News

Alarming literacy and numeracy skills deficit in primary children

View(s):By Tharushi Weerasinghe

A survey by the Education Ministry has found that an alarming percentage of primary schoolchildren lacked basic literacy and numeracy skills.

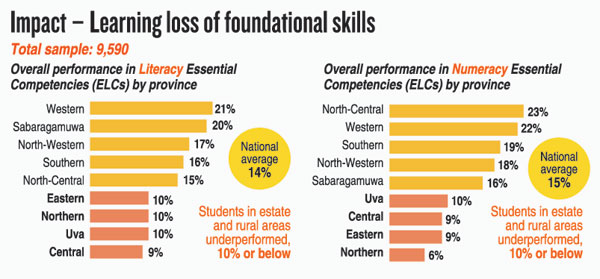

A Learning Crisis and Recovery Study that assessed the foundational skills of Grade 3 students found that only 14% and 15% of Grade 3 students achieved all the foundational skills under ‘Essential Learning Competencies’ in literacy and numeracy respectively, in 2021-2022.

Prolonged school closures are believed to have had an impact.

“My son was 4 and enrolled in preschool when Covid-19 hit, and he is 7 years old and struggling to keep up with the work in Grade 2 now,” noted Sarmili Thurairetnam, a non-governmental humanitarian sector worker based in Kilinochchi. In families like Sarmili’s where economic conditions compel both parents to work, it had been impossible to give their child the close academic attention and socio-economic learning they would have received in school.

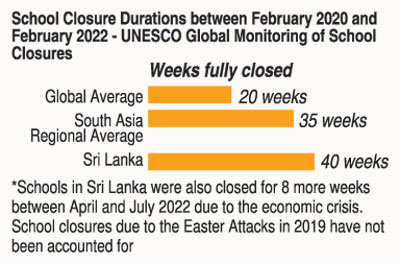

According to the UNESCO Global Monitoring of School Closures, Sri Lanka experienced 40 weeks, one of the longest full closures in the world, of school closures during COVID-19 epidemic between February 2020 and February 2022. Beyond this, Sri Lanka experienced an additional eight weeks of school closures due to the economic crisis between April and July 2022. These statistics have not taken school closures due to the 2019 Easter Sunday bombings into consideration.

“My husband and I would carve time out to spend with him, but this was very difficult even when we were working from home,” she said, adding that this means her son often spent a lot of time watching television when there was no one to play with him. Now in grade 2, he is among 20 other students in a class of 30 that is struggling to write basic letters.

Thirty one per cent of parents did not believe that their child’s school has taken adequate steps to make up for learning loss and another 13% did not know, based on UNICEF’s 7th Round Telephone Survey between October and November 2022.

“A small number of the children are keeping up well but these were students that had access to online classes during school closures, most families here can’t afford that kind of tuition.”

The MoE calculates that a total of 4.8 million children and adolescents across the country were affected by the pandemic and the economic crisis due to high costs of educational materials, fuel shortages and transport costs, disruption to social services, and the deprivation of nutrition.

Impacts have been felt in varying degrees across families in various income brackets, but the most socioeconomically challenged have been hit the hardest.

Rupina Ranasinghe is a mother of three children in pre-school and primary school from a small agricultural village in Dambulla. In these already economically challenged areas, successive crises have completely crumbled children’s education. When fuel shortages hit the country they could no longer take the children to the schools or their produce to the market, and when fuel finally arrived they couldn’t afford it. Even now the impacts are poignant – they live on one meal a day.

Rupina does not have a smartphone so online education was not accessible at all. “My oldest daughter didn’t have two years of primary school because of the disruption,” she said.

On average, only 34% of primary students between Grades 1-5 were able to access distance learning during these school closures, with lower proportions of socioeconomically disadvantaged children from rural and estate areas having access. Only 26% of Grade 3 students were able to access distance learning.

The Grade 3 study being the first of its kind, there is no comparable ‘before’ and ‘after’ data to evaluate whether the worrying statistics are the result of school closures alone, but experts claim that they merely exacerbated systemic issues that had already existed for decades.

“If we gave these children past papers of some sort they would’ve got much better results but since the study applied what I would call authentic assessments, we were able to see a more realistic picture of where students stand in terms of skills,” noted Dr. Sujata Gamage, senior fellow at LIRNEasia.

She coined the term “pseudo assessment” for the type of testing in Sri Lanka where children are educated for the sake of answering specific questions at examinations as opposed to meaningful skill development. She noted that there has been evidence, previously, to prove the fact that the education system of Sri Lanka was “teaching to test” and not to assess whether the child has understood a concept.

“COVID-19 alone could not have done this much damage,” agreed Prof. Gunapala Nanayakkkara, senior adviser to the MoE.

According to Prof. Nanayakkara, the lack of continued attention to teacher training, resource allocation, and supervision were major causes. “In fact, there is no school supervision happening at all at the moment,” he noted. He concurred with Dr. Gamage’s sentiments as he noted that the Grade 5 scholarship examination was proving to be a massive obstacle in the provision of effective skills training to primary school children as primary education was solely focused on getting students to answer the question paper well.

While noting that overnight change cannot be found for conditions that have prevailed in the education infrastructure for decades, the professor noted that work will be done through the upcoming budget to allocate criteria-based, specific capital and recurrent budgets, to cover ongoing expenses, to all the schools.

A cluster system will potentially be introduced to facilitate this. Schools will be clustered around a leading school and 1,220 clusters will be formed and then grouped under 510 school boards. Every school board will supervise about three school clusters with a team of education experts and centres for coordinating plans and resource sharing for each cluster. This recommendation was, according to the professor, given by an expert committee appointed by the Cabinet and the mechanisms to activate are ready for implementation following Cabinet approval.

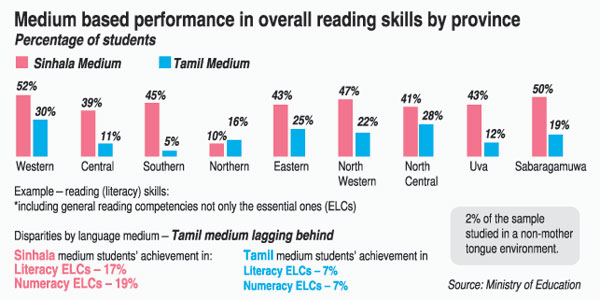

The study also showed that learning disparities were even more divided when compared between language mediums. Seventeen per cent and 19% of Sinhala medium students achieved their ELCs in literacy and numeracy respectively while only 7% of Tamil medium students achieved their ELCs in both.

“The lack of Tamil-speaking teachers is a problem,” admitted Prof. Nanayakkara who added that a paper prepared by the ministry has gone through to the National Institute of Education for a policy on bilingual education whereby more teachers will be recruited and trained on bilingual teaching practices.

The MoE has also been instructed to submit a report with feasible alternatives and solutions for the next two years, by the end of this month. The solutions being explored include the extension of learning hours, speedy recovery assessment and feedback methods, and the use of more learning resources with supporting equipment in classrooms.

“The role of parents is also being enhanced in the approach we are planning on taking.” This report will be presented to foreign donor agencies, 10 of which have come forward to provide monetary support and human resource training activities.

Some efforts have already begun. Led by the MoE and in close coordination with the provincial education authorities, UNICEF has been supporting the national learning recovery efforts through remedial programmes in all nine provinces to provide extended, targeted assistance to support primary children, especially the most disadvantaged, with literacy and numeracy learning. So far UNICEF’s learning recovery assistance has reached more than 391,000 primary students.

“Immediate and urgent actions are needed to address lost learning for the country’s 1.6 million primary schoolchildren impacted by long-term school closures and sudden disruptions due to COVID-19 and the economic crisis,” noted Takaho Fukami, UNICEF chief of education.

UNICEF has also been a key partner to the MoE in addressing the challenges, including through the provision of education materials (benefiting 274,000 disadvantaged students), preschool meal programmes (covering 49,000 preschool children), and psychosocial support to 20,000 secondary students.

A total of Rs. 26 million has been requested by the MoE from the Government, to combat the Grade 3 learning crisis that the report has revealed, Secretary to the Ministry Nihal Ranasinghe told the Sunday Times. Information on how this sum will be allocated was not available with the secretary at the time of press.

The best way to say that you found the home of your dreams is by finding it on Hitad.lk. We have listings for apartments for sale or rent in Sri Lanka, no matter what locale you're looking for! Whether you live in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Matara, Jaffna and more - we've got them all!