COP28 and the garden city irony

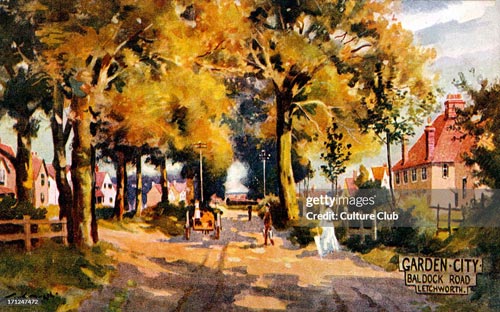

The world’s first Garden City. Pic courtesy Getty Images

Climate justice is the future. The responsibility and the future of nature positive cities featured in COP28. In a first time quantification of historical emissions by the UK based Carbon Brief, Britain holds responsibility for almost twice as much global heating as previously thought when its colonial history across 46 former colonies particularly India, Myanmar and Nigeria is taken into account.

The Netherlands accounts for three times as much warming when accounting for colonial emissions particularly in Indonesia under Dutch rule. This quantification comes to COP28 in the same week the Dutch and Sri Lankan governments celebrate the return of historical objects looted from Sri Lanka.

Rising global temperatures cause sea levels to rise and increase extreme weather events such as floods, droughts and tropical diseases. Added to this, the rapid expansion of cities exacerbates public health issues. Urban pollution is a prime contributor to respiratory diseases and mental health challenges.

Blueprints for the 1920s

Wide open spaces and greenery for all sections of society in colonies was not a part of city planning of the 1920s when Colombo was presented with its first town plan. However, the idea did reach the long colonized Colombo through planner-dreamers and utopians in the same period. It was the time of the Industrial Revolution and the Spanish Flu which impacted up to a third of the world’s population and took the lives of 20-50 million young lives between the ages 20-40. By 1920 Ceylon had lost 6.7% of its people to the Spanish flu (the largest loss of life in one year in the island), and soon after, a malarial epidemic in the 1930s swept the island, snatching away 1.5% of the population in just 7 months.

Dreamscape

It was in 1903 that Ebenezer Howard, envisioned a concept of a Garden City for all social classes which he built in Letchworth, England. The concept moved from Europe to West Africa, South America, and Asia, when cities worldwide were transforming into zones of quarantine, disease control and death management.

The idea travelled the world over and saw its adaptation in several often violent and exclusionary forms along British and French colonies of the period. Within the same decade – in the first of the Soviet Union’s five year plans, Joseph Stalin saw to the planning of the world’s first completely planned city, a socialist utopia in Magnitogorsk. Russia’s steel city was built along rigid lines of production in stark contrast to the Garden City idea.

Known for his distaste of grids, rigid lines and humans in horse stable like housing, the Garden City idea was brought to Colombo by Patrick Geddes. This Scottish Orientalist and planner was influenced by Mahatma Gandhi and left an impression on the tropical modernist architectural movement of Ceylon particularly the philosophy and architectural style of Minnette De Silva.

By 1921, the first formal town plan for Colombo presented a blueprint for Colombo as a Garden City. It would stretch from Colombo Port all the way south toward Galle. It was a utopia for a tropical garden haven. Governor Manning promptly dismissed the plan as expensive and unnecessary. The idea inspired by science fiction, socialism and practical solutions was to morph Colombo into a Garden City, a haven of health. It was a response to the stifling grip of carboniferous capitalism of the 1920s and promised Colombo a breath of fresh air, both literally and metaphorically.

The blueprint presented a green canvas of streets lined with avenue trees, traditional Ceylonese home gardens, and open spaces adorned with aquariums and parks along with a culture of horizontal living, wellness and citizens’ house pride. It was a blending the metaphor of the town with the metaphor of the village from an Orientalist lens. Unlike romanticised images of Old Colombo suggest, a history of Colombo as described by Municipal sources of the period presents a different picture. Colombo in the 1920s was a city marked by a series of sanitation crises and floods, and the Garden City plan offered an alternate reality.

The suggested plan (or dream) was that a tourist’s journey unfolds through a verdant Colombo, beginning at the Galle Face aquarium to meander through flower-lined boulevards of Colpetty and Duplication, to be greeted by the panoramic view of the Indian Ocean and fresh breeze at a wide open beach space at a seaside park and zoological garden in Wellawatte. The return trip along Bambalapitiya Road, past the Racecourse, through refreshed Torrington Parkways to Victoria Park, ends at Colombo National Museum’s botanical haven. It was a vivid planner’s dream in Asia, contrasting sharply with the bazaars of Bombay.

Gardens hold different significance and meaning to people across time, context and language. Sri Lanka holds an ancient heritage of various forms of gardens across the island.

Fragments of the concept of the garden city still linger in the chemistry of Colombo today in a Sri Lankan context in 2023. It emerges at some points and recedes at others. This is due to the haphazard adoption of formal plans for Colombo as a garden city from the 1920s and 1940s and why the city developed largely without reference to a plan until after World War II in the mid-1940s. It is why varied vintage and modern buildings still exist side by side, and housing for under-served income groups and crowded commercial bazaars are not far from exclusive residential areas. This is contemporary Colombo, and its ethnic and socio-economic mix through streets wide and narrow is to be celebrated.

One of the failures of the early Garden City movement was that it could not remain affordable to blue-collar workers, a challenge of relevance a century later.

The design of the Garden City presented a subtle yet profound form of political and social stewardship and control. It is a testament to a bygone era’s colonial legacy intertwined with the city’s fabric for it aimed at more than just aesthetic appeal or health; it was about cultivating a sense of communal pride and a well-knit society, vital in a time when colonial Ceylon was stirring with political consciousness in the beginnings of a movement for independence. The Garden City vision was about nurturing a populace that wasn’t just healthier but happier. It presented ideas for cleaner breathing, but was also a systematic form of social control.

This idea in Colombo was never adopted by the Colombo Municipal Council which was on the verge of bankruptcy in the ’20s – the concept has been shrouded in ambiguity and rejection for a century. However, the sustainability solutions offered by Garden City Movement are already being imagined the world over.

The future

The Garden City Movement in its contemporary 2023 form is gaining currency globally,particularly in a post pandemic context. Ebenezer Howard’s utopia Colombo still bears much potential to be reimagined as a garden haven for clean breathing in an inclusive and accessible form.

The Garden City of the East should move from intent to impact.

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.