How Ceylon came alive in Dickens’ writings

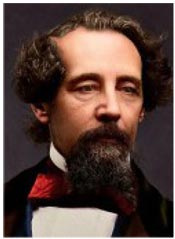

Charles Dickens

An anthology by Charles Dickens entitled ‘Sunshine on Daily Paths’(or the ‘Revelation of Beauty and Wonder in Common Things’,1 picked up in an antiquarian bookshop in the UK, included six of its 45 chapters on different aspects of life in Ceylon, all written in the first person.

I asked myself the question: Did Dickens really visit Ceylon? If he did, why is there no record of the visit of such a famous person in our 19th century history? Could he have visited Ceylon incognito? If he did not visit, how did he write so accurately, and in such detail, about the places visited?

I decided to investigate these questions.

Life of Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (popularly known as Boz) has been acclaimed as one of the most prolific English writers of the 19th century, and often described as the William Shakespeare of the 18th century. Dickens started his writing career contributing to periodicals. Having first served as editor of a weekly magazine, Bentley’s Miscellany, he established his own weekly periodicals, Household Words (from 1850 to 1859), All the Year Round (from 1859 to 1870) – popular outlets for some 390 writers over nine years. Dickens was a prodigious contributor himself on a wide variety of topics, serializing most of his books before publishing them as books.

Dickens’ life is a real “rags to riches” story. He was born in Portsmouth on 7 February 1812 to John and Elizabeth as one of ten siblings. Having lived in Chatham in Kent, the family moved to London in 1822 and settled in Camden Town. After John was imprisoned for debt, the impoverished family took Charles out of school and sent him to work at a factory in Charing Cross, where his job was to paste labels on bottles of shoe polish. Many of the characters associated with his earlier life, such as his schoolteacher, his landlady and the other children he worked with, feature in his novels. It also created in him an empathy for the down-trodden of society.

Although his father subsequently came into an inheritance and was released from prison on paying his debt, Charles continued to work in the factory until he had a disagreement with its owner. He was then sent to Wellington House Academy in North London, where he had an education from 1825 to 1827.

When the family was evicted from their home in North London in 1827, Charles at 15 gained employment as a solicitor’s clerk at Ellis & Blackmore, Gray’s Inn. During his brief time with the law firm, he learnt shorthand rather than law, and from 1828 to 1829 worked first as a freelance reporter and then as a parliamentary reporter.

In 1833, Dickens published his first story, A Dinner at Poplar Walk, in The Monthly Magazine. A year later, while working as a correspondent for The Morning Chronicle, he met Catherine Hogarth, a fellow-worker, whom he married two years later. In 1836 he resigned from The Morning Chronicle, and started editorship of a magazine, Bentley’s Miscellany.

In 1837 the first of his ten children were born. That same year Dickens moved to 48 Doughty Street, London, now the Dickens Museum. In 1839, in search of more space, the family moved to Devonshire Terrace near Regents Park, where they lived until 1851. After two tours to the Continent, the family moved again to a section of Tavistock House in Bloomsbury, London, at the site now occupied by the British Medical Association. Dickens lived there until 1861, when he bought a house named Gads Hill Place in Rochester, Kent. By now, he was an elite member of London’s high society.

In 1858 he separated from his wife, Catherine. Opinion is divided as to the reason for this separation. Dickens alleged she was mentally deranged and was unable to care for the family. Some attribute the separation to Charles’ infatuation with a young actress named Ellen Ternan, which he vehemently denied in a statement (now known as the Violated Letter) given to his manager, Arthur Smith, and unwittingly published first in the New York Tribune and later throughout England. Charles’ explanation of the separation is similar to the storyline in one of his novels, Dombey and Son, which was written during a trip to the Continent.

Charles was now living in Gads Hill Place with the rest of his family except his eldest son, who lived with his mother. He liked living there and was quite productive, completing A Tale of Two Cities and writing Great Expectations and Our Mutual Friend, the first volume of which was dedicated to his friend, Sir James Emerson Tennent, Colonial Secretary of the Ceylon Government from 1845 to 1850.

On his return from a brief visit to Paris in 1865, Dickens was involved in a train accident at Staplehurst on the boat-train. He helped in the rescue work following the accident and retrieved his manuscript of Dombey and Son. While only slightly affected physically, the incident affected him psychologically, and he developed a fear and hate for train travel. It is thought that his travelling companions were Ellen Ternan and her mother, though this is not documented by Forster in Dickens’ biography.

In the postscript to Our Mutual Friend, Charles gives a brief reference to the incident, but does not mention the names of his companions, even though he refers by name to four other passengers whom he helped. Dickens’ rescue work was surprisingly not referred to in the lay press given that he was such a famous person by then. Subsequent researchers surmise that he deliberately suppressed the details of the incident to conceal his infidelity.

Writings on Ceylon

The writings which refer to Ceylon, under his name, fall into two categories – in his novels and in journal articles.

Dickens makes reference to Ceylon in two of his novels. The first was in Great Expectations published in 1861. In this book, which is only one of the two books he wrote in the first person (the other being David Copperfield), Dickens puts these words into the mouth of the budding entrepreneur. Henry Pocket:

‘“I think I shall trade, also,” said he, putting his thumbs in his waist-coat pockets, “to the West Indies, for sugar, tobacco, and rum. Also to Ceylon, especially for elephants’ tusks.”’

The other novel in which Dickens mentions Ceylon is The Mystery of Edwin Drood, the last book he wrote before his death in 1870. Here he puts the following words into the mouth of Neville Landless, the orphan twin:

‘“To be my guardian? I’ll tell you, sir. I suppose you know that we come (my sister and I) from Ceylon?”’

The writings on Ceylon in journals are all published in either Household Words or All the Year Round. I was able to track down seventeen articles in the former and eleven in the latter:

In Household Words:

- A Cinnamon Garden

- The Cocoa-Nut Palm

- Peep at the “Perahara”

- The Art of Catching Elephants

- My Pearl Fishing Expedition

- Coffee Planting in Ceylon

- Shots in the Jungle

- Garden of Nutmeg Trees

- A Dutch Family Picture

- An Ascent of Adam’s Peak

- An Indian Wedding

- The Buried City of Ceylon

- Law in the East

- The Garden of Flowers

- 15. A Pull at the Pagoda Tree

- Number Forty-Two

- Rice

In All The Year Round:

- Full of Life

- Trifles from Ceylon

- Three Simple Men of the East

- More Trifles from Ceylon

- More Trifles from Ceylon

- More Trifles from Ceylon

- More Trifles from Ceylon

- More Trifles from Ceylon

- Shots at Elephants

- Going to Law in Ceylon

- Openings in Ceylon

Evidence of a visit to Ceylon

The first mention of Ceylon in his novels was 23 years after his first book, The Pickwick Papers, was published. Dickens’ biography written by his close friend, John Forster, shortly after Dickens’ death, shows no evidence of a visit to Ceylon before 1860. He was too busy publishing books and a journal, moving from house to house and travelling to Europe. There is no evidence of a visit between 1860 and 1870, when he visited Paris and North America. In 1861 he considered travelling to Australia with his daughter, but never did. Even though his second son, Walter, died in 1864 while serving in the British Army in Calcutta, there is no evidence of his attending the funeral in India. In fact, Dickens never visited the East. There is some evidence from his writings that he did not have a good opinion of Indians, probably stemming from the Indian Mutiny which had just been suppressed in 1859.

Both journals in which the articles on Ceylon were published were weekly journals which carried the phrase “Conducted by Charles Dickens” on the title page and each pair of double pages within. Though articles on Ceylon in both journals were written in the first person, it is apparent that they were not written by Dickens. However, no acknowledgement is given by Dickens to their authors anywhere in the journal. This then raises the intriguing possibility that Dickens was guilty of plagiarism.

Plagiarism is defined as letting someone else write a paper for you, paying someone else to write a paper for you, or submitting as your own someone else’s unpublished work, either with or without permission. Thus, according to current laws, Dickens was committing plagiarism, as names of all authors (except of a few famous writers whose names appear only in the Index) do not appear anywhere in the journals. Interestingly, Dickens in a statement at the end of one journal article, absolves himself from any opinions expressed in the article. Lai2 states:

“Anonymity was to be a distinguishing feature of Dickens’s journals from their inception, and … a common enough feature of Victorian print culture at this time”.

Yet Dickens waged a relentless war against plagiarism of his work in America.

Actual authors

Who, then, were the actual authors of the articles on Ceylon in the two journals?

The Office Book was a record kept by the sub-editor of Household Words, Wills Lohrli3 identified authors for all articles but one on Ceylon in Household Words from the Office Book. It became clear from her studies that “Sunshine on Daily Paths” was an anthology of articles from Household Words published in 1854 by Peck & Bliss, Philadelphia, without identifying authors, a common practice among American publishers at the time.

Three authors identified for seventeen articles in Household Words were John Capper, Augustus Frederick Gore and William Knighton, all of whom held positions in Ceylon during this period.

Of the eleven articles on Ceylon in All The Year Round, only one author, Francis Jeffrey Dickens, has been identified, while one anonymous article, Shots at Elephants, is mostly from the writings of James Emerson Tennent. An Office Set for this journal was apparently sighted at the turn of the 19th century but its whereabouts are unknown4.

John Capper

John Capper was the author of the following articles in Household Words between 1851 and 1855:

- A Cinnamon Garden, 1851

- The Cocoa-Nut Palm, 1851

- My Pearl Fishing Expedition, 1851

- Coffee Planting in Ceylon, 1851

- Peep at the “Peraharra”, 1851.

- Garden of Nutmeg Trees 1851

- The Art of Catching Elephants, 1851

- A Dutch Family Picture, 1852

- An Indian Wedding, 1852

- Law in the East, 1852

- The Garden of Flowers, 1852

- A Pull at the Pagoda Tree, 1853 (with W H Wills)

- Number Forty-Two, 1853

- Rice, 1855

Capper, born in Lambeth, Surrey, in 1814, was a writer and orientalist. He first worked as a journalist, becoming sub-editor of The Mining and Steam Navigation Gazette. He was then employed by Acland and Boyd, a coffee wholesale company in England, and was sent to Ceylon in 1837 to oversee the clearing of native vegetation for new coffee plantations. He married Anna Amelia Acland, daughter of the founder of Acland and Boyd, in St Paul’s Church, Kandy in 1839, from whom he had four children. Anna died and was buried in the Galle Face Cemetery; two of their daughters were also buried there. Part of the famous Green was the first British burial grounds from 1803, until the tombstones were translocated to the General Cemetery, Kanatta in 1877. Capper then married Sarah Anne Richards in1859 in Shoreditch, Middlesex, from whom he had two children.

Capper founded the Ceylon Magazine in 1840, with contributions from scholarly individuals, who formed the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society in 1845. Capper was its first Treasurer and Librarian, while James Emerson Tennent was one of the three Vice Patrons.

With the coffee market collapse in 1847, he returned to London and wrote his articles for Household Words. He seemed to have had a liking for Ceylon as he returned in 1858 and purchased the twice weekly The Ceylon Times, which he edited until 1874, when he sold it and left the island for the second time. He promoted Ceylon tea at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, and in Calcutta in 1853.

In 1865, Capper was instrumental in the creation of the Ceylon League, which agitated against the government over the stringent disbursement of its revenue. He and John Ferguson, of the Ceylon Observer and compiler of the Ceylon Directory, were great rivals.

Capper authored several books on India and Ceylon, amongst which were:

- Pictures from the East, (with illustrations by van Dort), 1854

- The Three Presidencies of India: A History of the Rise and Progress of the British Indian Possessions, 1855

- The Duke of Edinburgh in Ceylon; A Book of Elephant and Elk Sport, 1871

- A Full Account of the Buddhist Controversy, Held at Pantura [Panadura], 1873

- Old Ceylon, Sketches of Ceylon Life in the Olden Time, 1878

Capper returned to the island a third time in 1882, and with two of his sons revived the moribund The Ceylon Times as an evening daily, The Times of Ceylon, which became the island’s leading English newspaper. He wrote a chapter entitled The Dagobas of Anuradhapura in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, documenting the work done by his late son, George, who was an official government surveyor during Gregory’s governorship.

Capper seemed to have mastered the Dickensian style of writing, which may have been the reason that so many of his articles (sixty in all over a seven-year period) were received for publication in Household Words.

Afflicted by paralysis, Capper died at 83 years in Fulham, London in 1898, until which time he was an active member of the Royal Asiatic Society of Ceylon.

Augustus Frederick Gore

The author of one article on Ceylon in Household Words entitled Shots in the Jungle (1851) was Augustus Frederick Gore.

Gore was born in 1826 in Galway, Ireland. He served as acting private secretary to Sir Anthony Oliphant, Chief Justice of Ceylon, who was appointed to the position in 1838 and lived in a property called Alcove in Colpetty, later known as Maha Nuge Gardens. It was sold to Sir Harry Dias Bandaranaike, the first Sinhalese judge of the Supreme Court and a forebear of Felix Dias Bandaranaike. Gore probably continued to serve Christopher Temple in 1850, when Oliphant left Ceylon.

Gore was in Ceylon for only 2 years, from 1850 to 1851. After that he was appointed to the West Indies, where he rose to the rank of Lt-Governor.

His article, Shots in the Jungle, was about a hunting expedition in the north of Ceylon. He commits an error in the opening sentence:

“It was late in the month of June, 1840 that myself and a friend (who had hunted elk on the Newara plains, and shot snipe at Ratnapoora) finding ourselves at its capital, Jaffna, resolved to have a shot at the spotted deer of the Northern Province of Ceylon.”

The problem was that Gore was not in Ceylon in 1840; he was just 14 years old at the time.

On reading the manuscript, Dickens wrote to Gore on July 4, 1851:

“I am happy to retain your sporting adventure for insertion in Household Words. It is very graphic and agreeable and I have read it with pleasure”.

One wonders at the care with which articles were edited for the periodical. Gore died on 21 September 1887 in Ireland at the age of 61 years

William Knighton

Born in Dublin in 1823 as the youngest son of Richard Knighton, William Knighton wrote two articles in Household Words:

- An Ascent of Adam’s Peak, 1852

- The Buried City of Ceylon (with Henry Morley), 1852

Knighton graduated from the University of Glasgow and went to Ceylon in 1843, when 19 years old, as Master of the Normal Seminary in Colombo, a training school for vernacular teachers. Not long after, he was appointed manager of a coffee estate in the Kandy district. Obviously not liking the work he was assigned, he was soon back in Colombo as editor of a newspaper, the Ceylon Herald, amongst whose contributors was James De Alwis, who wrote the Sidath Sangarawa. He seems to have found plenty of time in his new position, as he writes:

“Fortunately, the paper was published but twice a week, so that I had ample time to write leaders and correct the proof sheets, to write letters to myself and answer them in the editorial columns, to note down answers to correspondents in my liveliest vein, and to go through all the other business.”

The newspaper’s printing press was later bought over by The Ceylon Times in 1846.

Knighton stayed in Ceylon for only 4 years, but travelled extensively, even climbing Adam’s Peak. He was the first Secretary of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society; hence he would have known John Capper.

Knighton went to Calcutta in 1847 as lecturer in History and Logic at the Hindu College. While there he compared the systems of education in Bengal and Ceylon at the time:

“I expected to find a similar system, producing similar results, to the one which I had just left in Ceylon. I was lamentably disappointed. … In Ceylon, the religious authorities are keenly alive to the interests of education, and allow nothing to escape their observation and attention…”

In 1847 Knighton had married Louisa Agnes Duhan, distinguished as a poetess and essayist, and had four children, three sons and a daughter. Knighton spent his time in London writing and lecturing in the mid-1850s, while living with his family in Chelsea. Here he developed an acquaintance with Thomas Carlyle, and talked with Mrs Carlyle about the second of his articles, The Buried City of Ceylon.

In 1858, he travelled again to India as Assistant Commissioner in Oudh (Awadh).

The family returned to London in 1868, living in Eastgate House, a boarding school for girls, in Rochester, not far from where Charles Dickens lived.

After his first wife died in 1882, Knighton married Charlotte Augusta Drake, a widow with a major share in Glengallen, a merino wool sheep station in Queensland.

The books authored by Knighton were:

- The History of Ceylon, 1845

- The Private Life of an Eastern King, 1855;

- Tropical Sketches, or Reminiscences of an Indian Journalist (2 Volumes), 1855

- Edgar Bardoni: An Autobiographical Novel, 1856;

- Elihu Jan’s Story, 1865;

- Struggles for Life, 1886.

In 1887 Knighton was elected to the Royal Society of Literature in London and was a member of the London Society of Arts and Vice President of the International Literary and Artistic Association of Paris. He visited Paris with his wife in 1888 and had a bronze statue of Shakespeare erected in front of his window. He donated the statue to the city, but it was not received well by the public. In 1941 the statue was removed and the bronze melted down and used for the war industry.

In 1889 Knighton bought a house called Tileworth at St Leonards-on-Sea, Sussex. He was an active and popular member in the community. He died in Tileworth Lodge on 1st April 1900 at the age of sixty-six and was buried in Woking Cemetery.

Francis Jeffrey Dickens

One article in All The Year Round, entitled Trifles from Ceylon (1863), was written, according to records in the Office Book, by Francis Dickens, the fifth child of Dickens. Written in the first person, it comprises a collection of episodes about harmful animals in Ceylon.

If Charles Dickens did not visit Ceylon, did one of his children?

Francis Dickens, born in 1844, was 19 years old when this article was written. He left for India in 1863 to serve in the Bengal Police until 1871, returning to England only after his father’s death. He may well have visited Ceylon while he was in India, but the article was written in the same year he left for India. It is most unlikely that he was given leave to visit Ceylon either on the way to, or in his first year of, military service. He may have visited Ceylon before then, but the text indicates that the writer had been in Ceylon for some time and was married:

“I have been a good many years in Ceylon, and yet I have only once been bitten by a centipede.”

“My wife one day opened a drawer, and was going to put in her hand …”.

There is no evidence that Francis was ever married or had children. The article was obviously not written by him, but for some reason attributed to him. It is known that he held a minor editorial position in the office of All The Year Round before he left for India in 1863. It is possible that he was paid for his editorial help in publishing this article, and his name was misleadingly inserted in the “Author” column of the Office Book.

The writer of this article, Trifles from Ceylon, remains anonymous, as do the writers of the remaining five articles in the series More Trifles from Ceylon which followed. It is most likely that all six articles were written by the same person, who had lived in Ceylon for a considerable period of time. This is evident from a statement made in the first article of the series:

“I purpose (propose) jotting down from time to time such incidents as I have come across during a lengthened sojourn in Ceylon.”

All articles in the series, dated 1864, concern animal life in Ceylon.:

- More Trifles from Ceylon (alligators)

- More Trifles from Ceylon (many animals)

- More Trifles from Ceylon (elephants)

- More Trifles from Ceylon (snakes)

- More Trifles from Ceylon (fish and crocodiles).

Thus, the authors of all eleven articles on Ceylon in All The Year Round will have to remain anonymous for the present.

Death and Burial

In April 1870, Dickens began serializing his last book, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. He was able to complete only six of the planned 12 instalments as he died of a stroke on 9th June.

He had spent the day alone writing in the Chalet, which was a gift to him in 1864 and erected across Rochester Road from his Gads Hill Place residence. He had a tunnel constructed under the road for easy access, avoiding the danger of crossing Rochester Road. This tunnel still exists. The Chalet, however, was subsequently reassembled in Eastgate House.

Returning to the house late in the afternoon of 9th June, he wrote a few letters before dinner. Georgina had noticed a pained expression on his face. He uttered a few incoherent sentences, stood up unsteadily and was prevented from falling by her and led to a sofa. A local doctor was summoned to attend to him. As he showed no signs of improvement, a telegram was sent to summon John Reynolds, an esteemed London neurologist. In spite of all these efforts, he expired just after 6.00 p.m. His last words were: “On the ground”.

Dickens did not get to complete even the last sentence he ever wrote in his last book, The Mystery of Edwin Drood:

“ ’Or’, pursued Poker, in a kind of despondent rapture, ‘or if I was to deny that I came to this town to see and hear you, sir, what would it avail me? Or if I was to deny -’ ”.

Many attempts have been made by others over the years to complete the novel. There have been at least six publications, four plays and a musical.

Two of the characters in the novel, Neville and Helena Landless, were born and raised in Ceylon by a cruel stepfather after their mother died. They were rescued from their miserable situation and sent to England.

Why did Dickens choose Ceylon and not India, as their country of origin?

A BBC portrayal for Dickens’ 200th birthday, made them Indian not Ceylonese. Hughes, a crime writer, decided for no reason that the twins were from a British father and Tamil mother. It was not unusual at the time for the British in tea plantations to have illicit affairs with South Indian women working on the plantations. Michael Roberts5 wrote:

“Such liaisons were not uncommon, especially on lonely hill country estates. Because they were taboo and frowned upon by other Europeans, they were carried on surreptitiously, and the women and the resulting children were not always acknowledged.”

Lillian Nayder6 believes that Dickens’ used Ceylon, not India, as:

“Ceylon was a colony in which the harsh treatment of natives had long been accepted as a necessary feature of the British administration, since the Kandyans were represented as an unusually troublesome race, in a continual state of insurrection”.

Tennent7, a friend of Dickens, referring to the Kandyan wars wrote:

“Ceylon was a land where the need for martial law, and the desire for “vengeance” and “retribution” on the part of the British appeared self-evident”,

According to Forster8, Dickens’ preferred place of burial was:

“in the small graveyard under Rochester Castle wall, or in the little churches of Cobham or Shorne, …”

Though Forster states that these graveyards were “found to be closed”, a recent study of the church records at Cobham and Shore showed that this was not so. A grave was even dug in St Mary’s Chapel at Rochester Cathedral, but Forster and the Dean of Westminster, encouraged by the Press, were keen on burying Charles in the Abbey, while Georgina and the neighbours preferred otherwise.

He was buried in Poets’ Corner of Westminster Abbey on Tuesday 14 June 1870. Among the mourners was Ellen Ternan. The grave was left open to the public for three days.

Forster writes:

“Facing the grave, and on its left and right, are the monuments of Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Dryden, the three immortals who did most to create and settle the language to which Charles Dickens has given another undying name.”

(This article was first published in THE CEYLANKAN, Vol 26/3, August 2023, as “Charles Dickens on Ceylon”

- 1.

( The writer is a well known anatomist and medical educator and avid collector of books on Ceylon covering the British colonial period)

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.