Minnette’s groundbreaking Kandy housing scheme

At the Watapuluwa site: Minnette de Silva with Chinese parasol et al

The Watapuluwa Housing Scheme in Kandy is an example of how in many ways Ceylon fared so much better than the Sri Lanka it was to become. Built by the first Sri Lankan woman architect Minnette de Silva, the scheme was unusual in that each house had a generous 40-perch plot (altogether the scheme extended 88 acres) and was in that revolutionary style of hers, epitomised by the mingling of modernism and traditional Sinhalese vernacular.

Not all, alas, have survived of that original scheme finished in 1958 but its pristine imprint will not fade away, thanks to the new exhibition at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), which has decided to shine the light on this, the first social housing scheme in Ceylon and ergo, Minnette’s somewhat overlooked contribution.

It was the heady days after Independence in the ’50s and the government, with the new housing minister, Sir Kanthiah Vaithianathan, had realized the need for a ‘democracy of house-owners’. Meant for civil servants, the land bought for the scheme was adjacent to the Ceylon Tobacco Company premises.

Young Minnette did not ‘adopt the most pragmatic approach’ when it came to designing Watapuluwa, says Sharmini Pereira, chief curator of MMCA, with a wry smile, because the thirty-something architect enthusiastically waded in, distributing a long questionnaire to each civil servant who was to occupy her finished Shangri-La (for such it was to be and would become – with multi ethnic and religious harmony) – with such specific questions as whether they wanted a servant’s room or what was the wall to be built of.

Practical it may not have been, but this was architecture decades ahead of its time; participatory and taking into account the site as well as the users’ needs.

Practical it may not have been, but this was architecture decades ahead of its time; participatory and taking into account the site as well as the users’ needs.

This must have then seemed quixotic, when the ‘commonsense’ solution was to put up prefabricated or modular units, and an engineer usually at the helm with no architect at all.

Thus in many ways Minnette was a trailblazer and her writing (she was a good if occasional scribbler) is peppered with words like ‘regional’ and ‘climate’ and ‘local artefacts’. In the fifties ideas such as regionalism, including use of the crafts of the region, were some two decades precocious.

The houses were split level and Minnette envisaged them to be flexible: the car porch for instance could also be a verandah, and a place for the children to play.

But of course not everyone was ready to accept the tastes – of even a RIBA-qualified architect and daughter of suffragette and society woman Agnes Nell and George E. de Silva, sister of art historian and author Mercia de Silva (Anil de Silva-Vigier as she was to become) – all arbiters of style.

Many of the houses were altered by occupants, and parts of land sold (Minnette, however, remaining mostly undismayed with remarkable adaptability strange in her generation).

Sharmini Pereira

Minnette, who travelled a lot with her father (a minster in the government) apart from her formative years in India and England, absorbed everything she saw, and particular influences for Watapuluwa, says Sharmini, were Otto Königsberger, the urban development pioneer with whom she worked in India, and Patrick Geddes, whose book endorsing thinking about the participants or the uses of any scheme she admired.

Concentrating on just one Minnette project in a ‘huge amount of detail’, the curators at MMCA Sharmini, Ritchell Marcelline and Thinal Sajeewa hope to do greater justice to the pioneering woman architect, better recalled – even now- for her silk sarees, Chinese parasols and flowers in her hair (or, in later age her slender form wrapped in silk shawls) or her association with master architect le Corbusier.

Sharmini hopes the exhibition will encourage others and themselves look at Minnette ‘project by project’ in more depth, so eventually, “we can compare and contrast works which might lead to a survey show of her works.”

Says Sharmini, “The exhibition also brings together the many aspects of Minnette- the architect, the writer, the teacher… but also recognizes her as a thinker in terms of some of the things she was advocating for: her lobbying for thinking of our region, the here and the now, the climate, types of topography, ‘don’t look at the international just because of its style, style is not something you can cut and paste’, and (that) we should look at something from the ground upwards…”

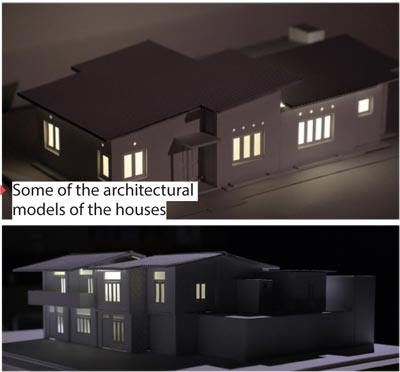

The exhibition itself has been endorsed by the World Monuments Fund. Assistant curator Thinal Sajeewa adds that, while finding original drawings and models was a problem, “the works on display include sound material, commissioned drawings, architectural models, and video to help the audience better understand the scheme and De Silva’s practice.”

“The exhibition is a must see for all those who are interested in or simply curious about architecture and Minnette De Silva.”

The exhibition, titled ‘88 Acres: The Watapuluwa Housing Scheme by Minnette De Silva’, will be on at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art at Crescat Boulevard from November 30 till July 7, 2024 from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

| She paved the way to tropical modernism | |

| Minnette de Silva was a rara avis for that period of Ceylonese history and was a sensation at the Bombay School where she was the only woman student. She studied at the Kandy Convent, Bishop’s College and St. Mary’s Brighton, and studied architecture at two Bombay institutions- a private academy run by G.B. Mhatres and the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy School of Art. It was a chance meeting with Ceylon’s Governor the Viscount Soulbury that led her to be an associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects – the first Asian woman to have that honour. Returning to Kandy in 1949 Minnette set up practice, away from Colombo but at the heart of traditional Lanka- the home of lacquer work, Dumbara mats and religious and feudal architecture. Before Watapuluwa she had designed three low cost houses, and was to go on to do such landmark buildings like the Coomaraswamy twin houses in Albert Crescent, much admired by Geoffrey Bawa. It was she in fact who paved the way to tropical modernism. She travelled, wrote and lectured on architecture based in London and Hong Kong, but was drawn unerringly to our hill capital. Her practice floundered around the same time Bawa was emerging. Minnette died penniless in hospital in 1998 after falling from her bathtub in Kandy and having not been found for days.

|

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.