fawlty Towers’ taking regular swipes. I recall my father remarking on the ‘Deutsche Hitparade’, the German equivalent of ‘top of the pops’ that even their pop music clapped to a martial beat.

For the Munich Olympics organisers, a more poignant reminder of German militarism was the1936 Berlin Olympics. That was Hitler’s fascist fantasy intended to showcase Germanic racial superiority, anti-Semitism and where soldiers marched and saluted Hitler. It was a compelling reason to discard the imagery of the past so the Munich organisers minimised security. This was to showcase a country that was now modern, vibrant, open and inclusive. But they seem to have taken it much too far!

At 4:30 a.m. on September 5, 1972, the Black September faction of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation attacked part of that same Olympic village where we earlier visited the Sri Lankan team. But their target was the apartments of the Israeli team. Unhindered by the lax security, eight of them dressed in tracksuits carrying duffel bags containing weapons, scaled a 2-metre fence to enter the compound. They had even received assistance to scale the fence from unsuspecting foreign athletes who happened to be sneaking back into the Olympic Village in the night.

Once inside, the attackers forced their way into the Israeli apartments. They captured nine hostages and their demands were that 234 Palestinians held in Israeli jails be released.

Israel’s response was that there would be no negotiation with terrorists as they believed this would incentivise future attacks. The German Government offered the terrorists an unlimited amount of money but this was rejected with the reply: ‘Money means nothing to us. Our lives mean nothing to us.’

Eight hundred million TV viewers established this as the first terrorist attack in the full public glare, but live TV was even watched by the terrorists. These images wrecked an attempted rescue and warned them that their demands would not be met. A final botched rescue attempt took place at an airport after the terrorists had negotiated passage to an Arab country with the hostages. A fire fight that took off with German snipers ended up with the terrorist throwing a grenade into a helicopter carrying the hostages and shooting the remaining hostages in another copter. All the Israeli hostages were killed. Five of the eight terrorists were also killed.

There was condemnation and horror as at one stage it was believed that the rescue had been a success. At a tearful memorial service for the slain Israelis, the President of the International Olympic Committee announced that they ‘cannot allow a handful of terrorists to destroy this nucleus of international cooperation and goodwill’ and the games will continue. The flags of most nations flew at half-mast but the Middle East was a tinderbox at that time and 10 Arab nations declined to do so.

The irony of Jews being massacred in Germany was not lost on the world. The famous Jewish American swimmer Mark Spitz collected his record 7 gold medals at these games but fearing for his life left immediately after his events. With accusations of not acting on prior intelligence, poor coordination, and incapacity, the German handling of the situation came in for severe criticism. The German constitution prevented the army from being used inside Germany in peacetime and as a direct consequence of this attack, a special police counter-terrorism unit GSG 9 was set up. It was five years later that this unit’s handling of the Lufthansa hijacking at Mogadishu regained Germany’s reputation for tactical efficiency.

Although the Palestinian attackers failed in their objective, supporters believed they had captured the global spotlight. People now knew about their cause which hitherto received scant media attention. A hijacking soon after managed to obtain the release of the three surviving terrorists but Israel had no intentions of letting the perpetrators or the planners off the hook.

As a response, Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir activated the ‘operation wrath of God’ sending a Mossad team to assassinate those responsible. But in addition to being ‘sweet’, revenge is often messy and while many responsible were killed, in what became known as the ‘Lillehammer affair’ they also mistakenly killed an innocent Moroccan man unrelated to the attack.

While the movie ‘21 Hours at Munich’ and the documentary ‘One Day in September’ cover the Olympic attack, Steven Spielberg’s movie ‘Munich’ addresses the Israeli response. The film is intense and bloody as it seeks to capture the reality of the circumstances. The film is also objective and its dialogue does justice to the differing conflict perspectives. In Spielberg’s portrayal, as the Mossad team reflect on the cost and consequences of their assassinations, one says: “Mrs. Meir says to the Knesset ‘the world must see that killing Jews will from now on be an expensive proposition’ but killing Palestinians is not exactly cheap.”

Fifty-one years later the conflict and sadly the atrocities continue. Taking a cue from the movie dialogue we can only pray that more is done by the international community using whatever mechanisms available to ensure that killing both Jews and Palestinians becomes a prohibitively ‘expensive proposition.’

(The writer works for Roelens Solicitors and was a former High Commissioner to the Republics of Singapore and South Africa)